The Night The Glendale Giant Nearly Tamed A Greek God

Jim Londos, Ray Steele and a battle for a $10,000 Belt

Over the weekend I saw a clip from a match that caught my fancy. It was from all the way back in 1932 and featured arguably the biggest wrestling star of all-time, Jim Londos, in a title defense at Wrigley Field.

The mat work here was intriguing, as was the opponent. Ray Steele was a legendary shooter and tough guy who was also known as one of the friendliest, funniest people in the business. What did he look like in a worked match?

We only get a couple of minutes in the clip and it left me wanting so much more, first and foremost information. I wanted to know more about the match. How did it come to be? What did it mean? What was the context?

I had to know.

And now, if you dare, you can find out too! First the clip, then the promised context. Thanks for reading Hybrid Shoot.

January 24, 1931

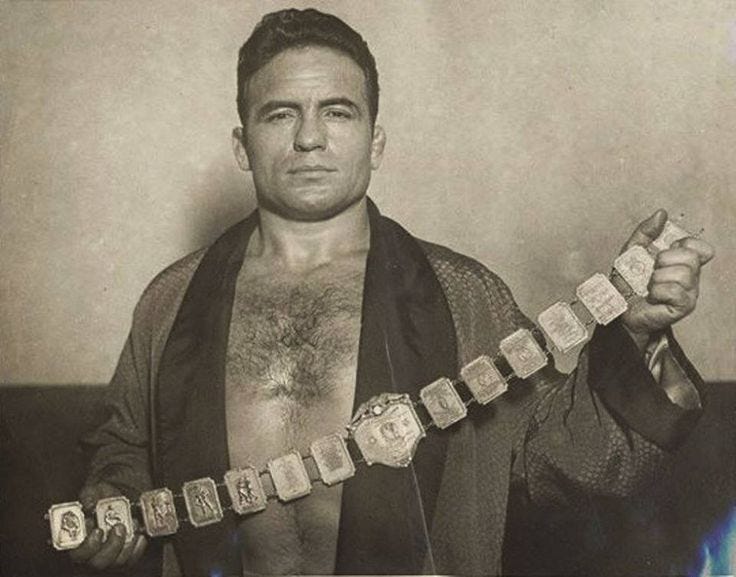

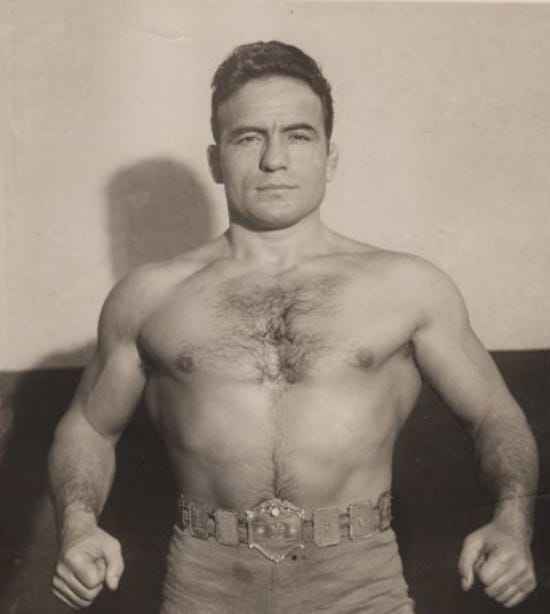

The belt was valued at $10,0001, a small fortune at the time. Fourteen gold-plated medallions, encrusted with diamonds2, tracked the history of the world heavyweight championship, following the chronology of great ones from William Muldoon right up to the present day3 and the man it was bequeathed to at a fancy steak dinner.4

The crust of New York society was there, all wearing comically small straw hats, including the “600 Millionaires” club that had funded the construction of a new Madison Garden a few years before. The magnates dined alongside celebrities like gun-toting Colorado Senator “Wild” Bill Lyons5, tennis star Bill Tilden and retired boxer Jack Dempsey. The highlight of the night, for many, were the lamb chops, so tiny that the gargantuan wrestler “Toots” Mondt did a whole incredulous pantomime bit about their wee-size that brought the house down.6

The belt itself was brought out like just another course, two waiters carrying it on a flag-draped tray.7 For the man of the hour, however, the belt was more than a mere prize or a valuable work of art. It was a symbol, one that gave weight to a claim he was attempting to sell to fans all around the country—that he, Jim Londos, was the best professional wrestler in the world.8

Promoter Jack Curley had taken a big risk bringing wrestling back to the Garden in the early 30’s. Shows headlined by old-timers like Joe Stecher and Lewis had tanked at the box office, drawing just a few thousand fans to the cavernous arena.9 When Curley decided to give it another go, people thought he was crazy.

