Blood and Bones: The Ballad of Jon Jones

The UFC Great Leaves a Complicated Legacy in his Wake

PART I: A Boy Made for Violence

You start with the blood. With Jon Jones you have to. The genetics. A gift from some laughing, careless god. His father, Arthur, was a pastor, a man who lived in a world of scripture and Sunday service, trying to raise his children by the book. His mother, Camille, a nurse, a woman who mended what was broken. They tried to build a house of faith, a house of order. But the boys they raised were built for something else entirely. For chaos. For violence.

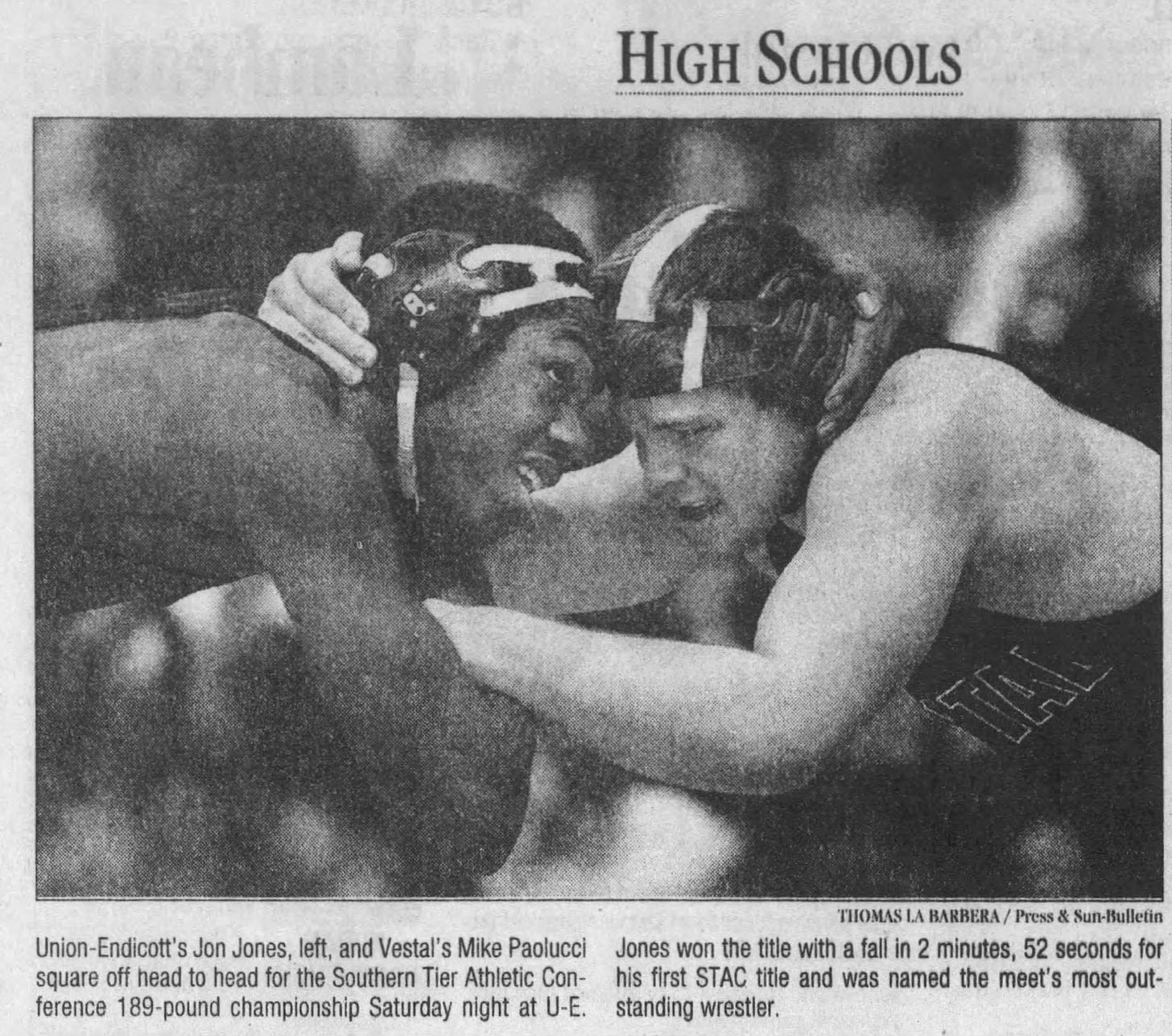

Two of them, Arthur and Chandler, grew into mountains of muscle and speed, titans made for the NFL, a sport of controlled, strategic brutality. And then there was Jon. The middle one. “Boney,” they called him. All limbs and awkward grace. Couldn’t catch a football to save his life. Couldn’t dribble a basketball. A failure at the games of men. But his calling was different. His calling, it turns out, was wrestling. In the basement, on a mat his father brought home, he grappled with his brother Art, already a giant at 260 pounds. And in that struggle, one on one, he found his language. Other boys his size felt like nothing after that.

Puny. Breakable.

MMA was not a life he chose, not really. Not in the way a man chooses a trade. It chose him. He dropped out of college, a girl pregnant with his first daughter, another on the way with his fiancée, Jessie. Drowning. He worked as a bouncer for $60 a night, a lanky kid with a smooth face and warm eyes, learning the ugly geometry of bar fights. He was about to become a janitor at Lockheed Martin when a friend reached out on Facebook. A chance to fight for quick cash.

You have to be realistic about these things. When you’re drowning, you don’t ask what the rope is made of. You just grab.

And he was a natural. Of course he was. But not in the way of the old masters, the ones who spend years in a dojo, learning discipline, learning respect, absorbing a philosophy. Jones had no time for philosophy. He had no need for it. He learned by watching. He’d go to the gym, learn the basics, then go home and continue his training on YouTube. He watched anime fight scenes. He watched Japanese pro wrestling. He saw a move, something that looked like it worked, and he would translate it into the real. Into violence that was horribly, beautifully effective.

There was no sensei, no grandmaster passing down ancient wisdom. Just a kid with a dial-up connection to the world’s collected brutality. He saw a spinning elbow, he threw a spinning elbow. He saw a suplex, he threw a suplex. He saw a path to victory, and he took it. He was a revolutionary, they said. A prodigy. But what he really was, from the very beginning, was a man who understood the value of a shortcut. A man unburdened by rules, by tradition, by the way things are supposed to be done.

