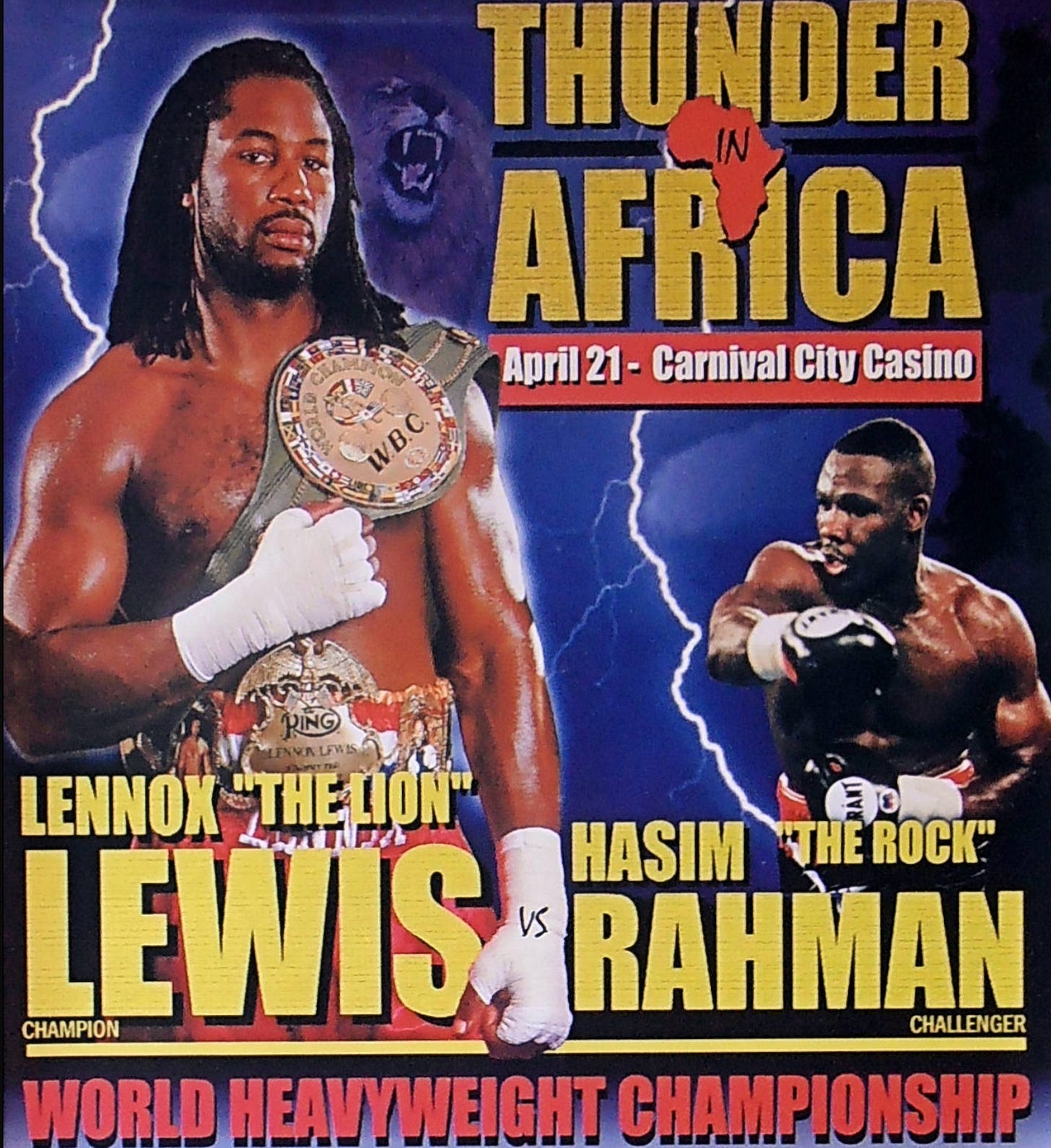

Upset of the Decade: The Night Hasim Rahman Lit $100 Million on Fire in South Africa

22 Years Ago Yesterday

Last night Gervonta Davis stunned Ryan Garcia with a punch to the liver to become the self-proclaimed “face of boxing.” But he was far from the first fighter from the mean streets of Baltimore to strike it big on pay-per-view.