But he had a secret weapon.

He had Jim Londos.

The first show headlined by the “Golden Greek” drew a supposed 22,000 fans and wrestling in New York was off to the races. It’s no wonder then, that Madison Square Garden stockholders and Curley were so happy to pay tribute to the wrestling king. Curley’s son presented Londos with the belt, and a photo commemorating the evening was sent to papers around the country. Londos was buttering everyone’s bread, providing much needed income as boxing was failing to attract like-sized crowds.

No mere Big Apple sensation, he conquered St. Louis and Chicago in equally grand fashion, then the nation as a whole. Universally popular, Londos drew huge crowds almost everywhere he went, packing 10,000 fans in the Philadelphia Arena for a match with Tiny Roebuck, another 5,000 left out in the cold, heartbroken at missing the show.10 The entire circus, humans and cars lining the streets in a desperate quest for admission, caused a traffic and parking jam that deadlocked the neighborhood.11

“He was the heart of the business as World Heavyweight Champion between 1930 and 1935, and was the catalyst for the largest period of growth wrestling had ever seen,” Tim Hornbaker wrote.12 “His ability as a showman to draw around the country was extraordinary—everyone knew his name and even non-fans were stricken by the urge to see him in person.”

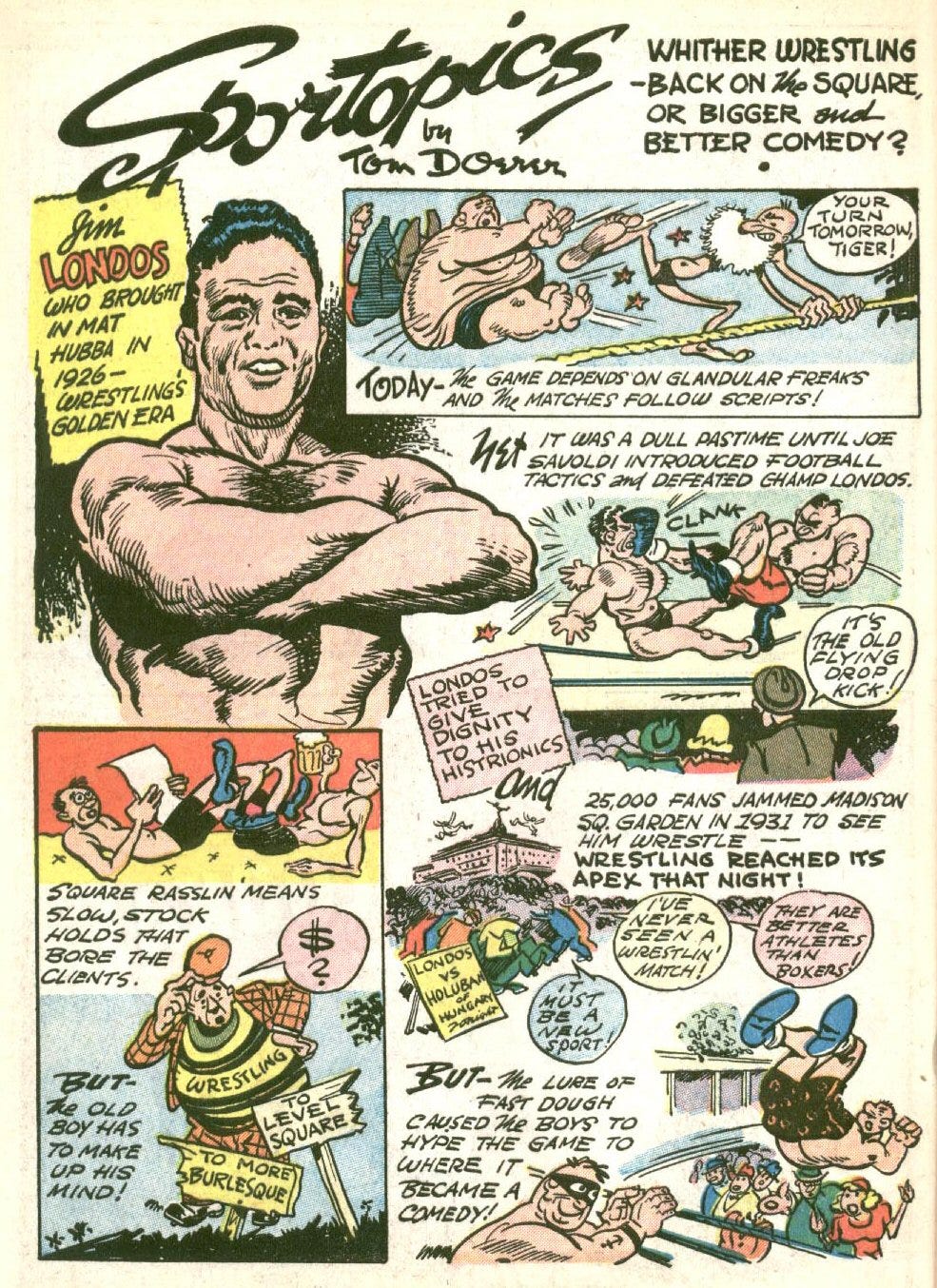

As an entertainer, almost no one would deny, he was a performer like no other. Londos represented an uneasy alliance between two competing ethea, bridging the gap between old school mat wrestlers like Ed Lewis and the action-packed bouts put on by former football players like Gus Sonnenberg, men who didn’t know a wristlock from a wristwatch. Londos had some grappling chops, or at least the ability to successfully pantomime them—but, as historian Scott Beekman wrote13, he was also defining an archetype that reigns in wrestling to this very day, the babyface champion:

Londos provided professional wrestling with its first sex symbol. His matinee good looks drew hordes of female fans to his matches, sold newspapers, and led to lucrative advertising contracts. Curley insured continued positive press for his star by donating the proceeds of several shows a year to Mrs. William Randolph Hearst’s Free Milk Fund for Babies. The promoter’s machinations led sportswriters to spew streams of hyperbole on the ‘‘Adonis of ancient Argos,’’ whose shirtless photos helped sell newspapers.