It was the source of his genius in the cage. It would be the source of his ruin outside of it.

The same mind that saw a spinning backfist on a grainy video and thought, I can do that, was the same mind that would later see a fast car and think, I can drive that, drunk or not. The same mind that would see a line of cocaine and think, Why not? He was a man who saw only the result, never the cost of the journey. A man born to fight, trying to live in a world with rules he was simply not wired to understand.

What Freedom Looks Like

Freedom. That’s what they call it when they let a predator out of its cage. Jon Jones arrived in the UFC on two weeks’ notice, a last-minute replacement, and dismantled Andre Gusmao with a casual ease that felt like contempt. You could see it then, if you were looking. The future.

One writer who traveled across the country to sit cageside at each UFC event saw it immediately. He was cageside for Jones’s second fight, against Stephan Bonnar, a man who was supposed to be a veteran test. Jones treated him like a toy. A German suplex. A spinning elbow that Bonnar thought was a bottle thrown from the crowd. “I had seen the future that night,” the writer said. A future of beautiful, creative violence.

Okay that writer was me. I was on the Bones bandwagon early, talking about him as the best fighter this young sport had ever seen back when that was an outlier opinion and not, well, obvious. There had never been another fighter quite like young Jon Jones.

And then came the first sign that the rules were merely suggestions. A fight against Matt Hamill, a deaf wrestler with a heart bigger than his skillset. Jones was destroying him. A mauling. An epic beatdown. And then he was disqualified. For what? For being too violent. For using illegal 12-to-6 elbows, a rule so specific, so arcane, it’s like a law against breathing too hard. He didn’t lose to Hamill. He lost to the rulebook. It was his only official loss, and it was a perfect prophecy.

The only thing that could ever beat Jon Jones was a set of rules he refused to acknowledge.

He became the youngest champion in UFC history at 23. He didn’t just beat the legend Mauricio “Shogun” Rua; he dismantled him. Took him apart piece by piece, like a bored child pulling the wings off a fly. The fight was hard to watch. That’s how you know a legend is being built.

The duality of the man was cemented on that very day. In the morning, he was a superhero, chasing down a robber in the streets of Paterson, New Jersey, a real-life champion of the people. By nightfall, he was a king, the belt around his waist. He was the good man his father raised. He was the hero everyone wanted.

