The Phantom Superfight: When Antonio Inoki Almost Danced with the Devil

A Fever Dream of the World's Wildest Promoter

Pull up a chair. This ain't your typical box score rundown or interview aggregation, folks. This is the story of a fight that never was, featuring a dictator, a wrestling god, and a promoter who’d try to sell you the Brooklyn Bridge if he thought there was a headline in it.

The Phantom Superfight: When Antonio Inoki Almost Danced with the Devil

You think you’ve seen crazy in the wild world of sports? Tyson biting Holyfield? The Malice at the Palace? Bill Belichick being led around by the nose by a girl young enough to be his granddaughter?

Child’s play.

Picture this: January 1979, Tokyo. A press conference at the lovely Keio Plaza Hotel that sounds like the setup for a fever dream. On one side, Antonio Inoki, Japan’s wrestling deity, the man with the "Burning Fighting Spirit." On the other, the invisible, hulking presence of Idi Amin Dada, President of Uganda, a man whose resume included titles like "Black Hitler" and the charmingly understated "Man-Eating President."

Okay, so Amin didn’t actually show up for the press conference. But he was there in spirit. More importantly, his name got the announcement carried in the Asahi Shimbun and Yomiuri Shimbun as well as on wire services reaching from Taiwan to Timbuktu. This wasn’t just an announcement for the wrestling magazines.

This was a happening.

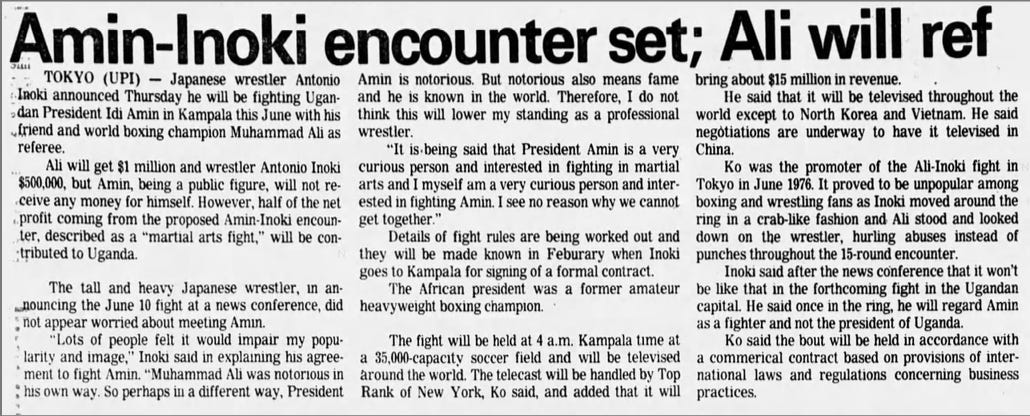

And the fight? Oh, it was going to be a fight. June 10th, Kampala, Uganda. 35,000 screaming fans in a soccer stadium at the crack of dawn – 4 a.m. local, just so Japan and the U.S. could catch it at times convenient for terrestrial TV. The man pulling the strings, the puppet master with the wild eyes? A character named Yoshio Kō, an "International Dark Producer"and a self-proclaimed dealer in dreams and schemes, plots so outlandish they made P.T. Barnum look like an accountant – who decided Amin was the "perfect target."

Kō had already dipped his toes in the Ali-Inoki waters in '76, an advisory gig for that memorable clash. But this? This was Kō’s style, cranked to eleven.

He’d flown to Uganda, gotten the red-carpet treatment, and sat down with Amin himself for dinner. The food was “indescribably awful. The potatoes and corn were inedible. The meat also had a strange taste.” But the conversation flowed easily. He described the dictator as exuding "an indescribable, mysterious demonic power," a "wildness, a unique, animalistic barbarity." Amin, a former East African boxing champ, apparently signed on the dotted line, maybe seeing a payday for his crumbling nation, maybe just digging the sheer audacity of it all.

And the cherry on this bizarre sundae? Muhammad Ali, "The Greatest," was slated to be the referee. Inoki, for his part, was all in. He needed to wash away the stink of the Ali fight, restore his honor, and this? This was bigger than Ali. According to the boxer’s advisor Hisashi Shinma, it was Ali who suggested Inoki for the bout, cleverly countering with the wrestler’s name when the dictator suggested he’d like a boxing match with the champ himself.

