Buried Treasure: Hackenschmidt vs. Rogers and the Match Thought Lost to Time

The Real Story Behind the Recently Rediscovered Footage From a 1908 World Title Match

Last week wrestling fans got a special treat—a beautifully restored match from 1908 featuring the legendary George Hackenschmidt in glorious action.

Well known for his physique, physical strength and battles with Frank Gotch, the “Russian Lion” remained a mystery of sorts despite his high profile—after all, no one living had ever seen him wrestle in a match, a legend lost in many ways to time.

Now that’s changed. The discovery and restoration of the first ever Hackenschmidt film is a great story in its own right.

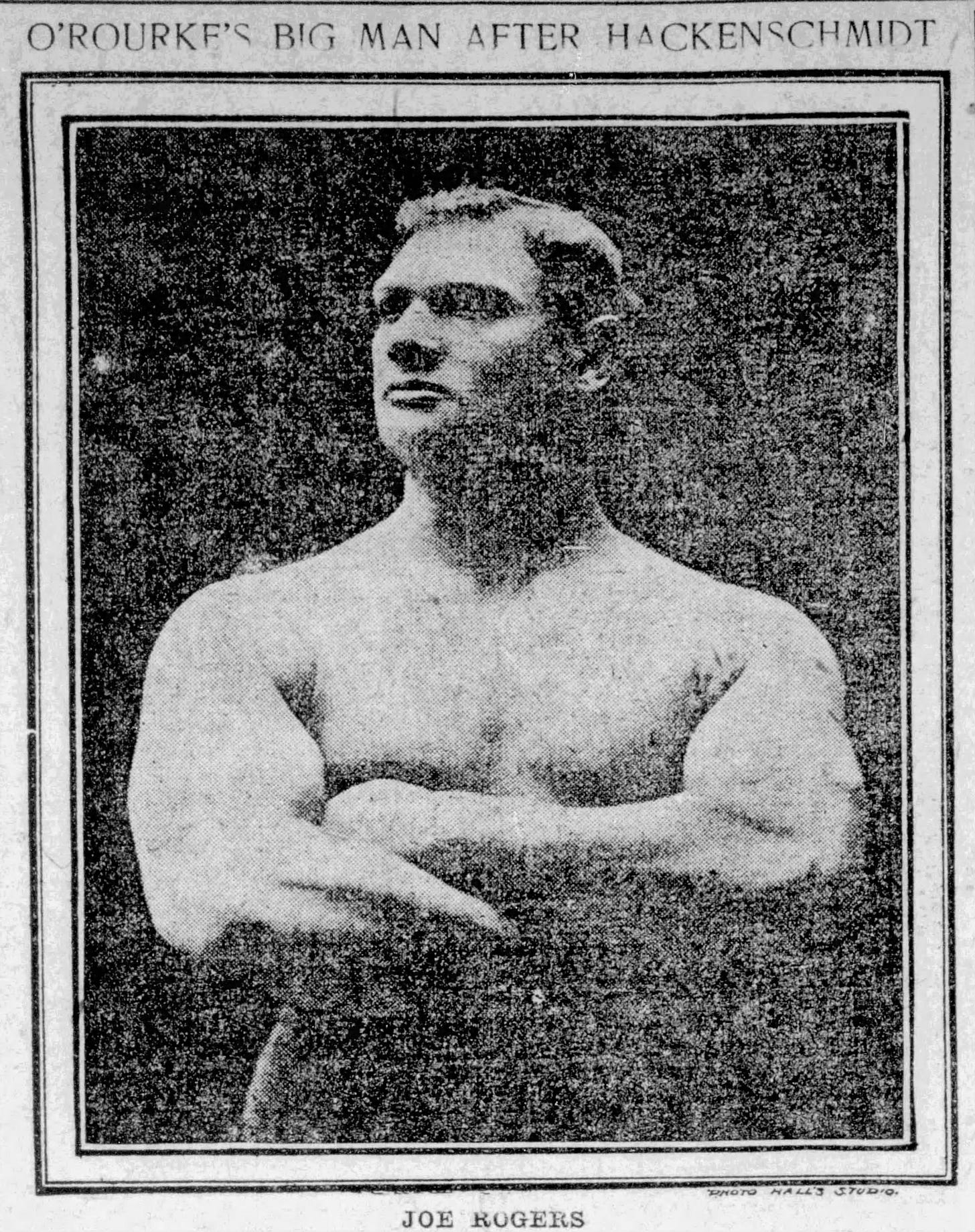

This, however, is the tale of the match itself, a title bout with a big galoot known alternately as “Apollo”, “Yankee Rogers1” and just plain Joe Rogers. It’s under the latter name that he challenged the great Hackenschmidt—this is his story.

