The Man Who Beat Dan

Larry Owings, Dan Gable and The Real Biggest Upset in NCAA Wrestling History

On Saturday Wyatt Hendrickson stunned Olympic champion Gable Steveson to win the NCAA heavyweight title. On the broadcast, former UFC champion Danile Cormier called it the biggest upset in tournament history. But was it? Combat sports historian Jonathan Snowden takes a look at another match that shocked the world.

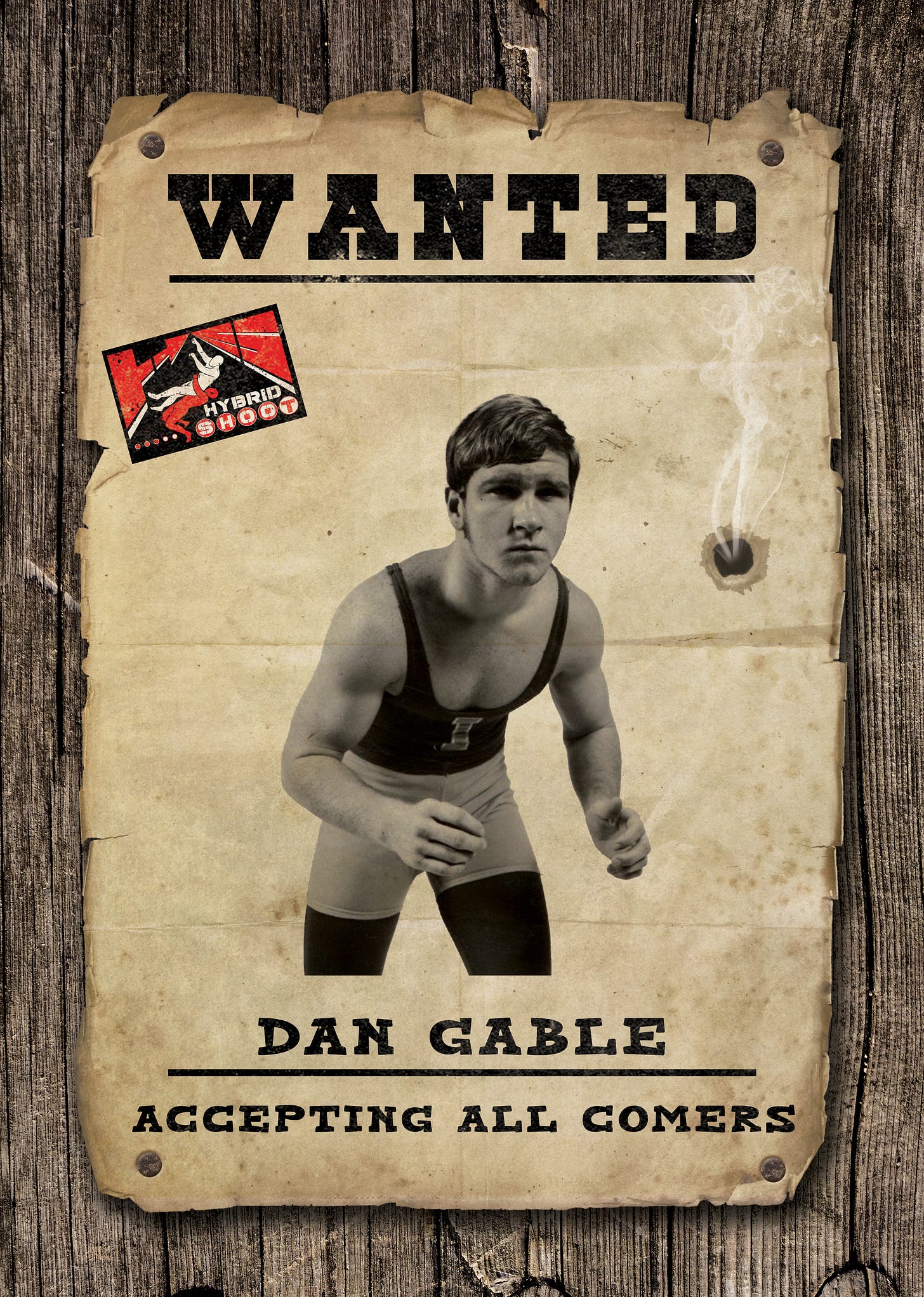

The NCAA tournament in 1970 was supposed to be little more than a coronation. Iowa State’s sensational senior Dan Gable, after all, was being heralded as the best collegiate wrestler since the other Dan.1

Consecutive NCAA titles will do that.

His run in 1969 concluded with a fifth consecutive pinfall. No one who stood across from him at the tournament that year managed to escape without having their shoulders planted on the mat. Undefeated in folkstyle wrestling going back to his high school days, a total of 181 outings without a defeat, some whispered he might be even better than the immortal Hodge himself. Bold words back when wrestling fan’s memories of the Oklahoman’s Sherman-like march through his rivals were still fresh.

