The Invisible Wall

Masakatsu Funaki and Minoru Suzuki were sold a revolution. What they got was business as usual.

April 15, 1990 – Hakata Star Lane

Masakatsu Funaki stood in the corner, looking across at Minoru Suzuki. It had been seven months since Funaki had been seen in a UWF ring. Seven months of silence. Seven months of “blank space.”1

Funaki looked different. The baby fat was gone, stripped away by stress and rehab. He was twenty-one years old, but he wore the face of a man who had seen too many losing tickets. He pulled a photo out of his bag—a snapshot from his European excursion just a year prior. He stared at the smiling kid in the picture.

“It feels like I’m looking at my younger brother,” he said, his voice quiet. “I look about 20 years older now.”

The crowd in Hakata was waiting for a show. Funaki had previously made waves with the "Bone Method" (Koppo), a controversial style utilizing palm strikes that KO'd Nobuhiko Takada and brutalized Bob Backlund.2 They wanted the fireworks, the “U-Style” flash, the ultra-violence Funaki had become famous for.

But Funaki and Suzuki weren’t selling fireworks this night. They were selling the truth.

The bell rang. They didn’t kick. They didn’t punch. They collided with a dull thud, locking horns in a silence eventually so thick you could choke on it, every catcall clearly audible.

It wasn’t necessarily what the crowd paid for. They wanted the noise. They wanted the crash. As the two men struggled on the mat, fighting for inches in a ‘monochrome’ stalemate, a voice rang out from the darkness.

“Do it seriously!” a fan screamed.3

Funaki didn’t flinch. He didn’t speed up. He knew what the fan didn’t: This was serious. This was as serious as a heart attack. The fan wanted a show. Funaki was giving him a fight. This was more than a grappling exhibition. It was a preview of the future.

See the match

The Rigged Game

April 1989 – One Year Earlier

A year earlier, Funaki and Suzuki walked out of New Japan Pro Wrestling. They were the “Young Shooters,” the defectors who told the world they were tired of the circus. They were coming to the UWF for the “Real Fight.”

The fans bought it. They lined up around the block, cash in hand, desperate to see the young wolves eat the old lions. But the UWF had a dirty secret. It wasn’t a meritocracy. It was a bureaucracy. It was sold as a revolution. Instead, it was plain old wrestling, just different faces sitting at the top of the poster.

The press knew it. The boys in the back room at Weekly Pro Wrestling had already figured out the scam:

“The UWF has an ‘invisible ranking’ exists. There is a hierarchy they cannot overcome. They hit a wall where power is strictly a matter of time served.

“There is a cold logic to why the ‘Class’ system in pro wrestling remains static: The Front Office is active, but the wrestlers are passive. Fujiwara, Funaki, and Suzuki were treated not as revolutionaries, but as outsiders who just got off the bus. Inside the UWF, the power dynamics are set in stone. The interesting part of the UWF—the chaos—was swallowed up by ‘UWF Politics.’”

Akira Maeda was the Boss. Nobuhiko Takada was the Underboss. And the kids? They were just extras. The Office didn’t want Funaki and Suzuki to take over. They wanted them to look good on the bottom of the poster, to capture the attention of younger fans before inevitability slotting into the right place.

The Front Office didn’t want an actual revolution. They wanted a marketing campaign. They took all that fire, all that dangerous energy Funaki and Suzuki brought to the ring, and they used it to sell tickets—not to change the hierarchy. They weren’t fighting for supremacy. They were just fighting to expand the brand.

Funaki and Suzuki hit the “Invisible Wall.”

They realized too late that you can’t fight your way up a ladder when your feet are nailed to the floor.

The Desperate Bet

September 1989 – The Injury

Funaki, once thought to be a sure thing to go far in New Japan, got desperate. Even at 20, he knew that in this business, if you aren’t moving up, you’re moving out.

The Tokyo Dome show was coming up in November. “U-COSMOS.” The big time. The Front Office lined up a killer named Maurice Smith—a kickboxing champion who cut people apart with surgical precision. This was Funaki’s chance. If he could beat the outsider, he could break the Wall.