Considered an enormity in his time, Joe Rogers stood a whopping 6’2” in an age when many people could go all day without seeing anyone who topped six feet ( just one in 208 Americans measured that height in 1898) and the average man was a mere 5’6”. Approaching 300 pounds at his most gargantuan, he was close to double the weight of your standard citizen, so large people would come out to gyms where he worked out just to look at him, to set their eyes on a specimen considered more than human—Rogers was a bonafide giant.

His bulk attracted interest, especially among the sports of the day, despite the fact that Rogers was green in both boxing and grappling. Wrestling as Apollo, first in New York, most successfully in Montreal, and finally throughout the midwest, Rogers created a stir everywhere he went—right up until the point when, as a Canadian newspaperman wrote “there may be some doubt about his wrestling science.”

But the raw clay was very enticing—if skill could be added to his sheer size, the sky seemed the limit. Could he be among the top wrestlers on the planet? A potential challenger for the recalcitrant boxing god Jim Jeffries, to whom he bore a striking resemblance?2 Nothing seemed out of the realm of possibility, especially to Apollo himself.

Luckily for promoters on both sides of the Atlantic, Joe Rogers was a large man whose dreams were every bit as big as his biceps. On September 14, 1907, he boarded the steamer Abraham Lincoln for a five-day trip to England where he had a single goal in mind—the absolute domination of the British combat sports scene.

First to fall, he hoped, was the great George Hackenschmidt, the so-called “Russian Lion” and champion wrestler of the world who had made England his home away from home, wrestling hundreds of times around the country over the years. “Hackenschmidt has the joyous distinction of never having been hissed or booed by a London audience,” the Daily Mirror wrote, describing his rare popularity. “He is strong, quick, honest, and an exquisite showman…they love him.”

Such a hero deserves a proper foe—but after a grandstand challenge to the word’s wrestling champion in January, 1907 didn’t prompt any action (or even much in the way of newspaper coverage) Rogers decided to do other challengers one better—bringing the fight to the champion on his own turf.

Once that task was complete, he’d move on to Gunner Moir, the champion English heavyweight slugger, and take his title as well. Rogers had spent some time with the gloves on at the old Miner’s Bowery Theater in New York and even seconded Bob Fitzsimmons for a title fight with Jack Johnson. Like with wrestling, glory seemed just an opportunity away.

Bold plans for a bold man.

Even if it didn’t work, he hoped, the resulting press would launch him into a new stratosphere, a high-profile loss often better than a no-account win when it came to elevating a man’s standing with the public. All Rogers wanted, he said, was a chance.

“We tried to get on a match in this country but without success,” Rogers told the Buffalo Courier, whose reporter was taken with his abundant confidence. “Nobody seemed to pay much attention to me on this side, but I suppose if I make good in England there may be something doing when we get back.”

It was, as the Time-Union in Brooklyn wrote, some “nerve on the part of Rogers”, a plan concocted by Tom O’Rourke, a hall-of-fame boxing manager/promoter/regulator who was among the first to take American stalwarts across the sea for big paydays in England. O’Rourke, a fight sport lifer (he literally died in the dressing room before the Max Schmeling/Joe Louis fight in 1936), was taking on the biggest scheme he’d ever undertaken “and he has tackled some big propositions.”

Squawking from the moment they stepped off the boat, Rogers and O’Rourke did everything in their power to talk their way into a match with Hackenschmidt. While the potential boxing bout with Muir seemed out of reach (he was scheduled for a world title bout with Tommy Burns in December) the wrestling match remained a real possibility, one they devoted all their energy to.

Hackenschmidt, after all, often wrestled multiple times a week, albeit mostly in glorified exhibitions. Surely he could work Rogers into that schedule?

