Reality Is a Work: The Unbreakable Man Who Had to Break

Kenta Kobashi's 2002 Return was Pro Wrestling NOAH At Its Finest

In honor of Jonathan Foye’s new book Freedom and Faith: Pro Wrestling NOAH Beyond the Green Mat, I’ll be writing about some of my favorite moments in NOAH’s history.

When people think about Kenta Kobashi, they often imagine him at the height of his powers, the young bull with the impossibly graceful moonsault. Me? I’m drawn to him in times he looked more human—like this match, from a moment in history where it was unclear whether he’d ever regain his place in the industry.

Let’s posit, for a moment, that almost every heroic comeback story, the kind we’re constantly sold before games across all sports, is a lie we agree to believe. It’s the third act of a movie where the grizzled quarterback with the bad knee throws the winning touchdown, or when the band you loved in high school reunites for one last perfect show, their voices somehow untouched by two decades of cigarettes and bad decisions. We buy into it because the alternative—that no one can truly abate the passage of time, that the knee can only survive so much, that the singer’s voice is shot—is an unsatisfying, realistic bummer.

Pro wrestling, an enterprise built on pre-determined artifice, should theoretically be the ultimate purveyor of the perfect comeback. The hero is supposed to win. It’s written in the code.

Which is why Kenta Kobashi’s return on February 17, 2002, remains such a fascinating cultural artifact. Here was a man who wasn’t just playing a hero; he was arguably the living embodiment of the puroresu ideal, an “Iron Man” forged in the fires of the greatest in-ring decade imaginable.

And then, he broke.

Not figuratively. Literally. For 395 days, his world wasn’t the roar of the crowd but the “cold, white ceiling” of a hospital room.1 His knees, once described as belonging to an 80-year-old, were reconstructed with so much hardware that calling him human felt like a stretch. He was a cyborg held together by willpower and surgical steel, a man whose intense rehabilitation literally changed the color of his hair. He was driven by something beyond mortal, refusing a fate that didn’t include wrestling. The regimented rehabilitation, the long stints in the hospital, the mornings when he simply didn’t want to get up. He did it anyway.

What drove him?

“The feeling that I had to get back in the ring one more time,” he said. “…It’d be a lie if I said it wasn’t hard.”

But feelings can’t help you when you enter the ring against the best in the world, competing against both younger opponents and the ghost of who you once were. The question before the match wasn’t just “What does he have left?” It was, “Is the Kenta Kobashi we remember even in there anymore?”

Wrestling’s Napster Moment

The industry itself was grappling with its own version of the heroic comeback myth—could wrestling resurrect itself through collaboration when the old certainties were crumbling? Pro wrestling was having its Napster moment, the status quo challenged by a new way of thinking. For years, the major promotions existed as walled gardens, profitable, self-contained universes that pretended the others didn’t exist. New Japan Pro Wrestling was the major label, NOAH was the hot new spin-off project.

But the market had changed, and the time-tested ways didn’t work as well as they used to. The rise of Pride and K-1—legitimate combat sports presented with Super Bowl-level pageantry—was the disruptive technology that made the old model feel quaint. The ecosystem was dying. Wrestling was dying.

Suddenly, it seemed evident to all—the walls had to come down.

Antonio Inoki attempted to create a dialogue with the new martial arts leagues, inserting pro wrestlers into organizations that already had the sport’s ethos in their DNA. To say success was mixed was an understatement. Ultimately, his creation and the product of his heart and mind, New Japan Pro Wrestling, decided a different kind of collaboration worked better for them.

The industry leader, New Japan found itself in absolute chaos when its biggest stars, Keiji Muto and Satoshi Kojima, abruptly defected to a nearly-dead All Japan. This was like Pearl Jam and Nirvana leaving Seattle in ‘92 to go start a new scene in Delaware. In a panic, New Japan did the unthinkable: it sought a stronger working relationship with NOAH, its ideological rival.

This wasn’t a cool crossover event for the fans. It was a desperate business decision, which is infinitely more interesting.

The result was Yuji Nagata—a New Japan loyalist to his core—suddenly appearing in a NOAH main event. The multiverse was collapsing. The age of the cross-over was upon us.