He started sparring with Suzuki. He pushed too hard. He threw a spinning backfist with bad intentions. Suzuki blocked it. Crack. Funaki’s left forearm snapped. A hairline fracture.

A smart man would have taken the time off. But Funaki wasn’t smart; he was terrified. He was terrified that if he stepped out of line, the Invisible Wall would close up and leave him on the wrong side.

Possibly forever.

Once established as a middle of the pack man, it was hard to push your way to the top. The fans already thought of you a certain way. So he did the unthinkable. Ten days after his trip to the hospital, he took a pair of shears and cut off his own cast.

“I want to separate the bone quickly so I can cure it faster,” he told himself. “If I don’t move it, it won’t heal.”

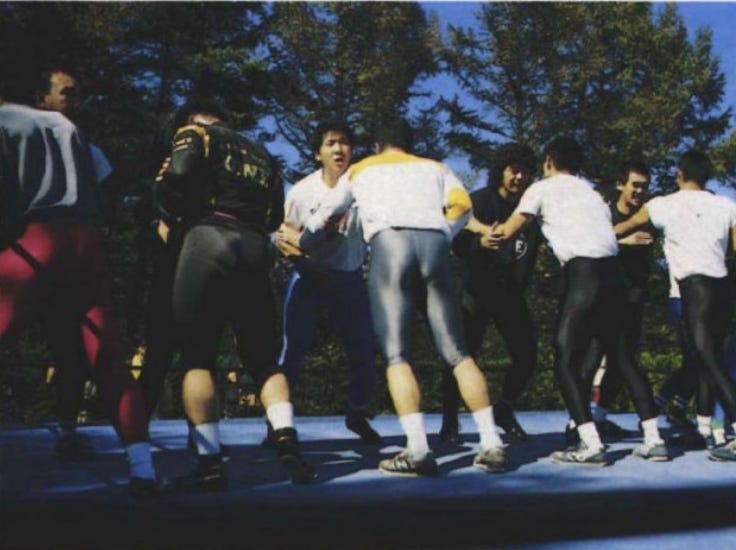

It was the logic of a junkie. Or a crazy person. He went to the training camp at Lake Yamanaka despite his injury. The whole crew was there, the kind of training that was part mandatory fun, part publicity stunt.

The cameras were rolling. He had to look strong. He lay down on the bench press. He loaded the bar. His arm screamed:4

For the UWF Tokyo Dome event, we decided to hold an intensive training camp in Yamanashi, and I participated as well. There was TV coverage, and I did the bench press there.

Usually, I was lifting 80kg, but because the cameras were rolling, I set it to 100kg. Since two weeks had passed and the pain in my arm had subsided, I thought, ‘It’ll be fine,’ and challenged myself.

At that moment, I snapped the bone that was in the process of healing. Crack.

Because of this, I missed the Tokyo Dome show and was forced into a long-term absence.

He had bet the house and busted.

The Fall Guy

November 29, 1989 – The Tokyo Dome

The Organization needed a body. Funaki was out. So they pointed the finger at Suzuki.

“You’re up, kid.”

The white arrow had landed with a thunk.5 Suzuki knew he was walking into a slaughter. He was a grappler, an amateur wrestling standout; Smith was a striker who later ate grapplers for lunch, even winning the Ultimate Fighting Championship in the sport’s dark ages. But you don’t say no to the Front Office, to opportunity when it knocks.

Suzuki walked into the Tokyo Dome wearing a brand new, pure white costume. It was a nice touch. By choosing pristine white, he likely intended to symbolize a fresh start or the purity of his fighting spirit.

After his crushing, one-sided defeat, however, the press seized on the darker symbolism. By wearing all white, they argued, Suzuki had inadvertently dressed himself for his own funeral. Historically, samurai would sometimes wear white beneath their armor—or dress entirely in white—before a battle from which they did not expect to return. It was a statement of resolve: “I am ready to die.”