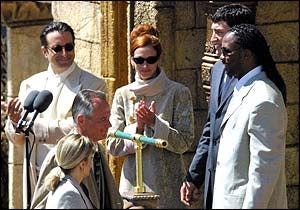

It was supposed to be the fight before the fight, an event so small that no regular boxing media bothered to make the trip. Lennox Lewis was going to fly into South Africa at the invitation of Nelson Mandela, dispose of an unknown challenger and move on to the fight he’d been after for years—a $100 million mega-bout with a thoroughly washed up Mike Tyson.

Lewis was not especially concerned about Hasim Rahman heading into their title fight on April 22, 2001. Truth be told, not many in the boxing world were. Rahman, a raw heavyweight with two losses already dotting his ledger, was seen as a stay-busy opponent, a way for Lewis to pocket a small fortune while waiting for the larger one to finally come to fruition.

Sure, his trainers had to go through the motions, unconvincingly claiming the possibility of disaster loomed in the form of a clubbing Raham blow. But they could hardly keep a straight face while doing so. In many ways, Lewis’ estranged promoter Panos Eliades spoke for many in Lennox’s circle in an unusually candid interview with the Evening Standard in the months leading into the fight, back when the Lewis camp was in the process of choosing between Rahman and the equally unexciting David Izon:

“Lennox,” the promoter said, “could take them on with one hand tied behind his back. Both of them, on the same night.”

Rahman was certainly aware of how he was perceived, a 20-to-1 underdog at one point. He just refused to believe he was a no-hoper. A product of the West Baltimore streets, Rahman had become a legend on his block by dropping three grown men when he was just 14 years old. Soon he was an enforcer keeping a watchful eye on “the Store”, so called because everything was for sale on West Lafayette Avenue.

Sometimes the crew would make 100 grand on a good day. With that much cash on the line, the young renegade had plenty of work. Mostly conflicts went his way. He was big, strong and mean—but no one survives the life unscathed. In his teen years he was shot, stabbed and badly scarred in a car accident. By his own admission, death or prison were dueling to see which would be his future.

“For every success story,” Rahman said, “I can tell you 50 people who didn’t make it.”

Instead, he ran into local boxer Lou Butler one night and changed his entire life. Butler challenged the young tough to an exchange of body punches. When Rahman held his own, Butler sent him to trainer Mack Lewis across town, telling the young man he had a million bucks worth of potential. Just eight years later, Rahman had done him $500,000 better—his purse for the Lewis bout was a milly and a half.

While Lewis luxuriated in Las Vegas splendor, even filming a scene for the crime caper Ocean’s 11, Rahman was grinding away in New York’s Catskills Mountains, preparing for a fight nearly 6000 feet above sea level. He lived in South Africa for more than a month, becoming acclimatized to the people and the environment.

Rahman and his camp saw the contest as a war, with the fight being merely the most important battle. They wanted to win everywhere. Every press conference, every training session, on the streets of South Africa making their case to the people, wherever the fighters were engaged, Rahman wanted to emerge victorious.

Most amazing of all, despite his much smaller profile in the media, he was managing to pull it off. When he first got off the plane in Johannesburg, the waiting media didn’t even recognize him, surrounding instead a muscular missionary on the same flight. But, by the night of the fight, he had ingratiated himself with the people, as open and accessible as Lewis was haughty and distant. It wasn’t enough to convince bettors to go in on the unknown. But it did convince someone closer to home—Rahman’s manager Stan Hoffman, who claimed he bet a million bucks on his fighter to shake up the world.