“I must admit that I have a great fondness for Jim Londos as an athlete and a champion,” celebrity journalist Damon Runyan wrote in his syndicated column. “To begin with, he looks the part, and I like my champions to look the part. No more magnificant specimen than Londos was ever seen in any line of sport.

“He has made a study of his business and his business is showmanship…I do not know how good a wrestler Londos really is. Maybe there are a lot of fellows who can heave him around at will. But I guarantee there isn’t another wrestler who can strike fancier postures and fill the eye better than Londos.”

July, 1932

It was this belt, and the reputation he’d built as an attraction worth seeing, that Londos took with him as California came calling in 1932. He’d toured there in years past before coming East to stake his claim as the sport’s most powerful box office attraction and promoters were keen to have him back.

Not coincidentally, the move corresponded with mounting tensions between partners in New York, believed to be machinated by Mondt, a conniver’s conniver14 who, with Curley basking in his success and paying more attention to promoting dance contests, speed boat races and all-girls boxing, was given free reign to put his own stamp on the wrestling product.15 Just months after presenting him with the expensive token of his appreciation, Curley and the champion were on the outs.16

Believing rumors Londos was looking to start up his own shop, Curley went after him in the press—despite the two still being partners. It was an era of palace intrigue, much of it playing out in the newspapers, and Curley was soon publicly calling for a new champion, insulting Greek fans17, and even partnering with his long-time arch-enemy Strangler Lewis, demanding Londos meet the dangerous shooter in the ring.

“It was like the New York Yankees shoving Babe Ruth out the door,” Londos biographer Johnson wrote, “or New York racetracks padlocking Man o’ War.”

Londos, tired of giving such a large cut of his winnings to promoters18, was more than happy to go his own way. He refused to meet Lewis and was eventually stripped of his championship in New York.19 Soon the men were doing battle, not in the ring, but in the newspapers and behind the scenes, the trash talk flying.20

“He would infer that I am fat and decrepit, broken down and not a fit object on which to clamp headlocks and scissors,” Lewis told the press.21 “If that is true, why doesn’t he meet this tottering old hulk and put him out of the way for all time?”

For all intents and purposes, the two wrestlers simply swapped turfs. Londos took over in California, where Lewis had been headlining, and “the Strangler” essentially took Jim’s gig in New York.