Analog Heart in a Digital World

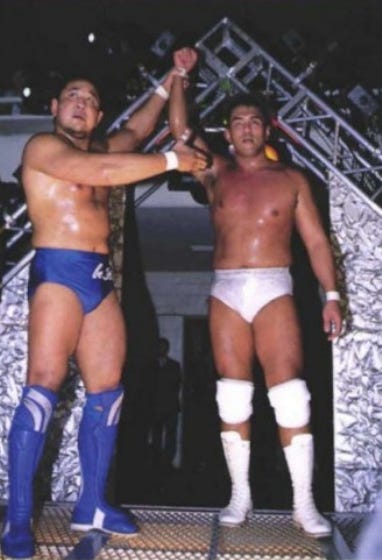

This rapidly changing ideology, one constructed in the what might have otherwise been death pangs for the industry, set the stage for a tag team match that felt like a referendum on wrestling itself. On one side, you had the analog warmth of Kenta Kobashi and Mitsuharu Misawa.2 They were the vinyl record—the sound of 1990s All Japan, rich and powerful, even with the pops and scratches of age and injury. They represented a past that was becoming less commercially viable but remained the critical gold standard.

On the other side was the digital future: Jun Akiyama and Yuji Nagata. Akiyama was the reigning GHC Champion, the man tasked with leading NOAH in Kobashi’s absence.3 Nagata was the outsider, the guest feature on the album, creating a new, hybrid sound. They were cleaner, sharper, and maybe lacked the nostalgic “warmth,” but they were perfectly suited for this new, chaotic environment. Nagata had already been a Guinea pig in Inoki’s failed MMA experiments. Now he was more in his element.

The match asked a fundamental question, one wrestling battles with in every generation as stars fade and Big Bangs occur to put others in their place: In a world demanding newness and crossover appeal, was there still a place for the old gods?

The Unskippable Track That Ends Quietly

Before he even appeared on screen, fans were chanting his name. Budokan Hall4 had sold out quickly when his return had been announced. Those few tickets held back to be sold the day of the show went just as fast. Many who’d turned up to see the match were just as quickly turned away. The place was packed. If they weren’t hanging from the rafters, it was only because the law didn’t allow it.