For a moment.

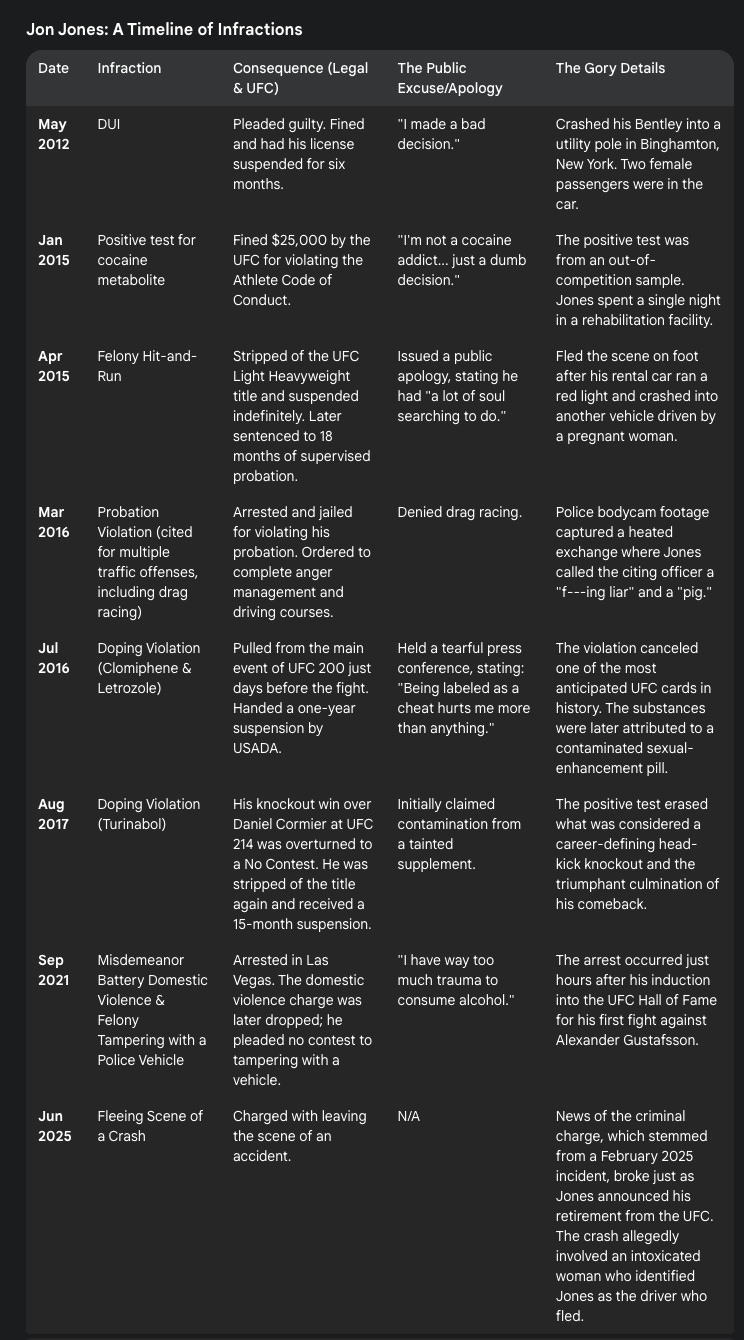

A few months later, he wrapped his new Bentley around a utility pole in Binghamton, New York. He was drunk. He had two young women in the car with him, neither of them his fiancée. He pleaded guilty. The mask slipped. The brand cracked. The brand. That’s what it was all about. He was the first UFC fighter to sign a worldwide deal with Nike. He was on Forbes’ “30 Under 30” list. He was the clean-cut, Christian role model. He was the face of the sport.

He was a lie.

A beautiful, profitable lie. A lie he told the world, and a lie he almost certainly told himself. He wanted to be the good man. He wanted the adoration, the money, the clean legacy of a Georges St-Pierre. But the instincts that made him a killer in the cage—the aggression, the ruthlessness, the sheer, animal impulse—were the same instincts that made him a disaster outside of it. He was a man at war with his own nature. And his nature was winning.