Maybe he didn’t realize it, but the media did, calling his white gear exactly what it was— his ‘burial shroud’ (death outfit).”6

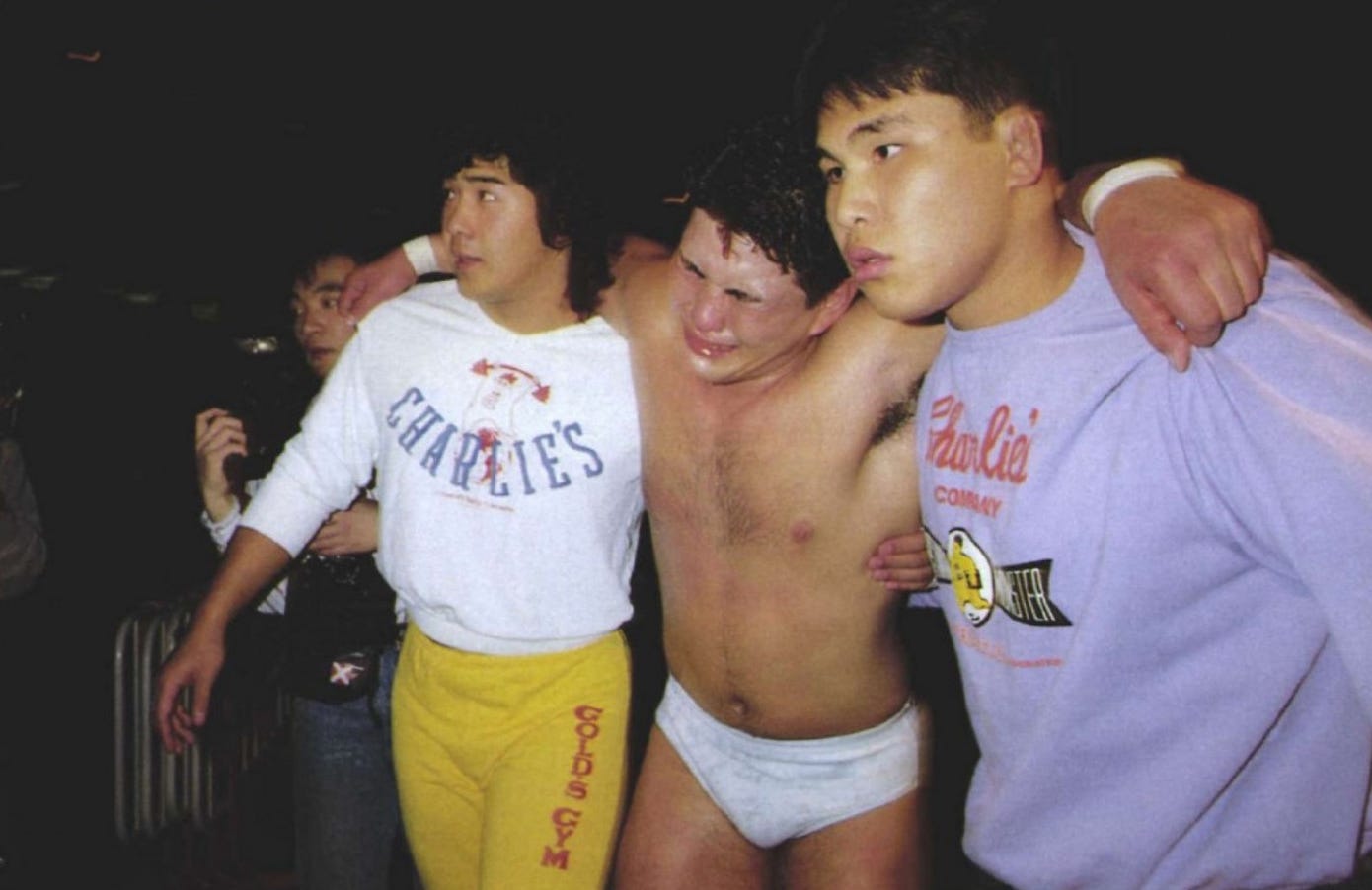

Before the fight, the young Japanese wrestler tried his hardest to look tough. He put on his best “Gonta” face—a thug’s sneer to hide the fear.7 It didn’t work. Smith picked him apart. In the fourth round, Smith put a right hand on his chin and turned the lights out. Suzuki lay on the mat, crying. Not because it hurt. But because he realized he was nowhere closer to his goal.