“I've had 31 world champions as a manager and I've never predicted a knockout —not once,” Hoffman told BBC Radio. “I believe in this case, if there's a war - and we hope there is one - then Lennox will be knocked out.”

Ironically, due to his subsequent popularity there, Rahman was initially opposed to moving the fight to South Africa, borrowing a phrase from Don King—he’d fight “only in America.” But those 1.5 million very American reasons changed his mind. It was a once-in-a-lifetime payday Rahman, a father of three, couldn’t afford to turn down. He thought he’d made it when he moved out to the suburbs of Bel Air, Maryland. Money like this meant he’d never have to go back.

Lewis, critics believed, should have spent more time preparing for the mountain air and less time enjoying the celebrity status that came with the heavyweight championship, even in its depleted state. The champ tired quickly of that particular media narrative, rejecting outright concerns expressed by the likes of Los Angeles Times reporter Steve Springer, who presciently compared the vibes surrounding the bout to Tyson-Douglas.

"I don't believe everything the scientists say about altitude,” Lewis told the press. “It will be no problem. (Rahman) shouldn't worry so much about the altitude. He should just worry about me."

Despite the champion’s obvious disinterest and the shades of Tokyo that experienced observers were starting to notice everywhere, Lewis remained a 15-to-1 favorite in the casino where the fight was held. While some fighters would use that kind of disrespect as a chip on the shoulder, motivational fodder to inspire greatness, Rahman took it all in stride. He wasn’t focused on what Lewis was doing or what critics had to say. Instead, his attention was firmly fixed exclusively on the goal in front of him—becoming boxing’s heavyweight kingpin.

“Me myself, being a boxing guy, I wouldn’t have picked me,” Rahman admitted after the fight to The Ring’s Nigel Collins. “That’s why I couldn’t have held it against anybody. Based on seeing my previous fights, I wouldn’t have picked me. That Hasim Rahman who people have seen wouldn’t have had a chance against Lennox, so I had to take it to another level.”

Lewis, who came in at the heaviest weight of his career, called Rahman a “piece of meat that I will play with.” Instead, the champion, in the fourth title defense of his undisputed reign, found Rahman too big a bite to chew.

Rahman established an early lead, attacking the first round with gusto. As the minutes passed, however, Lewis displayed his class. He was the better, more experienced boxer, in the midst of his 15th title fight. It was Rahman’s first time competing for all the marbles, but if he was nervous, it never materialized on his scarred face. He was losing the rounds, but never out of the fight, focused on landing a bout-changing right hand. He was stronger than ever, bench pressing more than 400 pounds for reps in the gym and confident he could do damage if he could find his way past the champion’s solid defense.

“The whole time I was here I felt a sense of calm and confidence,” Rahman said after the fight. “I didn't get nervous, not one time since the fight was made. I wasn't even nervous in the dressing room.”

A cut over his left eye, caused by a clash of heads in the fourth round, distracted Rahman for a time. The challenger pawed at his face repeatedly, hoping to clear his vision he would say later, much to the chagrin of announcer George Foreman.

“If you start to bleed,” the former champion proclaimed, “so what?”

Lewis, for his part, seemed bored with the fight, furious about how the entire event turned out. When he’d accepted Mandela’s invitation he had assumed the fight would be in an outdoor arena in front of tens of thousands of Black Africans. Instead, less than a decade after the end of apartheid, the local promoter had booked the bout for the Carnival City Casino in an arena that held fewer than 7,000 seats, most of them occupied by rich white men from the former ruling class.

“The promoter did not want the masses to see me box,” Lewis said. “He wanted to keep me enclosed.”

Although his face remained stoic, even during an entrance that included African dancers and an ode to Mandela, you could read Lewis’ disdain for his opponent in his actions. Normally almost impossibly patient and careful (some would say boring), Lewis began looking for his piston-powerful right hand without setting it up with a jab first, wading in with his hands down, looking for a quick finish instead of systematically breaking Rahman down as was his usual practice.