The press department at Iowa State sent a five page dossier to newspapers from coast to coast, spreading the gospel of Gable to the nation. To say “they bit” would be an understatement.

“Dan Gable…The Greatest” blared one representative headline. “Greatest Ever” read another caption.

“The most widely renowned performer in college mat history,” Tulsa World crowed.

“It was almost taken for granted that Dan Gable was invincible,” Newsday reported, “a modern day Hercules at 142 pounds.”

Sports Illustrated’s Herman Weiskopf, not to be topped in the hyperbole department, compared him in appearance and demeanor to another midwestern icon—Superman:

When not competing, Gable…like Clark Kent, peeks out at the world through horn-rimmed glasses. But in his red uniform, with the big gold "I" on the chest, he has so aroused wrestling crowds they have been known to chant, "Kill! Kill! Kill!"

Unlike his famed Kryptonian counterpart, Gable came about his powers the old-fashioned way, the human embodiment of grit and hard work. In high school he tossed cinder blocks with a cement crew and cut grass with a push mower instead of using the power variety—that is, when he wasn’t chasing cats on rooftops or winning multiple state championships.

For Gable, wrestling was a full-time gig. He went hard year round. “December to December” he was fond of saying, treating the sport like a job, working at his craft 40 hours a week. Even that wasn’t enough—he’d run everywhere to get the extra work, sprinting to and from class just to be sure he wasn’t falling behind some theoretical rival who might conceivably work harder. He’d wake up at 2 AM and knock out some pushups. After all, you never knew what the other guy might be doing to get just a little bit better while you were doing something lazy like sleeping at night.

“After I won so many without losing in high school, I never wanted to do anything but win,” he told columnist Al Miller. “Once you win you want to keep winning…I’m more sure of myself now and I try to be more aggressive. For instance, from the time my match begins until it’s over I’m trying everything I know to get a pin.”

His aggressive streak paid off, pin following pin in a season for the ages. Eventually he’d ran up a streak of 25 straight, an NCAA record.2 Even the match that broke the streak was hardly a nail biter. Gable won 25-1 and many observers thought a pinfall could have been called at several points.

That kind of success doesn’t go without notice. A week before the tournament, he had been named wrestling’s “Man of the Year” donning a jacket instead of a singlet in front of the sports’s power brokers. The notoriously shy Gable went up to accept the award the night before the tournament and merely nodded at the audience who erupted in applause. When it died down he nodded again, then all but ran off the stage without saying a word, mortified by attention anywhere other than the wrestling mat.3

But attention was getting hard to avoid, especially as it became apparent he was an elite, world class athlete. He received the key to the city of Ames, Iowa when the town celebrated “Dan Gable Day” and was feted seemingly wherever he went. Gable was such a force of nature that people were hopping weight classes like bunnies, desperate to stay out of his bracket. Hodge had been a similarly imposing presence.

One man, however, wanted nothing more than to lock horns with the greatest wrestler in the world. His name was Larry Owings, a sophomore at the University of Washington—and he was out for revenge.

Owings, who had won the Pac 8 championship at 158 pounds, dropped two weight classes for the national tournament.4 Despite a dislocated thumb and an injured tailbone, Owings wasn’t merely running towards Gable when everyone else was running away—he was talking about it, his self belief broadcast to the world in august publications like the Chicago Tribune.

"I want to face Gable for the championship," Owings told the press on the first day of the tournament. "I faced him at the Olympic Trials in '68 and he beat me. I was a high school senior, and he was already a national champ. I made up my mind back then that I wanted to meet him again and beat him.

“…I think 142 is right for me. Last year I made a mistake at the Nationals by cutting too much weight. I had decided to avoid Gable [Dan competed at 137 pounds], so I cut down to 130. I won three matches. Then I lost 14-12 because my stamina was low. Right then I decided to go after Gable this year.”

The fifth of five state champion wrestling brothers, Owings called Hubbard, Oregon (population 900) home. While wrestling wasn’t forced on him, watching his brothers earn glory on the mat primed him for the sport. His family, which had nicknamed Larry “Porky”, didn’t have high hopes for the youngest member of the clan. Losing every match his freshman year didn’t help.

Soon enough, however, he’d conquered the state just like his brothers.

“It just seemed the thing to do,” he told the Associated Press. “It was kind of expected.”

Even in Hubbard, however, you’d have been hard pressed to find many takers in a bet against Gable, despite Owings national titles the previous year in both Greco-Roman and freestyle wrestling. Only two other people truly believed Owings had a chance: his girlfriend, who threatened to crumple his fender if he lost5 and his high school coach, who called him the best wrestler ever produced in the state of Oregon.