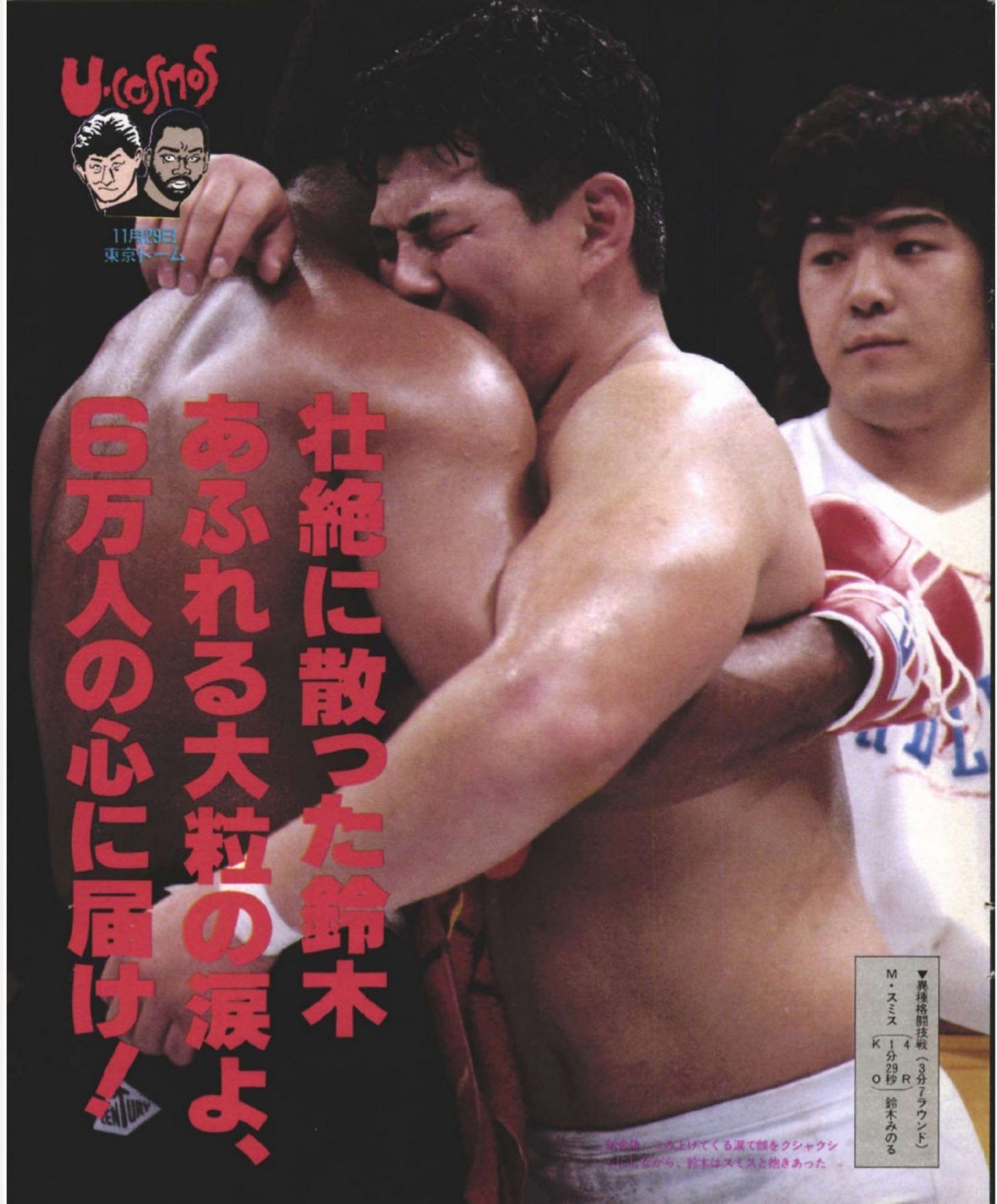

Early mixed martial arts (11/29/1989)

“Suzuki, his face crumpled in tears, looked up at the ceiling,” Weekly Pro Wrestling reported. “From the bottom of his heart, he hugged Smith.”