It was almost as if he was daring disaster, providing his opponent a pathway to victory that Rahman could have never carved out for himself. But one thing the Rock could do was target an opening with a right hand—and he cracked Lewis with a solid one in the fifth round. The champion just smiled in response. But it was his retreat into the ropes that was more telling. Rahman, worried just seconds before about his own cut, smelled blood and pounced, a right cross connecting perfectly with Lewis’ chin.

Ten seconds later, it was all over.

“I can't believe it,” Lewis said. “I just can't believe it. I felt fine. I was going about my work nice and comfortable.”

In the broadcast booth, HBO’s team, seemingly somnolent by the 5 AM local start time, attempted to rise to the moment. Foreman, ever the patriot, proclaimed it was once again possible to sing the national anthem. An American was sitting on boxing’s throne.

Larry Merchant, who struck out with “Crumble in the Jungle” in his first attempt at memorializing the gargantuan upset, eventually struck gold, eulogizing Lewis as a former champion who “just drowned in Ocean’s 11.”

“Lewis was over-confident,” former champion Foreman later told The Guardian, “and I think it's a reflection on his trainer. If you bring a guy into training camp and he's not in shape, then don't bring him down to the fight. It was a case of hands down, walking forward, disregarding a man you have seen films of but all you look at is the clip where he was knocked out and you try to replicate that. It happened to me when I fought Ali in '74. I thought I was going to knock him out in two. Instead my hands are down, my head is up and I end up losing.”

The trainer in question was Emanuel Steward, in the midst of the worst month of his Hall-of-Fame career. Just weeks earlier he had stood in the corner watching Prince Nas implode in spectacular fashion. Now his other British import, Lewis, had failed to make the count. It was definitely a “kick them while they are down” moment for Foreman, though Steward would have the last laugh, eventually replacing the big man on many HBO telecasts.

After the bout, Steward dismissed the idea that Lewis was out-of-shape or had been getting worked by journeyman Lamon Brewster in sparring. He compared the bout to a game of pool where an experienced shark relaxes against an easy mark.

“He doesn’t concentrate as hard and he plays around a little,” Steward told The Ring. “Pretty soon he’s playing at their level, not the way he would against another guy who is at his level. Lennox got caught because he was just playing with the guy. End of story.”

In the ring, a jubilant Rahman revealed he had heard all the talk before the bout, quietly going about his business while Lewis focused his attention on Tyson and the super-fight that he’d temporarily scuttled, millions up in smoke with a single blistering right hand.

“No Lennox and Tyson,” he sang as a bemused Merchant looked on, “no Lennox and Tyson.”

Of course, history says otherwise. Lewis would eventually trounce Rahman in a return bout in Las Vegas, returning the favor with a fourth round knockout of his own. The Tyson dream match would soon follow.

Rahman’s entire, ever-so-short reign seemed snakebit. He missed the crowd waiting for him at the airport to celebrate his victory when he decided to take a rental car from New York to Baltimore instead. The next day, during a parade to commemorate his victory, the convertible he was riding in was blind-sided at an intersection, sending his wife to the hospital.

If that wasn’t bad enough, he eventually threw in with the despicable Don King for a signing bonus that included $500,000 stuffed into a duffel bag—then subsequently lost a court battle that ended with the former champion guaranteed an immediate rematch. Finally, he was knocked not just out, but right into the opponent stage of his career by a resurgent Lewis.

Still, he’d always have the one magical day in South Africa (see the fight for yourself here).

“Even if it was for only one night,” Rahman told journalist Steve Bunce years later. “For one night I could say I was the baddest man on the planet. Nobody in the world could beat me. I was the champion, the best fighter on the planet. That’s a special feeling.”

It's fascinating that the big Ls in the career of the great LL are Oliver McCall and the Rock (Merciless Ray Mercer should've been there, too, in a just world), not any all-time greats.