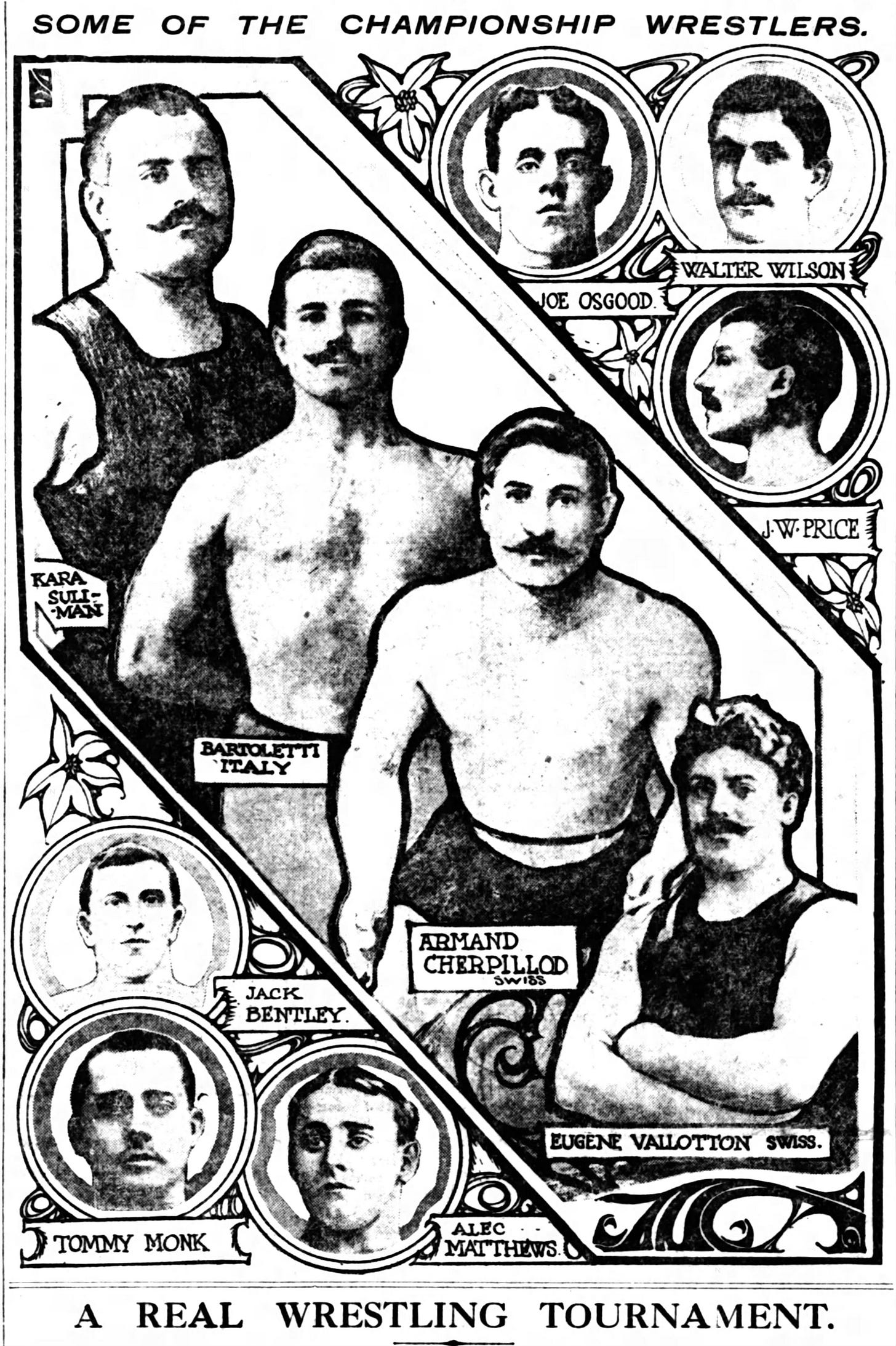

The London that Rogers rode into on the newly constructed electric tram was a wrestling fan’s paradise. The city drew wrestlers as a flame drew moths, all likely wanting to be in the orbit of the great Hackenschmidt, a star for years whose popularity attracted both crowds and money. When Rogers arrived, in fact, there were already two famous heavyweights awaiting their turn to tussle with the champ, Greco-Roman specialists Ivan Paudubny and Stanislaus Zybszko, who Hackenschmidt encouraged to face-off with the winner securing the honor of his attention.

Rogers initially inserted himself into the mix and an impromptu tournament was arranged, only for the big man to remove himself claiming injury, deciding instead to earn his title shot in a very modern way—by haranguing Hackenschmidt to the point he would take the match just to silence the American. Based out of Wembley, Rogers made his home in the Holborn Music Hall, facing “less celebrated” opponents while being “well boomed” by O’Rourke, who hounded the champion relentlessly.