For the young heroes, losing wasn’t a mere setback. It was a call from the fighting gods to get stronger.

The Settlement

April 15, 1990 – The Finish

Back in Hakata, the two young bulls met in the middle of the ring, pointedly refusing to wreck the China shop. Funaki and Suzuki wrestled for eight minutes and fifty-three seconds. Wrestled. It wasn’t a performance. It was a receipt, a statement. Suzuki went for the leg. He got sloppy. Funaki caught the ankle and twisted. “It hurts! It hurts!” Suzuki screamed.

He tapped out.

Funaki got his hand raised. He took the microphone, but he didn’t brag. There were no histrionics. He spoke like a man who had looked into the abyss and blinked.

“Humans...do not know when they will die. If by some chance tomorrow I die, I want to have no regrets.”

Suzuki sat in the hallway afterward, smiling a bitter, crooked smile.

“Even though I lost,” he said, “I finally did pro wrestling.”

They packed their bags. Funaki had his win. Suzuki had his pride. But as they walked out into the Fukuoka night, the Invisible Wall was still there. The revolution was forestalled.8 Their ranking—that damn, invisible status—hadn’t moved an inch.

Jonathan Snowden is a long-time combat sports journalist. His books include Total MMA, Shooters and Shamrock: The World’s Most Dangerous Man. His work has appeared in USA Today, Bleacher Report, Fox Sports and The Ringer. Subscribe to this newsletter to keep up with his latest work.

“Blank Space” (Kuhaku) Kuhaku means a vacuum, a void, or a blank.

The Weekly Pro Wrestling writer covering this match uses the phrase to describe the grappling exchanges. To an uneducated eye, it looked like “nothing” (a blank space) was happening. But for Suzuki and Funaki, that “nothing” was filled with intense mental and physical density. It reclaims the “boring” parts of grappling as meaningful “white space” in the art.

“Koppo” (Bone Method) Koppojutsu is an ancient Japanese martial art focused on breaking bones and damaging internal organs, often utilizing palm strikes (shotei) rather than closed fists. In the late 80s, before the NHB revolution, this was viewed as a “lethal” technique. Funaki using it was seen as him crossing the line from “wrestling” into “killing,” hence the controversy about him losing his “wrestling soul.”

The system they're trapped in had already shaped expectations so thoroughly that authenticity reads as failure.