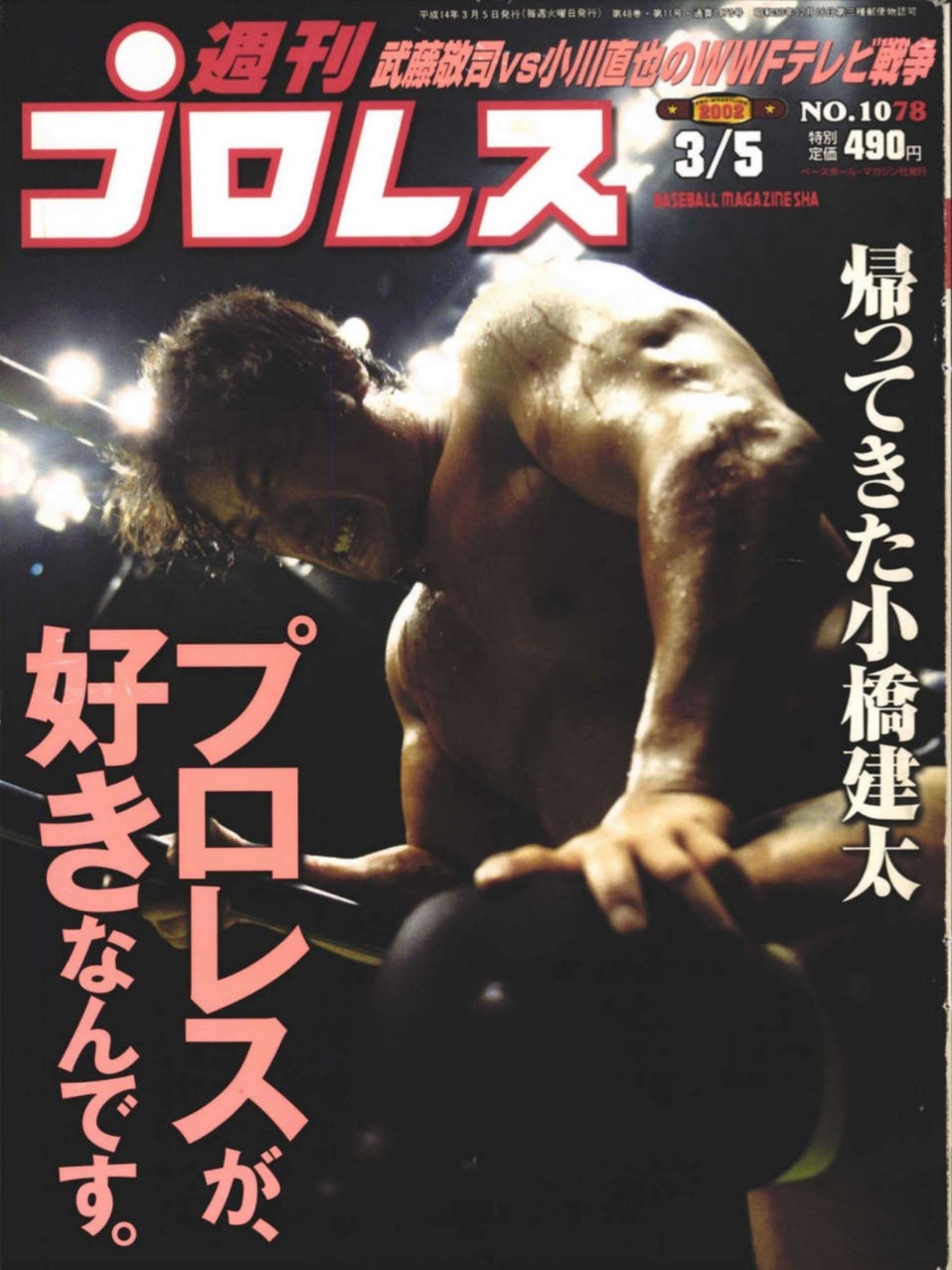

“I always pictured myself walking down the ramp amidst the ‘Kobashi’ chants, telling myself I would definitely return,” he told Weekly Puroresu magazine. “I was so happy that it became a reality.”

The match, by all accounts, was an instant classic. It had that big match feel from the opening bell, that indiscernible, indescribable feeling that it just mattered more than most. It was Kobashi’s return, yes. But it was also a story about four masters of their craft, each attempting in his own way to either remind or convince fans that they were still King Shit.

For 27 minutes, it delivered everything a fan could want: Kobashi’s defiant spirit, Nagata’s smug-technician heel work, Misawa’s stoic strength and protective spirit, and Akiyama’s unsentimental, relentless attack on Kobashi’s surgically-repaired knees, an indication to fans he was willing to do whatever it took to assert himself as the industry’s top wrestler.

It was a stew that combined perfectly, its flavor evoking both childhood comfort food and unexpected spices from an unfamiliar world. At the center of it all, of course, was Kobashi. His strength, as always, was undeniable. Weighing 20 pounds less than he had before his departure, a concession to his ailing knees, he still looked like a powerful force, especially early in the match. It was later, however, that his true genius emerged. His selling made you feel right alongside him, a man telegraphing a universe of pain while refusing to submit to it.

And then came the ending. The part of the script where the hero typically overcomes the odds. But NOAH made a different, more artistically daring choice. They chose reality. After a furious closing sequence, Akiyama hit his finisher, the Wrist-Clutch Exploder, and pinned Kenta Kobashi. Clean.

The hero lost.

In a lesser promotion, this would be a catastrophic booking failure. But here, it was a stroke of genius. It was the logical finish. The most compelling lie is one that feels true, and the truth is that a man who hasn’t competed in over a year shouldn’t beat the reigning world champion in his prime.

“It’s not easy,” he said after the match. “It was tough and it was heavy. The result in the ring is everything. It’s frustrating, but this is reality.”

The loss validated Akiyama’s title reign and respected the intelligence of the audience.5 It was the pro wrestling equivalent of the shocking, unceremonious ending of a 1970s neo-noir film—it’s not what you wanted, but it’s something you knew in your heart was right.

The match was, according to Weekly Puroresu editor Masayuki Sato6, a triumph not just for Kobashi and NOAH, but for the very concept of pro wrestling itself, embattled but far from dead:

Right now, it is said to be an era where it’s difficult to feel pride in pro wrestling. Indeed, pro wrestling is under external pressure in various ways. But as long as there is a man like Kenta Kobashi, there is no reason for fans to lose confidence in wrestling. His fight, filled with an endless love for the sport, heals a pro wrestling wounded by outside forces and gives courage to the fans.

Here, I want to write about the influence Kobashi’s return had on NOAH. His partner, Mitsuharu Misawa, and his opponent, Jun Akiyama, clearly had a chemical reaction. Akiyama, after Kobashi’s absence, had led NOAH from the front. But there were surely times when Akiyama couldn’t just be Akiyama. To energize the promotion, he had to make sacrifices, focusing his energy on creating themes for tours and developing younger talent. But the moment Akiyama can truly be himself is when he is facing none other than Kobashi. It is Kobashi who ignites Akiyama’s cool heart.

It was a statement that this wasn’t just a story—it was a sport. In its own way, it blurred the lines between the two as much as Inoki ever had.

The Start of a New Chapter

The fans weren’t asked to buy into another heroic comeback fantasy. They were witnessing something even more ephemeral, something truly glorious—a man whose authenticity transcended victory or defeat.