PART II: A Bad Enemy to Have

A king needs enemies. At least in the world of fantasy fiction, of Martin and Abercrombie. A king is defined by the quality of his challengers, by the bodies he leaves strewn at the foot of his throne. Jon Jones, in his prime, had the best enemies a king could ask for. Each one a different facet of his own dark soul. Each feud a different kind of cruelty.

First, there was the brother, Rashad Evans. They were teammates at the Jackson-Winkeljohn gym in Albuquerque, friends, or something like it. Jones was the prodigy, Evans the former champion. He taught the younger fighters how to dress, how to move through a world of hustlers, how to handle the fame. When Evans was injured, the UFC offered Jones a title shot against Shogun Rua—the shot that was supposed to be Rashad’s. Jones took it. Of course he did. A man who worships himself has no room for loyalty. Evans saw the betrayal for what it was and left the gym that had become his home. The fight, when it finally happened, was a cold and clinical execution. Jones picked his former mentor apart, a passionless display of dominance. It wasn’t a fight; it was an exorcism. The final, brutal severing of a bond he never truly valued.

Then there was the legend, Quinton “Rampage” Jackson. This was not about betrayal. This was about bullying. This was about a young lion toying with an old one, just to see him break. The fight was a masterclass in methodical cruelty. He used his impossible reach to keep Rampage at a distance, poking at him with long kicks to the knee, a technique designed not just to win, but to maim. He stuck his fingers in Rampage’s face, a constant, irritating threat of an eye poke. Then, when the legend was tired, hurt, and frustrated, Jones took his back and choked him out. It was the first time Rampage had ever been finished in the UFC. Jones didn’t just beat him; he humiliated him. He delighted in every dirty trick of war, that there was no line he wouldn’t cross for an advantage.

But his greatest rival, his truest enemy, was Daniel Cormier. In Cormier, Jones saw a warped reflection of everything he was supposed to be. Cormier was the Olympian, the respected captain, the man who did everything the right way. He wouldn’t fight his own teammate, Cain Velasquez, out of loyalty—the very loyalty Jones had spat on with Evans. Cormier was the authentic article. And Jones, a phony, hated him for it with a purity that was almost religious.

Their feud wasn’t about a title. It was about identity. It started, as these things often do, with a misunderstanding. A clumsy attempt at alpha-male bonding from Jones backstage in 2010 that Cormier took as a profound insult. From that tiny seed of resentment grew a forest of pure, uncut hatred. It exploded in 2014, at a press conference in the lobby of the MGM Grand. A staredown became a shove, a shove became a punch, and suddenly the two best light heavyweights on the planet were tumbling off a stage, a tangle of limbs and fury amidst screaming PR reps and scattered furniture.

But the real truth, the ugly, naked truth, came out later. On ESPN, after an interview, a hot mic caught the moment the mask didn’t just slip, it shattered. The cameras were supposedly off. The polite, Christian role model was gone.

“Hey pussy, are you still there?” Jones hissed across the satellite feed to Cormier.

Cormier, for his part, was just as raw. “I wish they would let me next door so I could spit in your fucking face.”

And then came the line that defined the man. The line that laid his soul bare.

“You know I would absolutely kill you if you ever did something like that, right?” Jones said, his voice low and cold. “I would literally kill you”.

There it was. Not a fighter. Not an athlete. A killer. The villain Cormier always said was lurking beneath the surface.

The fights themselves were almost an afterthought, two perfect, bitter tragedies. In the first, Jones dominated Cormier, out-wrestling the wrestler, breaking his will over five rounds. A masterpiece. A week later, the news broke: Jones had tested positive for cocaine metabolites before the fight. The victory was forever tainted. In the rematch, he was even better. He knocked Cormier out with a spectacular head kick, a moment of shocking, final violence. He stood over his fallen rival, weeping, the belt back around his waist. It was the defining moment of his career. And then it was erased. He had tested positive again, this time for the steroid Turinabol. The win was overturned. The belt was stripped. Again. He could beat Daniel Cormier. He could break him, knock him unconscious, make him weep. But he could never truly defeat him, because he could never defeat himself. He was his own worst enemy, and it was a fight he never, ever won.

For Jon Jones, life was divided into two extremes. One was in the cage, a place of controlled action, of exquisite pain inflicted on others. The other was the world outside, a place of uncontrolled, chaotic pain inflicted on himself. A long, grim, repetitive march from one self-inflicted wound to the next. You get tired of it. But the road goes on.