It worked.

Hackenschmidt scheduled a match with Zbyszko, who’d earned the opportunity with a win over Padoubny,3 granting the Greco man several months time to prepare for a match in the catch-as-catch-can style which he now practiced exclusively.4 But he also agreed to take on Rogers as soon as possible, so long as it didn’t conflict with any of his pre-existing theatrical dates.

Despite critics complaining “Rogers’s claim to a match is based on so a slim a foundation,” Hackenschmidt was insistent. He was going to face this new, persistent challenger—no matter how unworthy he might have been.

On the day before Christmas, they signed papers making it official for the Oxford Music Hall at the corner of Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street on January 30, 1908.5

The match was on.

“All this time I was being incessantly challenged by Tom O’Rourke on Rogers’ behalf and attacked by the sporting press for not granting a match,” Hackenschmidt wrote in an unpublished memoir. “In the end I gave way to their importunities…I made no special preparation for the match but just carried on as usual.”

What was usual for Hackenschmidt, of course, was extraordinary for most. When the Manchester Dispatch sent a reporter to see the workout for himself, the routine amazed. Hackenschmidt easily snatched a 100 pound barbell over his head a score of times with each arm, then jumped over a desk 20 times from a standing position before deciding it wasn’t high enough, adding a box on top and continuing his leaps.

Presumably, at some point, some wrestling training was involved as well.

In the new world, news of the match was greeted with incredulity and even scorn, with one headline blaring “Joe Rogers’ Match With Hackenschmidt Will Be Huge Joke”, the author declaring “the Britishers do not appear to be Jerry to the fact that they are matching the big Russian with a second rater…Rogers is about as big a dub as could be found, but has the size and looks and O’Rourke is wise enough to keep him away from any one who might show him up.”

In the Denver News, writer E.W Dickerson didn’t know whether to be disgusted or impressed with O’Rourke who:

…is in England with Joe Rogers, the American wrestler, who he is starring as the champion of this country. It is a pretty raw piece of work, but O’Rourke is getting away with it and seems to be making money showing the “American champion.”

One person not amused by Rogers’ new title claim was the real American champion—Frank Gotch. When the cosplay champion declared “if Hackenschmidt can put me on upon my back, he will do what no man has ever yet done”, Gotch was beside himself. The Iowa farmer had met Apollo multiple times and defeated him in each instance. Though that was something Rogers had in common with, well, almost everyone Gotch ever stepped in a ring with, the real champion was furious that a pretender would secure the very thing he’d spent years campaigning for—a match with Hack.

“What right has Tom O’Rourke of New York to take a man like Rogers—a man I can throw ten times in an hour—to England to represent this country in a match for the world’s championship?” Gotch wondered aloud to the press. “I have tried hard to get a match with Hackenschmidt for the last two years but have not succeeded and the only conclusion to be reached is that he is afraid.”

Within months, Hackenschmidt would be on the doomed steamship the Lusitania, the fastest vessel on the sea, to prove that claim untrue. But that’s a story for another time.

In England, the excitement for his match with Rogers was building, the mega-bout scheduled simultaneously with an extended tournament at the Alhambra Music Hall.6 That tournament, called “real wrestling” in the Sunday Dispatch, promised “show business is to be entirely eliminated” with “no suggestion of tinsel and limelight.”

“The men,” the paper continued, “will be there to wrestle and not to talk.” Not mentioned by name in this critique, but notable by their absence from the proceedings, were all the leading lights of the London mat—including Hack and Rogers.

Philosophical differences aside, it was, the Daily Mirror declared, a “wrestling boom.” The analysis of the big match offered there was fairly straight forward— while Rogers relied mostly on his bulk, in addition to his peerless strength, Hack had wonderful quickness, smarts and “one thing more” alluding to rumors that most of his exhibitions were not, strictly speaking, actual competitive bouts.

“We shall most of us be surprised if Hack is thrown,” they concluded.

If Hackenschmidt was concerned about losing, he showed no sign. Rather than pull himself off the road to train for the bout, standard for big contests at the time, he continued his theatrical engagements right up until the match, even scheduling the bout for 2:30 pm in the afternoon. The reason? He wanted to be back in Manchester for his appearance that very evening.