Gable’s coach, Harold Nichols, apparently wasn’t impressed with Owings’ bravado, dismissing him outright mid-tournament and openly questioning his decision to put himself in front of the battering ram better known as Dan Gable.

“Maybe Owings figured he could be second best at 142 and he would only be third at 150,” he sneered6, even as the Washingtonian destroyed everyone in his path, pinning them all at an even faster rate than Gable himself. An ABC reporter named Bud Palmer was equally incredulous according to Owings biographer Michael Gerald7:

Larry, why, particularly with such a successful sophomore season in the Pacific loop at 158 pounds, would you drop a weight class that will be impossible to win because of Gable's presence?" Palmer asked.

Larry's eyes burned audaciously. He was first silent, then he spoke slowly and concisely.

"I'll beat him," he stated in the most determined tone imaginable.

Although the doubters burned at him, in fairness Owings’ decision likely seemed ludicrous to most. Credited in the media with drawing more than 30,000 fans to Northwestern University’s McGaw Hall for the event, Gable appeared destined to win another title, his third in as many weight classes. The tournament featured the largest field in NCAA history8—but it was clear who fans were there to see, thousands of spectators shifting seats depending which mat Gable was on, competing for the best view.

On the day of the final, the world’s greatest wrestler was not himself. He’d stressed himself out at an awards banquet, then fumbled his way through a series of television interviews for ABC’s Wide World of Sports. The producers wanted him to record a promo for the next week’s show, touting his victory and the successful completion of an undefeated college career. But, perhaps because he hadn’t yet secured the win he was boasting about, Gable was flubbing his lines right and left, requiring more than 20 takes before eventually satisfying the requirement.

Busy with television, he hadn’t done his regular warmup. Worse, Owings had crept into his head, causing Gable to sit and watch some of the other matches in his bracket, something he wasn’t in the habit of.9 It was, as Brian Meehan explained in The Oregonian, an unfamiliar feeling for the normally uber-confident young wrestler:

Owings had gained the psychological edge. The challenger’s prediction of victory had drawn the champ’s attention. For the first time in his career, Gable entered the match thinking about his opponent’s moves. He is worried about Owings’ cradle, a lethal pinning hold.

“I wasn't maybe in the best mindset like I had been in the past—I still thought I was going to win,” Gable said in an interview for a documentary about the match. “I think I would have beat most people, I really do. Even in that mindset. But he had done a great job of getting himself ready mentally to attack me and to wrestle me.”

There was a full house for the final, nearly 8,000 packed in tight, not just to see a wrestling match but to witness the first draft of history, “to watch a red-headed Main Street hero step across the threshold of legend.”10

Larry Owings had other ideas.

While the public had come out to celebrate a Gable victory, the two wrestlers were both firing on all cylinders, even if the crowd was much more familiar with one than they were the other.

“He pinned his way all the way to the finals, and I pin my way all the way to the finals,” Owings said. “And I don't know if that's ever been done before or since…And in the finals we met, he was already a two-time national champion, and had won the Outstanding Wrestler in the national tournament but I was I was ready for him. I was sky-high and prepped and in good shape.”

In a barn-burner of a match, he pushed Gable to his limits and beyond, securing victory with a takedown and a pinning predicament in the final minute to claim both the national title and the tournament’s outstanding wrestling award. It was, as the Chicago Tribune’s Tom Tomashek declared “one of the most unforgettable moments in the history of the sport and possibly all sport.”

“My strategy going into the match was that I was going to throw anything and everything that I had against him and keep him so busy and on the defense that he could not use his offense against me,” Owings remembered. “And that's what I did. I kept him off balance the whole match so he really couldn't ever get any momentum going and and beat me. That's that's how I did it.”

It was, Jairus Hammond wrote in History of Collegiate Wrestling, the biggest upset the NCAA tournament had ever seen:

Larry Owings did the impossible— he beat Dan Gable in the last match of his collegiate career, thus spoiling his 96-0 perfect record. Owings, who was probably the only person in the building who thought he could win, surrendered an early takedown before scoring seven straight points to lead 7-2. However, Gable rallied and knotted the score at 8-8 with a reversal early in the third period. Owings escaped then took Gable down, briefly exposing his shoulders. Referee Pascal Perri awarded two back points to give Owings a 13-8 lead. Gable escaped and had two points for time advantage, but Owings, the tournament's Outstanding Wrestler, was a 13-11 victor.

The signature move of the bout was Owings’ fireman’s carry, “the only thing I planned in the whole match,” he said afterwards. His coach, Jim Smith, called it “the greatest fireman’s carry I’ve ever seen.” If not the greatest, it was certainly among the most consequential.

Suddenly Gable found himself wrestling from behind, an unusual dilemma for a wrestler best known for his systematic decimation of foes and quick finishes. He managed a rally, then lost momentum again when a lost contact lens caused a brief pause in the bout.