“If you don’t think wrestling is crazy,” one national columnist wrote22, “please remember that Jim Londos is barred in New York because he won’t wrestle Strangler Lewis and Lewis is outlawed in California because he won’t meet Londos.”

The two titans wouldn’t settle their differences until 1934, when they shattered box office records. That’s a story for another day. For our purposes, the failure of Los Angeles promoter Lou Daro to bring the two wrestlers together in July, 1932 left a date open for a big match—a bout Ray Steele was more than happy to take.

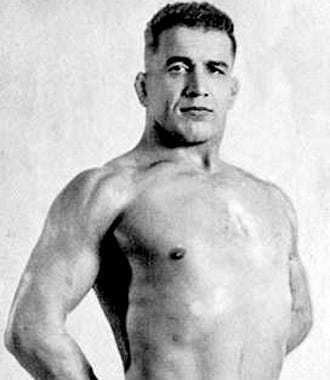

Born Peter Sauer in Norka, Russia, Steele came to America as a mere babe at the turn of the century. Peter’s father had died right in front of his older brother Ludwig before he’d ever truly gotten a chance to know him, his heart failing while pulling water from a well.23 The two brothers went to live with an aunt and uncle and eventually emigrated to Lincoln, Nebraska, where he immediately fit into the local community by becoming the most Nebraskan thing you could be at the time—a wily amateur wrestler. Newspaperman and referee Ed Smith24 called Steele “a product of Nebraska and a most annoying one out of a state that is noted for its great wrestling annoyances.”

He’d trained with Farmer Burns, studied further between the legs of the scissor king Joe Stecher and gone hold-for-hold with Clarence Eklund. He’d even won the World Light Heavyweight title while wrestling under his real name.25 He took on the moniker “Ray Steele” in 1927 and become a leading national name, known for his prowess in the ring and his pranks outside of it.

Steele, according to former NWA champion Lou Thesz26, was “one of the great wrestlers of that era…a handsome, easy-going guy who’d learned his wrestling in the carnivals. He loved women and fun, in that particular order.”

Despite being one of the best legitimate grapplers in the country (or perhaps because of it), he’d settled into a role as Londos’ policeman27, kept on hand to accept the challenge of any tough guys looking to poach the title in the era of the double cross, putting their shoulders to the mat before they could earn a match with the champion.

When it came to employing what they called a “front man” at the time, Londos was far from alone. Gotch had one and so, too, did Strangler Lewis—his name was John Pesek.

“It was Pesek who squelched the opposition when things grew a little embarrassing. Wrestling wars invariably bring challenges and not a little dirt,” columnist Don Roberts explained.28 “Thus, when the enemy moved into Lewis’ territory, it was Pesek who dumped them without further ado.

“Similarly, the front man for the Londos faction has been Ray Steele.”

This setup was, journalist Bill Abbott wrote29, one of the things that distinguished wrestling from, well, everything else in athletics:

In every other sport the best man eventually becomes champion. Wrestling, however, has an adroit system of its own. A colorful personality often wins the right-of-way over an opponent possessing unadulterated mat skill. This strange order of things is strictly for business reasons…Jim Londos was the champion, but the best minds accepted Ray Steele as the premier gladiator in the division.

“Steele is a throwback to the old days,” promoter Curley told Runyon. “…of all the wrestlers of today, Ray Steele comes closest in style and build and his wrestling generally to the man I think was greatest of them all—Frank Gotch…Steele reminds one of the great Iowan in a lot of ways. He is colorful in the same way Gotch was colorful, in his grimness.”

A fantastic and popular performer in his own right, his secondary job was to put the champion over whenever some putting over was required. The two men had wrestled dozens of times around the country, including multiple times in Madison Square Garden. They’d even headlined a card at Yankee Stadium that attracted 30,0000 souls. Steele took the fall that night, as he almost always did. He’d actually won their first match in 1927 by a judge’s decision30, only to fall short in every single bout that followed. As Thesz wrote, the Nebraskan understood his role and was more than happy to put over Londos and others he could beat in a real contest if things were on the up-ad-up.

It was, at the end of the day, just a job:

Ray Steele was the one who explained to me the bottom line in words I’ve never forgotten.

“Kid,” he told me one night over dinner, “you may have the aptitude to become a great wrestler, but if you don’t learn to make money at it...well, then it’s only a hobby.”