Rogers, meanwhile, had discontinued all his obligations and was training “in proper style” at an “admirably fitted-up gymnasium.” The positive press was enough to sway some. Juicy odds were also being offered, with the hope of enticing Americans abroad to support their countryman with their wallets. Interest reached even the uppercrust, with two members of the Stock Exchange making a sizable wager on the result.

“The broker backing Rogers pins his faith to the Anglo-American’s superb condition and the natural advantages he had.” Rogers, if nothing else, passed the looks test. He might not have been much on the mat—but he certainly looked like a man who was, casting a dashing figure.

American papers, however, remained skeptical. “Hackenschmidt Has Easy Game in Big Joe Rogers”, one headline blared the week of the match, summarizing the general sentiment.

Personally, Rogers wasn’t as confident as he appeared on the outside. After all, he had good reason to fear the inevitable—unbeknownst to most fans in England, this would not be his first tussle with Hack. He’d been part of a sextet who wrestled the star in New York as part of a 1905 tour of America. Hack had beaten all six in just over 30 minutes combined.

In his popular column in New York’s The Evening World, celebrity sportswriter Robert Edgren recalled the evening with delight:

The referee called him back of the scenes and said: “Hack, don’t be in such a rush. You’ll get through with this bunch so fast the people won’t have a chance to see you. Let the next fellow stay longer.”

“All right,” agreed Hackenschmidt. “But I want you to know what I can do. I’ll let him stay until you give me a wink. Then watch.”

Joe Rogers was the next one. Hack toyed with him for eight or ten minutes, keeping his eye on the referee and anxiously awaiting the signal. At last the official winked.

Instantly, Hack seized Rogers about the body, picked him up, turned him over like a sack of flour, threw him violently to the floor and pinned his shoulders down before he had a chance to even wriggle. The actual effort consumed about four seconds.

Hackenschmidt arrived in London late, waiting until the day of the match to take a midnight train to town. Battling a headache and unhappy with his hotel accommodations, he headed to the venue to try to catch a nap, disappointed to find his dressing room didn’t even have a comfortable armchair.

He was interrupted by O’Rourke and Rogers, asking if he would allow the release of the wager both wrestlers had posted with a local magazine editor. But Hack was having none of it. Rogers’ confidence may have been wavering, but his own was steadfast.

“You wanted the side bet, you fixed the amount, the public was acquainted with the facts,” he told the men. “…If he loses I’ll take every penny of his side bet.”