The work he did on himself was a masterpiece of destruction, a litany of sins so long and so varied it bordered on the artistic. Mistakes lead to learning with most men. But some men harden. Jones just kept getting up, finding new ways to fall down.

The list of his transgressions is a monument to a man who could not be controlled, not by others, and certainly not by himself. But it’s also a monument to something else. To a system that needed its king, however tarnished his crown. Each time he fell, they picked him up. The UFC fined him, stripped him, suspended him, and then, when the time was right, they reinstated him. The Nevada State Athletic Commission saw his positive test for cocaine before the first Cormier fight and shrugged. It was “out-of-competition,” they said. The fight, and the millions of dollars it would generate, went on. He learned the most dangerous lesson a man like him can learn: that consequences are for other people. That if you are a big enough star, if you generate enough money, the rules are not iron chains. They are cobwebs, easily brushed aside. His self-destruction was not a solo act. It was enabled, encouraged, and ultimately rewarded by a world that valued his violence far more than his virtue.

PART III: The Magic Man

There’s magic, and then there’s the slow grind of reality. In his early days, Jones was all magic. A blur of spinning techniques and impossible athleticism. Of choking Lyoto Machida, then dropping his limp body like a bag of trash, putting the other man’s “era” in the dustbin of history. But after the wars, after the scandals, after the endless cycle of sin and hollow repentance, the magic began to leak out of him. He was still the king, but he was a king who seemed bored by his own crown.

The change came against Alexander Gustafsson. September 2013. UFC 165. Jones was the unbeatable champion, the prohibitive favorite. Gustafsson was just another challenger. Jones, by his own admission, took the fight lightly. His coaches said the opponent didn’t “excite him”. And for five rounds, the unexcited king was dragged into the deepest, bloodiest water of his career. Gustafsson cut him, took him down, and pushed him to the absolute brink. Jones escaped. He won a decision, the Fight of the Year, but something was broken that night. The aura of invincibility was gone. He looked human. He looked, for the first time, like a man who could be beaten.

That fight became the template for the rest of his reign at 205 pounds. The unchecked aggression, the sheer, joyful violence of his youth, was gone. It was replaced by a cold, calculating intelligence. A man managing risk. He was no longer a berserker. He was a general, using his absurd 85-inch reach like a row of pikes to keep the enemy at a safe distance. He became a fighter who was happy to win a decision.

And those wins still came— but they were narrow, often controversial. He scraped by Thiago Santos. He edged out Dominick Reyes. The finishes dried up. The magic was gone.

He tried to get it back. He got serious in the gym, they said. He started powerlifting, transforming his lanky frame from “Bones to Meat”. I went to see where he was building his new body, one of many trips to Albuquerque, realizing this was a rare chance to witness a legend in real time. He got stronger, but he didn’t get more dangerous. The fire wasn’t there. His coaches knew it. “I don’t think anyone can beat Jon Jones but himself,” Mike Winkeljohn said. Greg Jackson talked about his “fight computer,” his ability to download data and adapt.

They were describing a machine, a problem-solver. Not a killer.

What they missed, what everyone missed, was that the magic was never just about talent. It was an alchemy of talent and malice. He needed a Cormier. Without a great rival to fuel him, he was just a man going through the motions. A predator with no worthy game to hunt may be full, but he’s bored. And a bored predator is a lazy one.

He was still the best. But he was no longer great.

Part IV: The End

The end, when it came, was just like the man himself: brilliant, frustrating, and ultimately, a profound disappointment. After three years away from the sport, stewing in his own troubles, he decided to finally become a heavyweight. He came back at UFC 285 and reminded everyone what a monster he could be. It took him less than three minutes to wrap his arm around Ciryl Gane’s neck and squeeze the fight out of him, becoming the heavyweight champion of the world. Or, at the very least, the UFC’s version of the same.

“It took less than three minutes in the cage for Jon Jones to remind the MMA world just who the fuck he is,” as one writer (okay, also me) put it.

For a moment, the magic was back.

He cemented his legacy, or so he thought, by beating the ghost of Stipe Miocic, an aging legend whose name would look good on the resumé. He could now claim to be the best in two weight classes. The GOAT debate, he figured, was over. He was the best to ever do it. He could say it himself, bah’ing like a goat in the cage, because it was true.