The comeback, in theory, was a bust. Except it wasn’t. Because as Akiyama and Nagata stood tall, the 16,500 fans in the Budokan began to chant. Not for the winners, but for the loser.

“Ko-ba-shi! Ko-ba-shi!”

They weren’t cheering for the result; they were cheering for the man. They saw the effort, they saw the heart, and they affirmed their belief in him, win or lose.

The immediate aftermath was cruelly ironic. Kobashi re-injured his knee in the match and was told he’d need another year off. Being a superhuman, he was back in five months. But it would be more than a year before he competed once again for singles gold.

It turned out the loss and the subsequent injury weren’t the end of the story. It was the prologue. It was the quiet, acoustic B-side that set up the explosive, chart-topping A-side to come. Fans, one Weekly Puroresu writer said, were with Kobashi because of how he responded to adversity, not because he was invincible, unbeatable:

The story of Kenta Kobashi has always been a story of climbing back up. We, the fans, have gone wild for Kobashi as he fought his way up, cheered him on, and in the end, were always moved. That’s why we believe he will overcome this harsh reality.

This painful, imperfect return was the narrative foundation for his 735-day GHC Championship reign, an epic run that would define NOAH’s golden era and go down as one of the greatest in the history of the business. He had to lose. He had to prove he was breakable one last time before he could become the “absolute champion”. He had to fail to give his eventual success meaning. When asked why he endured all of it—the surgeries, the pain, the heartbreaking loss—Kobashi’s answer was the simplest, and therefore the most profound, explanation possible.

“I just love pro wrestling.”7

Here was the truth that made most other comeback stories feel like hollow theater. The crowd’s chant wasn’t for mythic invincibility—they were witnessing gaman. Kobashi was enduring the unendurable with quiet dignity. What drove him through 395 days of hospital ceilings and learning to walk again wasn’t the promise of inevitable victory.

It was the love of the craft itself.

It was fighting spirit.

This was ganbaru—the cultural imperative to persist despite failure.

Kobashi’s humility in defeat revealed a more authentic heroism than any scripted triumph could ever provide. The story we agreed to believe became unnecessary when we were presented with a narrative conceit even more rare than a good lie—something real.

Jonathan Snowden is a long-time combat sports journalist. His books include Total MMA, Shooters and Shamrock: The World’s Most Dangerous Man. His work has appeared in USA Today, Bleacher Report, Fox Sports and The Ringer. Subscribe to this newsletter to keep up with his latest work.

The “White Ceiling” is a powerful and common metaphor in Japanese storytelling for sickness, hospitalization, and despair. It effectively contrasts the bleakness of Kobashi’s recovery with the vibrant, colorful world of the pro wrestling arena.

An enduring legend, Kobashi’s senior, and the founder of Pro Wrestling NOAH. He was a multi-time champion and one of the most respected figures in the industry.

A younger, brilliant wrestler who was seen as the inheritor of the “King’s Road” style. At this point, his story was that he was carrying the company while Kobashi was away. The match is framed as him “testing” his returning senior.

Nippon Budokan (日本武道館): This isn’t just any arena. It’s a sacred venue in Tokyo, initially built for judo in the 1964 Olympics. For pro wrestling, holding a major show there signifies that a promotion is at the top tier. It’s a hallowed hall with immense history.

There is an implicit story of seniority (senpai-kōhai relationship). Misawa and Kobashi are the established legends (seniors), while Akiyama is the younger ace (junior) who must prove he can carry the company. Akiyama defeating Kobashi isn’t just a win; it’s a statement that he belongs in the position that Kobashi left behind.

Sato writes that he considers Kobashi a “classmate” in the industry because they both started their careers around the same time. When Kobashi was a rookie, Sato was a junior reporter who served as his beat reporter, covering his early matches very closely. Sato recalls telling a young Kobashi that he would one day be the one to write the story when Kobashi finally won the prestigious Triple Crown Championship. He expresses that it’s a “deeply moving” experience for him, now as editor-in-chief, to feature the beginning of “Kenta Kobashi, Chapter Two” on the magazine’s cover.

「プロレスが、好きなんです。」 (Puroresu ga, suki nan desu.) - “I just love pro wrestling.” This is a simple, powerful, and deeply personal statement from Kobashi. In Japanese, this phrasing feels heartfelt, like a confession. It explains his motivation for enduring a brutal recovery.

Akiyama pinning Kobashi in this match was arguably more important in terms of establishing him as a main event star than him beating Misawa for the GHC title a few months before in a match that, when you watch it, practically screams of Misawa doing everything in his power to get Akiyama over and Akiyama not really holding up his end. (IMO, of course)