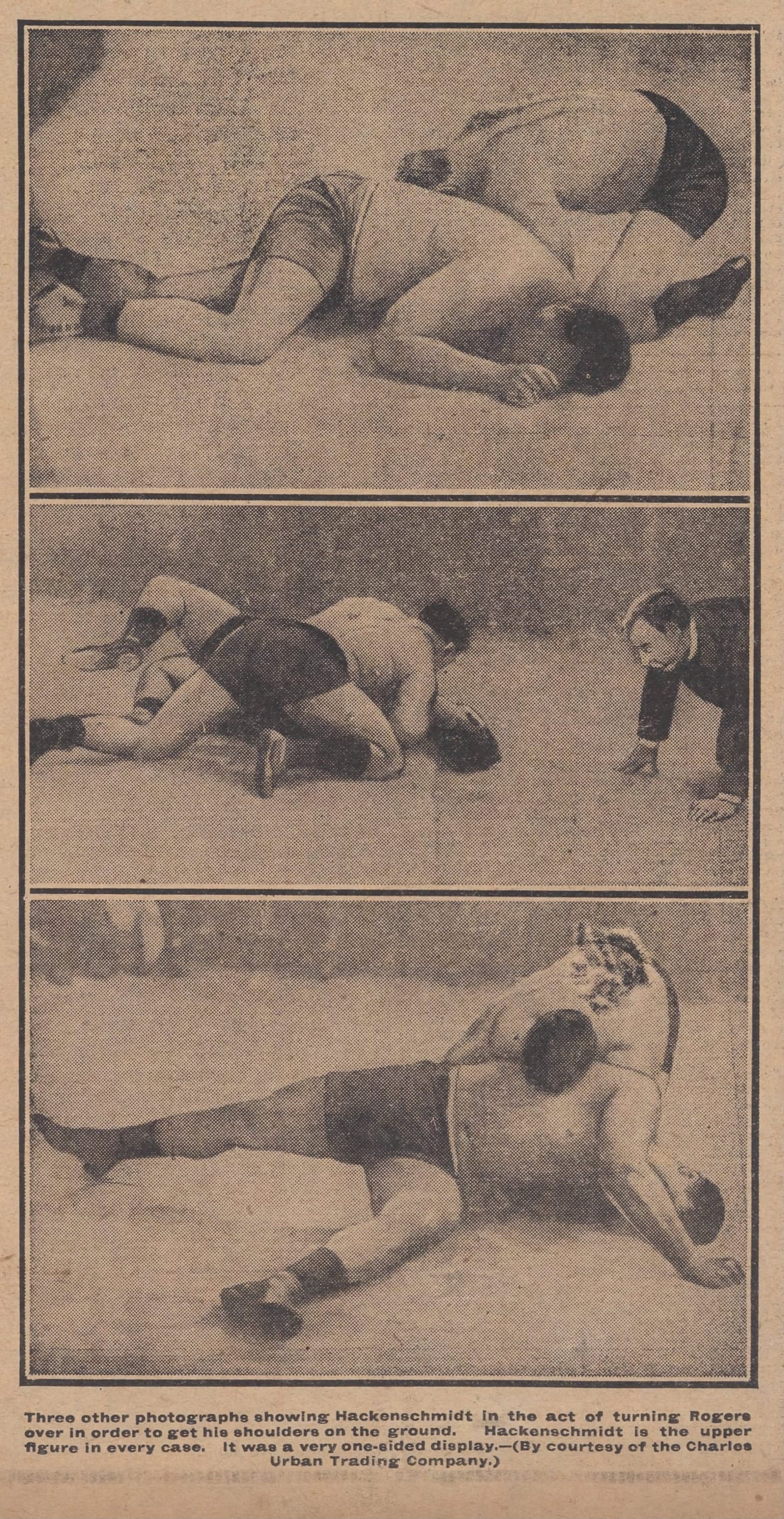

Any lethargy he felt disappeared upon first contact with the enemy. The two collided in front of a packed house, the audience and the referee bespoke in dark colored suits.

“I felt I had to teach him a lesson,” Hackenschmidt wrote, and proceeded to do just that. All told, it was over almost before it started, lasting barely 14 minutes. This time, Hackenschmidt made no concession to the idea of extending the match and giving the crowd a proper show. He was about winning—after all, he had a train to catch and another show that night back in Manchester. According to his Record Book, he wrestled two additional men that evening.

Response to the drubbing was mixed. The Evening Standard called the match a “very disappointing display” complaining “it was at once seen that Rogers had but a poor knowledge of the game.”

The Daily Mirror, instead, focused on the positive, highlighting Hack’s mastery of the big man, wowing at the way he pinned him “as easily as you or I would change an ink-pot from one side of the desk to another, or switch on the electric light…The best man won—and very much the best man too.”

For Rogers, it was the end of the line in England. He couldn’t save face after such a shoddy showing. Soon he was on his way back to America, correct in his premise that all the press would raise his stock; he was almost immediately inserted into a grudge match with Gotch.

For Hackenschmidt, too, the sun was setting on the best days of his career. He also had an upcoming appointment with Gotch—one that would change the course of wrestling history forever.

Jonathan Snowden is a long-time combat sports journalist. His books include Total MMA, Shooters and Shamrock: The World’s Most Dangerous Man. His work has appeared in USA Today, Bleacher Report, Fox Sports and The Ringer.

There was another wrestler in this era named Charles Rogers who also wrestled as “Yankee Rogers.” The two once even met in Montreal, with Joe going over Charles. Frank Gotch earned a win over the other Yankee Rogers the same month Hack took on Joe Rogers. Confused yet?

Rogers claimed to the St. Louis Post Dispatch that after Jeffries’ title fight with Tom Sharkey fans followed him home from the arena “thinking I was the big fellow.”

According to some reports, the big Russian struck Zbyszko repeatedly and performed an illegal takedown, earning a disqualification but keeping his heat. Some things in wrestling never change.

Though both had started as Greco-Roman wrestlers, Hackenschmidt wasn’t interested in a match of that style with Zbyszko, telling his manager Charles Cochran that it was “almost impossible to throw a man of that type did he content himself to act entirely on the defensive.”

Long gone, modern Londoners might remember the location as the home of the original Virgin Megastore.

This tournament, today, is perhaps best known for the participation of Mitsuya Maeda, the Japanese judoka who would later train the Gracie brothers in Brazil.