Negotiations for the match lasted nearly a month, each move and counter by promoter Daro and Londos’ manager Ed White played out for the press and public. Would Londos have to pay an appearance forfeit? Could he hand pick the referee? Where would he train? Each new term to wrangle over equalled another headline in the newspaper, a brilliant bit of marketing the Londos camp had mastered. Every day brought a new drama to keep things fresh and interesting right up to the opening bell.

With the Olympic Auditorium perhaps fittingly claimed for the upcoming Olympic Games, Daro booked the bout for Wrigley Field, a local landmark built with a distinctive Spanish-style exterior and a nine story clock tower decorating the entrance way.31

The stadium was owned by William Wrigley Jr., the chewing gum mogul who also laid claim to a slightly more famous but equally eponymous ball field in Chicago. Home to the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League (a minor league team, not related to the current MLB Angels), Wrigley had added lights in 1930, making it perfect for a night of wrestling under the clear Los Angeles sky. The ring would be placed right over home plate, making seats behind the backstop and around the dugouts particularly valuable territory.

Taking a page out of boxing’s playbook, Londos and other wrestlers of his stature had begun opening up training camps ahead of a major bout. The champion, for this match, was based out of Ocean Park32, a vibrant beachfront area located in what is now Santa Monica. An easy train ride from the heart of the city, it was particularly popular destination despite the Depression, offering affordable entertainment for struggling families.

Featuring Licks Pier, the area was like a running carnival along the beach, dotted with games, rides, fortune tellers, street vendors and entertainment venues like the La Monica Ballroom, home to thousands of dancers on a busy weekend night. Speakeasies were hidden from the coppers as Prohibition remained the law of the land, but gambling ships that would take patrons out to international waters openly flouted authorities.

The tanned, fit, and muscular, Londos would have fit right in with all the other entertainers and carnies plying their trade, his very appearance a living advertisement for the bout.33

Because of their many matches against each other (and Londos’ winning percentage hovering close to 100 percent), promoters started working the press hard to convince fans Steele had a chance. They played up his credentials as a shooter, spreading a rumor that a promotional war with another Los Angeles faction headed by notorious tough guy John Pesek34 had the Londos regime considering putting it’s title on Steele as a defensive maneuver.

“If so, it will be the first time in rassling history that the ‘policeman’ of one group has been a title holder,” Roberts wrote. “The mat game, of course, has had many such advance guards, who accepted challenges from the opposition when the champ didn’t want to lower himself or was a trifle leery.”

Steele was also said to be perfecting a deadly move called the backdrop “a hold that few grapplers have ever cared to perfect because of the danger of seriously injuring an opponent in slamming him to the mat on his head.” A potential counter for Londos’ sleeper hold, Steele told the press he would look to drop Londos on his noggin as soon as possible to win by knockout.35

Great efforts were made to associate Steele with the matmen of old, the haze of nostalgia obscuring his questionable record against Londos.

“His wrestling ability at the present time,” the Los Angeles Evening Post Record reported, “is said by veterans to be on a par with that of such stars as Frank Gotch, George Hackenschmidt, Tom Jenkins or Joe Stecher.”

Lofty company indeed.

Miraculously, the media blitz seemed to be effective. According to the papers36, the challenger was actually a 10-9 betting favorite two days before the match, ensuring a lively audience that would be paying close attention to even minute swings of momentum. Earlier in the year the other world title had changed hands twice in the city, both times unexpected upsets, making it clear to fans that anything could happen in the City of Angels.37

Being an underdog suited Londos. Small in stature at just a smidgen under 5’8”, he often spent much of the match on the defensive. The psychology of his matches, so common today, was revelatory at the time, his attempts to gain sympathy and make his opponent look strong ground breaking.

“Londos believes that it is effective for a grappler to register the gamut of emotions—rage, misery, compassion, pain, horror, joy,” a journalist explained after interviewing the champion before a match.38 “He believes it is necessary to feign distress at odd moments in order to influence the audience to believe e is near defeat. Then the climax, when he arises from an impossible situation and heaves his opponent into the third row seats. That is good entertainment.”

The day of the bout, 10,000 tickets were released in the grandstand priced at one dollar, augmenting all the reserve tickets that had already been sold at double or triple that rate. Promoter Daro also set aside a special section of the grandstand for athletes in town for the Olympic Games, now less than two weeks away.39 More than 500 were said to have spent a pleasant evening watching the mat men in action.