“Anyone with a normal sense wouldn't get involved in such an outlandish story,” Inoki wrote in one of his several autobiographies. “However, I feel a sense of romance in achieving unconventional, out-of-the-ordinary things. And the bigger the scale of the story, the more my fighting spirit ignites. ‘This should be even bigger news than the Ali fight.’ Thinking that, I readily accepted Mr. Kō's proposal.”

The money? Astronomical for the time. A $15 million net profit projected. Ali to pocket a cool million, Inoki half that. Amin, as a head of state, wouldn’t get a dime personally; an estimated 1.5 billion yen (that’s with a ‘b’) was pledged to Uganda’s treasury, half the event’s proceeds. NBC was supposedly ready to beam it worldwide with Top Rank running the boots on the ground production.

Of course, there was a slight hiccup. At the same time Kō and Inoki were spinning this yarn in Tokyo, Uganda’s ambassador to Japan, Samsoni Bigombe, was calling it "a complete fabrication" that "tends to demean the highest office". But hey, when did a little thing like an official denial ever stop a good story, especially one Kō was peddling?

The Challenger: Antonio Inoki – More Than Just a Wrestler

So, who was this Antonio Inoki, the man willing to step into a ring, or at least a stadium, with a guy whose fridge allegedly held more than leftover chicken? Born Kanji Inoki, he was a force of nature, a cultural icon in Japan who took pro wrestling and tried to drag it, kicking and screaming, towards something resembling legitimate combat. He was also, as reporter David Bixenspan explained at Deadspin, a bit of a lunatic:

As a mainstream athlete, Antonio Inoki is probably best known for battling Muhammad Ali to a draw in an actual on-the-level fight—albeit one restricted by last-minute rule changes—after The Greatest backed out of plans to lose a traditional entertainment wrestling match. But Antonio Inoki is not a mainstream athlete. He’s a professional wrestling legend, and one of the most grandiose and ambitious batshit merchants that this deliriously batshit sport has ever seen.

Scouted in Brazil by the legendary Rikidozan, the godfather of Japanese wrestling, Inoki was brought back to Japan and molded into a star. He teamed with Giant Baba, a legitimate colossus, forming the "BI Cannon" tag team that dominated the Japan Pro Wrestling scene and took on all the top stars of the day. But Inoki, ever the maverick, got tired of playing second fiddle. He was ambitious, a revolutionary in spandex.

In 1972, he did the unthinkable: he founded New Japan Pro-Wrestling (NJPW), a rival to the established order. This wasn’t just a business move; it was a statement. NJPW became the house of "strong style," a harder-hitting, more realistic brand of wrestling that was pure Inoki. His mantra was "Tōkon" – Fighting Spirit. And "Moeru Tōkon" – Burning Fighting Spirit – became his calling card, a fire that burned in his eyes and in the hearts of his legions of fans.

But Inoki faced a considerable battle against Baba, not in the ring, but as heads of two rival promotions. Baba had the support of wrestling’s institutional powers worldwide and access to the top foreign talent. He presented traditional wrestling in the American style. And he was good at it. To compete, Inoki needed to change the game This led to his infamous "different style fights." The biggest, of course, was against Muhammad Ali in 1976. A bizarre spectacle it was, with Inoki on his back kicking at Ali's legs for 15 rounds to a chorus of boos and cries of "farce!". Yet, in hindsight, that dull fight is now seen as a cornerstone of mixed martial arts. It put Inoki on the global map, even if it nearly bankrupted NJPW. He fought judokas like Willem Ruska, boxers like Chuck Wepner, karate men like Willie Williams – anyone to prove his point. This was a guy who lived for the happening, the surprise, the sheer, unadulterated audacity of it all.

Later, he’d take that same fighting spirit into the Japanese Diet, becoming a politician who practiced "Fighting Spirit Diplomacy," meeting with figures like Fidel Castro and trying to broker peace in places like Iraq and North Korea. He was a showman, a warrior, an enigma, right up until his grand retirement in 1998, with Ali himself passing the torch in a sold-out Tokyo Dome.

"An event of this magnitude is a chance to make pro wrestling known to people all over the world,” he told the press. “My opponent is a villain, but there has never been such an eccentric president before. From what I've heard, besides boxing, he has apparently also mastered judo and karate. As for me, once I step into the ring, I have no intention of holding back."