And then he stopped. Just like that. The division had new monsters. Young killers. There was Francis Ngannou, a man with hammers for hands who had also beaten Miocic and never lost his belt. Tom Aspinall, the slick, fast interim champion. Real fights. Dangerous fights. The kind of fights that build a legend. Jones wanted no part of them. He said Aspinall didn’t “excite him”. He said it was pointless, because if he beat him, there’d just be another guy after that. He said it all, except for the truth.

The truth is, you have to be realistic. And the reality was that he was afraid. Not of the men themselves. He’d fought big, tough, savage men his whole life. He was afraid of the one thing he couldn’t control: the outcome. He was afraid of losing.

A single loss would tarnish the brand, complicate the legacy. And his legacy, in the end, was all he cared about. He treated it not as something to be forged in the fire of competition, but as a public relations problem to be managed. He chose the safe path. He avoided the risk. The man who was fearless in the face of laws, rules, and common decency, was terrified of a fair fight he might lose.

It was a Mexican Standoff, in the end. The kind where everyone has a gun pointed, and everyone ends up shot. Jones, the unpredictable king, against the UFC, the monolithic empire that had grown fat and indifferent on its own success. There was a time when a promoter not making the biggest fights possible was suicidal. A quick death. But this new beast, TKO, it was different. It had zero incentive to make the fights the world wanted to see. Jones vs. Ngannou. Jones vs. Aspinall. Fights worth millions of dollars, left to rot on the vine. The old ways were dead. Lorenzo Fertitta would have closed the deal, convinced Jon to dare to be great. But the new masters didn’t seem to know how.

As great as he was in the cage, much of the discussion about Jones will center on everything but sports. It’s a bitter joke, when you think about the men he kept around him. Good men. Men worth admiring. His father, the pastor, trying to build a house of faith. His coach, Greg Jackson, a philosopher of violence, a man who saw fighting as a math problem to be solved, who tried to impose order on Jones’s chaos. Brandon Gibson, the loyal corner man, the brother who was there to talk him through his demons, to pick him up when he fell, time and time again. Even Georges St-Pierre, the perfect champion, the man with the clean legacy Jones so desperately wanted for himself, was there in the same gym at times, a living example of how to be great without being a monster.

They flocked to him, these good men, drawn by the blinding light of his talent. They saw the raw clay and thought they could mold it. But Jones was a sponge for technique, not for character. He could watch a man throw a kick and own it in an instant, but he could watch a man be decent his whole life and learn nothing at all. He took their knowledge, their strategy, their loyalty, and gave back only victories and shame. He was a student who aced every test and failed every lesson.

His retirement was a fittingly pathetic affair. No grand announcement. Just a late-night phone call to Dana White. The king abdicating his throne with a whisper. And then, in the most perfect, ugly, and inevitable final scene, the news of his retirement was immediately overshadowed by another police report. Another car crash. Another instance of him fleeing the scene, leaving an intoxicated, partially undressed woman behind. The cycle, unbroken.

He was our spoiled genius, a petulant boy king who kept threatening to finally grow up but never really did. He was the greatest threat to his own ambitions, the only man who could ever truly beat him. He was arguably the best fighter to ever do it. He was also a jerk, a bully, a cheat, and sometimes a bad man. He was all of those things at once. Life can be complicated like that.

He could have done more. He should have done more. He had the talent to erase all doubt, to stand alone on the mountain top, undisputed. But in the end, he couldn’t get out of his own way. He pissed away years, he tarnished his own name, he made it impossible for anyone to truly love him.

And yet. And yet.

After all that, after every self-inflicted wound and every squandered opportunity, he is still there. Still in the conversation. Still, for many, the best to ever do it. And that, more than any victory, more than any title, tells you everything you need to know about the talent he possessed. A talent so vast, so blinding, it makes the man he could have been, the man he should have been, the greatest tragedy of all.

Jonathan Snowden is a long-time combat sports journalist. His books include Total MMA, Shooters and Shamrock: The World’s Most Dangerous Man. His work has appeared in USA Today, Bleacher Report, Fox Sports and The Ringer. Subscribe to this newsletter to keep up with his latest work.

It's absurd he's probably the best fighter we've seen in MMA thus far, and *still* somehow a what-if story. Imagine what his legacy would've been had he stayed out of trouble. It's a classic tragedy, a great man undone by his own hubris.

Another excellent profile. Great job!