A rollicking undercard set the stage and, like the smart performer he was, Londos immediately took hold of the crowd.40 A full ten minutes went by before the two locked horns, the crowd growing frustrated with the champion’s hesitance and galvanizing their support behind Steele, billed from nearby Glendale.

“Several of the Olympic athletes present learned something about running after having watched Londos for an hour or so,” Daily News reporter Ned Cronin sneered. “In fact, in his next match the titleholder might even ask that the turns be banked so that he might increase his speed while circling the ring.”

“Londos put on a practice canter,” The Los Angeles Times confirmed, “that made him look like an Olympian in training for the 1500 meters.”

Once the action picked up, however, the wrestlers had a complete grasp on the fan’s emotions. The Pasadena Post called it a “furious match” and described “torrid grappling” that saw Steele take the first fall in just under an hour and a half with a series of reverse headlocks and a head scissors/wristlock to plant Londos on the mat. In the surviving film highlights the ending is not show, only the aftermath—but Londos was dazed on the mat for some time following the Steele victory, making me wonder if he hit his feared backdrop before going to the finish.

Although reported as the first fall Londos had dropped since winning the championship in 1930, it was actually the second. Steele had taken him down for the count at a match in Phoenix as well—but the spirt of the reportage was accurate. Watching Londos lose, even a fall, was a rare sight indeed.

Londos came back with a vengeance in the second stanza, attacking with gusto and weakening Steele with a series of wind-busting body slams before finishing his man off with one of his favorite moves, the airplane spin. The maneuver, arguably the most exciting in wrestling at the time, was described by the New Yorker’s A.J. Liebling as akin to “the climactic movement of an adagio dance or a hammer throw.”41

The third and final fall began with the clock approaching 11 PM and the match itself almost two hours. The crowd, by this point, was all Steele, almost willing the monumental upset. “Steele,” a reporter opined42, “certainly had plenty on the ball last night and the crowd wasn’t bashful about expressing a preference for his chances.”

Instead, time ran out, both on Steele and the bout. Just as things looked like they were going his way again, referee Don McDonald, citing a state athletic commission rule, stopped the contest and declared the match a draw, a decision that dismayed the crowd which “vociferously objected.43”

The anger wasn’t unreasonable either—the bout had been advertised as “best two of three falls to a finish” and, well, there was no finish. Sitting ringside, Dr. Harry Martin of the California Athletic Commission told the press he was unaware of the rule in question and was displeased by the abrupt ending.

“McDonald pulled a boner when he did not force the match to a decision,” Martin said.44 “If he doesn’t know our rules any better than that he has no right in the ring.”

A 60-day suspension was handed down45 to the official and a new rule developed to insure “a decision must be reached in any finish match.”46 In today’s terminology, the Commission basically declared the next time Londos battled a contender in California, the bout would have no time limit.

Putting the heat on McDonald was a clever bit of business, a call back to the earlier mini-controversy that led to Londos having personal say in who officiated the match. When asked by the press about his suspension, the busy referee just laughed. The newspaper gimmicks hadn’t touched him out in the real world—he was officiating a card that night in San Diego.47 His suspension was officially rescinded48 three days later, but it had played its part well, adding a narrative beat to the never-ending serial we call pro wrestling.

The new rules presented a handy gimmick for the next time the two met and, in the meantime, some local promoters began referring to Steele as the “uncrowned champion.” Londos, for his part, packed his $10,000 belt in a suitcase and was off to Seattle for another title defense that weekend. Every walked away smelling like roses, fitting for a match promoted by Daro, a man known as the “Carnation Lou.”

Jonathan Snowden is a long-time combat sports journalist. His books include Total MMA, Shooters and Shamrock: The World’s Most Dangerous Man. His work has appeared in USA Today, Bleacher Report, Fox Sports and The Ringer. Subscribe to this newsletter to keep up with his latest work.

The St. Louis Globe Democrat said $7500 and Londos biographer Steve Johnson has it at $3000. But what’s a few thousand bucks among friends? It’s value was between $69,000 and $230,000 in today’s money depending on whose estimate you go with.

One described by newspaper columnist Paul Gallico as “big enough to hang your hat on.”

Rival Gus Sonnenberg and the embarrassing Wayne Munn, both ex-football players, were conspicuous by their absence.

The guest list was set at 100 but somehow 200 people found their way into the ballroom, no doubt creating plenty of stress on the staff. The fact many were big men, with big appetites, surely didn’t help.