The Dictator: Idi Amin – The Butcher with a Boxing Past

And his dance partner in this phantom fight? Idi Amin Dada. The name alone sends shivers down your spine. "The Butcher of Uganda," they called him, and it wasn't for his skills with a side of beef. His eight-year reign, from 1971 to 1979, was a symphony of horror – abductions, torture, murder on a scale that still chills the blood. Estimates run from 100,000 to half a million souls extinguished under his watch.

But before Amin was a monster, he was a man. A soldier, Amin clawed his way up from humble, disputed origins, joining the British King's African Rifles. Big, strong, athletic – he was Uganda’s light-heavyweight boxing champion for nine years, supposedly undefeated. His British officers saw him as loyal, obedient, if "not much grey matter" – a classic colonial underestimation that would come back to bite both them, and Uganda, hard.

He became army chief under Milton Obote, Uganda's first president. But alliances in that part of the world, in those times, were as stable as a house of cards in a hurricane. On January 25, 1971, with Obote out of the country, Amin made his move.

Coup d'état.

Initially, some cheered. The West, even. But the honeymoon was brutally short.

Amin’s Uganda became a charnel house. He purged rivals, real and imagined. In 1972, he expelled the country's Asian population, tens of thousands of them, seizing their businesses and homes, a move that shattered the Ugandan economy. He was erratic, a showman of the grotesque, bestowing upon himself titles like "His Excellency, President for Life, Field Marshal Al Hadji Doctor Idi Amin Dada, VC, DSO, MC, Lord of All the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Seas and Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in General and Uganda in Particular."

Try fitting that on a business card.

“More than forty years after his overthrow and eighteen years after his death, he remains a key point of reference in Ugandan culture and politics,” his biographer Mark Leopold wrote. “Elsewhere in the world, his name has become synonymous with brutal and psychotic African dictatorship. In the Western popular imagination, he is a mainstay of books and TV series with titles like The Fifty Most Evil Men and Women in History, The World’s Most Evil People, The World’s Most Evil Dictators, or simply Monsters.”

He played footsie with terrorists, most famously allowing the PLO to land a hijacked Air France jet at Entebbe in 1976, only to be humiliated by the daring Israeli rescue mission that followed. He became an international pariah, a symbol of African dictatorship at its most depraved. Some contemporary reports by insiders like Henry Kyemba suggested he delved in blood rites and even the most horrible of all atrocities, the consumption of human flesh:

To understand Amin’s reign of terror it is necessary to realize that he is not an ordinary political tyrant. He does more than murder those whom he considers his enemies: he also subjects them to barbarisms even after they are dead. These barbarisms are well attested. It is common knowledge in the Ugandan medical profession that many of the bodies dumped in hospital mortuaries are terribly mutilated, with livers, noses, lips, genitals or eyes missing. Amin’s killers do this on his specific instructions; the mutilations follow a well-defined pattern. . . .

There is of course no evidence for what he does in private, but it is universally believed in Uganda that he engages in blood rituals. Hardly any Ugandan doubts that Amin has, quite literally, a taste for blood.

Yet, for all the caricature and exaggeration, much of it encouraged by the dictator himself who enjoyed his reputation as an extremist (once saying “I don’t like human flesh; it’s too salty for me.”) the man held onto power for eight long, bloody years. There was a cunning there, a ruthlessness that many, to their fatal cost, failed to see until it was too late.

The Mastermind: Yoshio Kō – The Impresario of the Impossible

So, who dreams up a fight between a beloved wrestler and a reviled dictator? Enter Yoshio Kō, the "International Dark Producer," the "Man of Emptiness and Charisma," the "kyogyōka". This wasn't a guy selling widgets; he was selling thunder and lightning, smoke and mirrors. His business card just said "Producer," but that was like calling a hurricane a stiff breeze.

“I, Yoshio Kō, a man of mixed blood born to a Chinese father and a Japanese mother, have lived by marshalling all my knowledge and power, spinning strategies, sometimes telling outrageous lies, deceiving and probing the true intentions of tough negotiators from around the world,” he wrote in his wild autobiography. “...There is only one Yoshio Kō in the entire world. For me, life itself is my work, my business, and my creation. That's why I wasn't influenced by anyone, and no one can imitate me.”