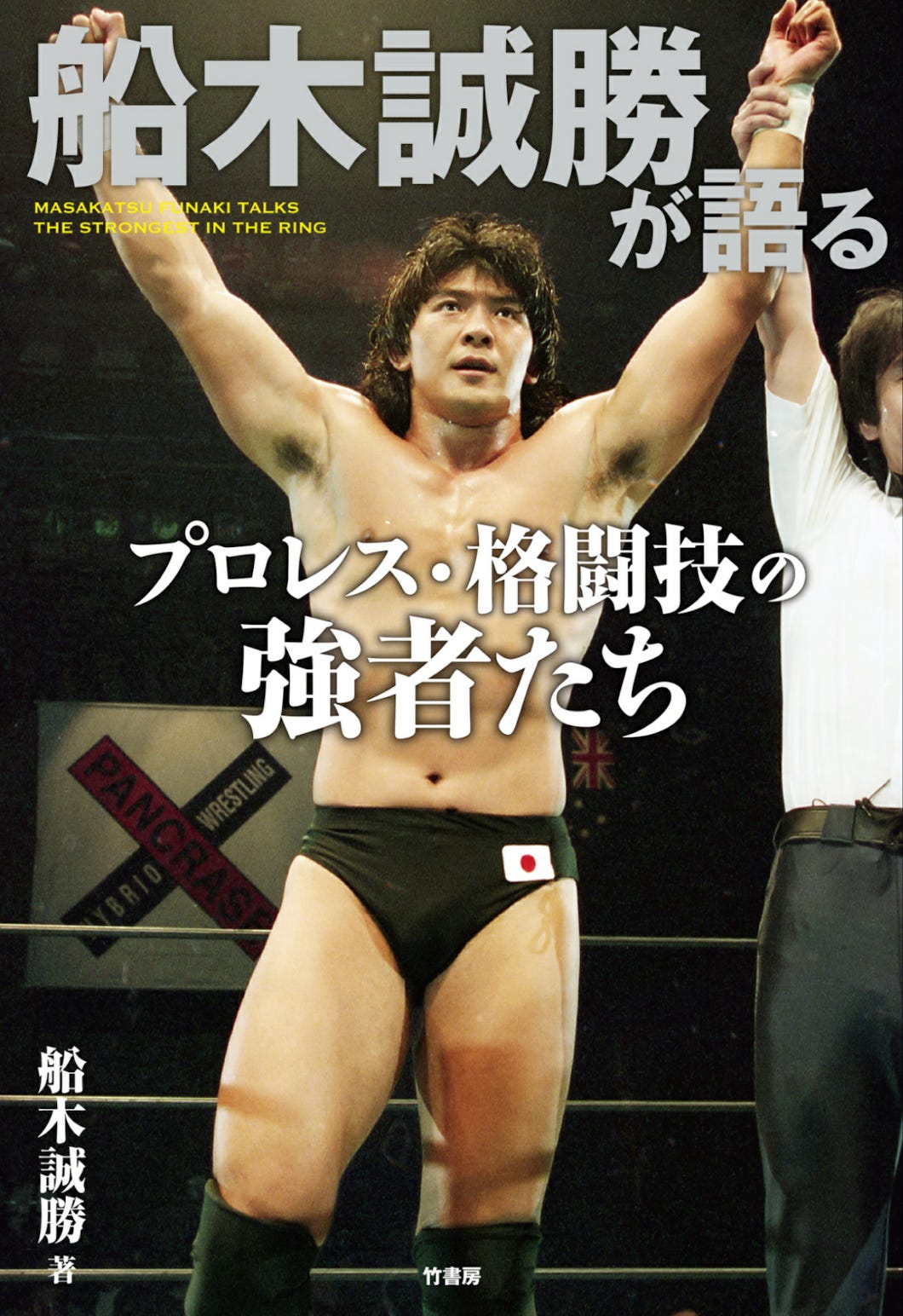

Details here from Funaki’s new book Funaki Masakatsu ga Kataru Puroresu - Kakutogi no Kyoshatachi (船木誠勝が語るプロレス・格闘技の強者たち).

“The White Arrow Stood” (Shiraha no Ya) The phrase Shiraha no ya ga tatsu literally means “A white-feathered arrow has hit.” In Japanese folklore, if a white arrow landed on the roof of a house, it was a sign that the gods had chosen a girl from that home to be a human sacrifice. In contemporary wrestling, it meant to be singled out.

The White Shroud (Shini-shozoku) In Western culture, black is the color of mourning. In traditional Japanese culture, the color of death is white.

“Gonta” (ごんた) Gonta is a Kansai dialect term for a rowdy, naughty, or mischievous child—a brat who won’t listen. In a darker context, it can mean a thug or a hoodlum. By calling it a “Gonta face,” the Japanese writer was saying Suzuki dropped his professional athlete mask and reverted to his street-fighting, punk-kid roots to cope with the moment.

Eventually, Funaki and Suzuki would take matters into their own hands. By 1993 they would be presenting “real pro wrestling” in the most convincing manner yet, Pancrase the ultimate exemplar of the U-Ethos. But, for the time being, the Front Office was still firmly in control.

I remember seeing this match and wondering why it felt so startling--to me and to the audience. Great to have all this well-assembled context!

Would love to see a continuation of this story on here in the vein you had mentioned if it can’t be worked into a full-scale book. I’ve been locked into watching old Pancrase footage and this is great context for its origins.