You’ve got to see this guy for yourself: https://5008.sydneyplus.com/HistoryColorado_ArgusNet_Final/Portal/Portal.aspx?component=AAFG&record=c718a074-99d3-47b2-80e5-f5aef42cdd6a&lang=en-US

Daily News (1/27/1931)

Jim Londos: The Golden Greek of Professional Wrestling, Steve Johnson (McFarland, 2025)

Londos was not the only title claimant at the time. Another faction, led by Paul Bowser, Billy Sandow and wrestler Ed Lewis, ran a competing circuit of their own.

Wrestling in the Garden, Scott Teal and J. Michael Kenyon (Crowbar Press, 2017)

“And this at a time when most professional sports are having trouble keeping their heads above water,” the Phladelphia Inquirer opined.

Philadelphia Inquirer (12/13/1930)

Legends of Pro Wrestling, Tim Hornbaker (Sports Publishing, 2012)

Ringside: A History of Professional Wrestling in America, Scott Beekman (Praeger, 2006)

See Ed “Strangler Lewis Facts Within a Myth by Steve Yohe for more on Mondt and Curley’s war on Londos.

Ballyhoo!, Jon Langmead (University of Missouri Press, 2023)

Los Angeles Evening Post-Record (7/7/1932)

Brooklyn Citizen (4/22/1932)

According to Fall Guys author Marcus Griffin, many hands were reaching into Jim’s pockets: “Rudy Miller, Jack Curley and myself were to get five percent of Londos’ earnings. Mondt, who was already cutting Londos for 25 percent as a partner of Tom Packs, Ed White and Londos in the St. Louis faction, was to continue to split up with these three, sharing equally in the profits after the others in on the jackpot had been taken care of.

Besides our 15 percent, the kitty was to be socked for 7% percent for Ray Fabiani, the Philadelphia promoter, who was to put on the match that was to make Londos champion; and 5 percent was to go to Hans Steinke, who was Londos’ policeman.”

The Buffalo Times (10/2/1932)

The best came, not from a wrestler, but from Runyan, who wrote that Lewis looked like “he may have inadvertently swallowed a water-melon whole.” The less erudite Evening Star in Washington, DC put it more plainly, calling him “very, very fat.”

Los Angeles Evening Citizen News (4/2/1932)

Sepulpa Herald (9/2/1932)

https://www.norkarussia.info/peter-sauer-aka-ray-steele.html

Daily News (Los Angeles) (7/13/1932)

The Billings Gazette (10/11/1922)

Hooker, Lou Thesz with Kit Bauman (Crowbar Press, 2011)

Cleveland Press (2/4/1932)

Los Angeles Evening Post Record (6/1/1932)

The Buffalo Times (10/2/1932)

Intelligencer Journal (1/8/1927)

It was considered one of the great ballparks in the country. More here: https://sabr.org/bioproj/park/wrigley-field-los-angeles/

Los Angeles Evening Post-Record (7/9/1932)

Other reports had Londos training further south at Laguna Beach.

Pesek challenged Londos a few days later, adding fuel to the fire.

Daily News (Los Angeles) (7/16/1932)

Evening Vanguard (7/16/1932)

Gus Sonnenberg to Don George to Ed Lewis for those keeping score.

The Sacramento Union (3/7/1932)

Daily News (Los Angeles) (7/18/1932)

Reported as 10,000, 12,000 or 20,000 depending on the source.

New Yorker (11/13/1954)

Los Angeles Evening Post-Record (7/19/1932)

The Daily Breeze (7/19/1932)

The Pasedena Post (7/20/1932)

The Los Angeles Times (7/20/1932)

Pasadena Star News (7/20/1932)

Press Telegram (7/20/1932)

Press Telegram (7/23/1932)

Yes , George was married to Babe. We had two Babes in the family, uncles George's wife and Babe the wrestler. Some people get confused on that. George was the first to enter wrestling in 1928! So he was in there and headlining a lot of matches in the 1930's against most of the top names.

Uncle George really helped Lou Thesz get over in St. Louis when Tom Packs loaded up a card and gave Lou a big push when he was ready.

My uncles, The Zaharias brothers, George, Chris, Tommy and Bade. Actually, Uncle George wrestled both Jimmy Londos and Ray Steele many times. Steele is a personal favorite of mine.