Kō’s philosophy was simple: "Life is art". His job? To "kill boredom," to create happenings that danced on the "boundary between fiction and reality." Profit was secondary; the thrill, the spectacle, the sheer audacity of pulling off the un-pull-off-able – that was Kō’s oxygen.

And his resume? A highlight reel of the bizarre and the brilliant:

He tried to bring the Indianapolis 500 to Japan in 1966. Lost a million bucks but, hey, what a story!

He orchestrated Tom Jones's first Japan tour in 1973. Booked him in the Budokan, a venue usually reserved for more… dignified… events. Jacked ticket prices to the stratosphere – 20,000 yen when a monthly salary was maybe 70,000. Sent invites to the Imperial family and the Prime Minister. The established promoters tried to torpedo him, spreading rumors, pressuring TV stations. Kō just grinned and watched the tickets sell out, scalpers making a killing. That, he’d say, was "kyogyōka myōri" – the unique joy of the ephemeral venture.

He launched the "Loch Ness Monster International Expedition Team" in 1973, led by politician Shintaro Ishihara. Recruited team members through newspaper ads, promising "romance and adventure.” Did they find Nessie? Nah. But Kō declared, "We didn't find Nessie, but we found a great romance within ourselves." NBC had apparently offered 1.8 billion yen for broadcast rights if they had snagged the beast.

Then there was Oliver the "Ape-Man" in 1976. A chimp, or maybe not? Oliver walked upright, supposedly had 47 chromosomes (humans 46, apes 48). Kō fanned the flames of the "human or ape?" debate into a media inferno. TV ratings went through the roof. A young Terry Ito, future TV guru, was Oliver’s caretaker, later saying Kō’s ideas were "truly amazing." Things got really weird when a woman declared she wanted to have Oliver’s baby, and Oliver reportedly got aroused by a nude photo. Police stepped in before any bestiality could be televised. Kō just shrugged: "No matter how much the prestigious Asahi Shimbun writes that he's 'just an ape,' people are intrigued... perhaps they want it to be so." That was all show business was at its heart, Kō figured – a monkey show, essentially.

Kō wasn't just a promoter; he was a cultural alchemist, a storyteller who knew that the suggestion of the impossible was often more potent than reality. The Inoki-Amin fight was to be his masterpiece.

The Dream Crumbles: Amin's Curtain Call

But even Kō’s wildest dreams couldn't withstand the harsh glare of reality. As 1979 dawned, Idi Amin’s Uganda was a powder keg with a short fuse. His ill-advised invasion of Tanzania’s Kagera Salient in October 1978 had backfired spectacularly. By January 1979, Tanzanian troops, alongside Ugandan exiles, were pushing back, and hard.

The ink was barely dry on the Inoki-Amin press announcements when Uganda was officially in a state of war with Tanzania, quickly spiraling into a civil conflict. The planned joint press conference in Kampala with Inoki, Amin, and Ali? Cancelled. The fight itself? A ghost before it even had a chance to breathe.

By April 11, 1979, Kampala had fallen. Amin, the "Conqueror of the British Empire," was on the run. The phantom fight of the century had been KO’d by a very real war.

Kō called it "the most regrettable project of my entire career.”

“The situation in Uganda deteriorated rapidly,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Though I had a signed contract and initial agreements, the planned press conference in Kampala with Inoki and Ali had to be called off. Amin's regime was crumbling…Once Amin was driven from the country, there was no longer any way to drag him into a ring. It was regrettable, but I had no choice but to give up. Ali and Inoki, whom I informed of the cancellation by phone, were also extremely disappointed. The NBC staff were also very frustrated. Nevertheless, NBC paid me 5 million yen to cover the wrap-up expenses. Japan, America, Africa – it was a phantom fight of the century that transcended countries, races, and religions. Now, K-1, PRIDE, and other events have made mixed martial arts a popular sport in Japan, with people of all ages getting excited about the intense fights, but this plan was truly its prototype. If it had materialized, there's no doubt it would have become a historic (or notorious) match.”

Inoki, too, was gutted, believing it "would have caused a massive global sensation.”

Looking back, though, Inoki probably dodged a bullet, or worse. He later admitted, recalling Kō’s tales of Amin’s alleged collection of human heads, "I was lucky not to have been added to Amin's collection."