At the end of the final stanza, Owings prevented a last ditch comeback by shooting a takedown of his own, once again stymying Gable with endless offense. For a moment, after the final horn, both young men sat dazed on the mat, eventually prodded by the referee to “stand up fellas, it was a great bout.”

The two exchanged handshakes on the mat, as the stunned Gable tried and failed to process what had just taken place.

“When it was over,” Owings said after the match11, “I looked at Dan and he looked like he didn’t know what had happened.”

Gable confirmed that perception immediately after the bout. Looking equal parts confused and dejected, he hung his head as he walked slowly off the mat.

“I can’t remember anything that happened in the last 40 seconds,” he told the media. “When I looked up at the scoreboard and saw he led 13-9, I couldn’t believe it.”

“He tired me out more than I thought he would and I wasn’t able to ride him long enough to collect points,” Gable told the Chicago Tribune. “Owings was very squirmy and hard to control.”

In the locker room, teammates were despondent. Chuck Jean, the defending champion at 177 pounds, was already in the shower, ready to dress and go back to the hotel without even competing. Only Gable’s personal intervention convinced him to go out there and win another title. Iowa State took home the team trophy. But it felt more like a funeral than a celebration.

“I tried to (talk to Gable after the match),” Owings said.12 “He wouldn’t have anything to do with me.”

“I was crushed,” Gable told Season on the Mat author Nolan Zavoral, his voice quivering years later. “I hurt.”

At the medal ceremony, tears spilled down the vanquished champion’s face as the crowd gave him a standing ovation that lasted between one and five minutes depending on the source, a tribute to their fallen hero.

“During that time Gable slowly raised his head until it was erect,” Sports Illustrated reported. “Even in victory he had never been so honored nor received the tribute of a crowd that expressed itself more eloquently.”

For Owings, it was a career highlight. He battled twice more for NCAA primacy but finished second both times. Then, in a rematch two years later, Gable eliminated him from Olympic contention in a comparatively dull bout the winner wrestled with great care.

The match in 1970 had been a burden for both. Gable had worried if Owings’ had his number. Owings was concerned his legacy would be limited to being a footnote in someone else’s story. Being the man who beat the man wore on him, creating an impossible standard he found hard to duplicate. The attention also weighed heavily on a very private person.

“I was kind of an introverted person,” Owings would recall years later. “Still am. And there were times after that I didn’t like the monkey of Gable being on my back. ‘There goes Larry Owings who beat Dan Gable’ rather than ‘Larry Owings who was a great wrestler.’ I hated the publicity. I just wanted to go in and wrestle and go home and be a regular person. It was hard living up to people’s expectations all the time and trying to be what they wanted me to be.”

For Gable, after a little time to process the guilt he felt about letting down family and teammates13, the loss was both liberating and empowering, further fueling an engine that only revved at the highest competitive RPMs.

“Of course it haunts me, but guess what? I needed that loss,” Gable told Joe Rogan. “I really did. That loss took me to unbelievable heights that I would have never had without that loss.”

Without it, he believed, he might not have kept the mindset that pushed him to world and Olympic gold, then powered team after team at the University of Iowa to NCAA glory where he reigned as head coach for decades.

“It’s been my most monumental match from a learning experience,” he told The Oregonian’s Brian Meehan in an outstanding retrospective.14 “…At the time I would never have admitted that.”

The results speak for themselves. A world championship. An Olympic gold medal where no one scored a single point against him. Fifteen NCAA titles as a coach. Universal acclaim and a place on the Mount Rushmore of American wrestling.

It was an almost peerless and perfect career—except for Larry Owings.

And, for that, it should remain unchallenged as the greatest upset in the history of the sport.

The Two Dans in amateur wrestling lore are Gable and the legendary Dan Hodge, for whom wrestling’s version of the Heisman trophy is named.

According to InterMat, he had pinned 83 his 118 opponents in college, winning an incredible 70.3% of his matches by fall.

Sports Illustrated (6/19/1972)

Owings had wrestled in five different weight classes in a two year career. Some movement was strategic. Others, perhaps, were tied to his self-confesses love of shrimp and food generally.

“She drove me to the airport and still has my '66 Malibu,” he told the media. “So I guess I'd better win.”

The Courier (3/27/1970)

As quoted at InterMat (https://intermatwrestle.com/articles.html/college/intermat-rewind-gable-owings-r72033/)

Sports Illustrated (4/6/1970)

The Gazette (2/12/1970)

Brian Meehan wrote the heck out of a retrospective for The Oregonian in 1990.

News Journal (3/30/1970)

Corvallis Gazette Times (3/31/1970)

According the his SportsCentury documentary on ESPN, Gable broke into tears again when he got home and saw the newspaper headlines.

The Oregonian (3/5/1990)

Just a fantastic piece. Thank you.

Fantastic story, now I have to look up that retrospective...