From Dictators to Tigers: Kō's Next Wild Ride

Did the Inoki-Amin implosion slow Yoshio Kō down? Please. This was a man who probably saw a setback as just a dramatic pause. His mind, ever fertile, conjured an even more primal spectacle: a karate master versus a Bengal tiger. A fight to the death, naturally. "A spectacle to surpass even Inoki vs. Amin," Kō mused.

His chosen warrior was Mamoru Yamamoto, a Kyokushin Karate sensei, a former Self-Defense Forces man. Kō popped the question: "How about a real fight, bare hands, against a live tiger?" Yamamoto’s eyes lit up. "Interesting, Mr. Kō. Very interesting." Deal done. Toei Company, the film studio, was already licking its chops, cameras ready.

The venue? Haiti, under the iron fist of Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier. Baby Doc’s government was "surprisingly cooperative," Kō noted, probably smelling tourist dollars or just a bit of international buzz. A circus tiger was flown in, a logistical nightmare involving reinforced cages and agitated roars that had the locals in Port-au-Prince buzzing.

Yamamoto, the karateka, was initially cool. Then he saw the tiger. Really saw it. Its "almost magical agility," its "unimaginable acrobatic suppleness". The blood drained from his face, Kō remembered. The real gut-check came a week before the fight. Two Dobermans, fierce as hell, were turned loose on the leashed tiger. The tiger, looking bored, swatted them. One swat. The Dobermans, Kō wrote, let out a single, high-pitched "Kiiiin!" and went flying, "bright red blood dripped, and skin hung loosely." The tiger’s claws? "Like five deba knives (heavy Japanese kitchen cleavers)."

Yamamoto? He "completely lost everything." Ashen, dazed, he begged Kō: let me use a spear, a knife, chain the tiger, de-claw it, something! Kō was having none of it. A man’s promise, the honor of the strongest karateka, and, oh yeah, the 5 million yen advance Kō had already paid him.

But the world had other ideas. Animal rights groups launched a global firestorm. "Barbaric animal cruelty!" they cried, and the world listened. The US government reportedly threatened Haiti with sanctions. Baby Doc, not wanting the "bad publicity," pulled the plug. The deathmatch was dead.

Kō lost a reported 50 million yen. His reaction? He wasn’t particularly down. "I still think it was interesting," he reflected. "Although an unexpected interference came in, for me, it was a job that felt somewhat like play."

That was Kō. The game was the thing.

The Aftermath: Divergent Paths

And what became of our protagonists?

Antonio Inoki kept that fighting spirit burning. He remained a megastar in NJPW, a legend who transcended wrestling. He took his charisma to the Japanese Diet, trying his hand at "Fighting Spirit Diplomacy," meeting with world leaders, trying to build bridges where others saw only walls. He finally hung up his boots in 1998 in a blaze of glory at the Tokyo Dome against Don Frye, with Muhammad Ali himself there to honor him. A fitting end for a man who always dared to be different.

Idi Amin, the man who once walked Uganda like a blood-soaked colossus, found his end far from home. After fleeing Kampala, he landed in Libya, then Iraq, before Saudi Arabia gave him sanctuary in 1980. He lived out his days in Jeddah, a "manifestly devout ex-monster," as one journalist put it, reportedly receiving a hefty monthly allowance from the Saudis. He dreamed of returning to Uganda, but it was never to be. On August 16, 2003, organ failure claimed him. He died unpunished for his reign of terror.

And Yoshio Kō? The "International Dark Producer" likely just kept looking for the next big, impossible dream. His autobiography is a testament to a life lived on the edge, a whirlwind of schemes and spectacles. He was a dream-weaver, an agitator, a master of mayhem, a man who truly believed that life, in all its messy, unpredictable glory, was the greatest show on Earth.

The Inoki-Amin fight remains one of sport’s great "what ifs," a phantom punch that never landed but still echoes with the sheer, mind-boggling audacity of its conception. In the weird, wonderful, and often terrifying world of high-stakes promotion, Yoshio Kō was the undisputed, undefeated heavyweight champion of them all.

You just can't make this stuff up. Or maybe, if you're Yoshio Kō, you can.

My wife and I stayed at the Keio Plaza on our honeymoon in Tokyo. This story has provided me with a wonderful anecdote for later. What a bizarre article that encapsulates Inoki's eye for the spectacle.

Here for it.