As he stepped into the ring to fight Ray Mercer under the bright lights in Atlantic City, Donald Trump and Marla Maples unmissable on the hard camera, Larry Holmes was supposed to be finished. At 42, he was more than a decade removed from his “greatest” triumph, a sad, anti-climatic victory over a doddering Muhammad Ali to win The Ring Magazine version of the heavyweight championship and officially take his place among the immortals.

Holmes looked every one of his 507 months, paunchy, sporting transition-lens glasses, taking calls during interviews with Sports Illustrated about his many rental and commercial properties in Easton, Pennsylvania. An old man’s problems. A comfortable man’s problems. Mercer, by contrast, was a young 30, a newcomer to the sport who didn’t put on a pair of gloves until well into adulthood, his entire boxing career clocking in at just seven years and change—about the length of time Holmes held heavyweight gold in his prime.

An Olympic Gold medalist, just like the legendary names Holmes attempted to follow in the heavyweight division all those years ago, Mercer had announced himself formally as a contender for the crown with a scintillating knockout of poor Tommy Morrison, trapped in a state of semi-rigor mortis as punch after punch rendered him a forever meme. Against Holmes, Mercer was the betting favorite at odds of up to 4-to-1 at some sports books, clearly being primped and groomed for a shot at glory. And it made sense—despite George Foreman’s recent return to prominence, no one ever mistook boxing for an old man’s sport.

Worse, we’d already seen a version of this story. What was Ray Mercer, after all, other than a bargain-basement Mike Tyson, the young fighter who had sent Holmes back to Easton $2.8 million richer four years prior? For Holmes it was an old-fashioned exchange. His pride was diminished but his bank account grew stouter than ever. Tyson had dropped the bigger man with an overhand right in the fourth round, following up like a jackal who’d just caught the scent of blood, or, as Robert Cassidy wrote in The Ring, “with all the subtlety of a polar bear on acid.”

It was the first and only knockout loss of Holmes’ career, in some ways an ignominious, myth-smashing bout that confirmed to the naysayers what had been whispered throughout his run on top. Holmes, to his critics, sat the throne during a low-point in heavyweight history, ruling over a collection of sad, coked-up nobodies who didn’t measure up to the titans of the 1970s.

That wasn’t entirely fair of course.

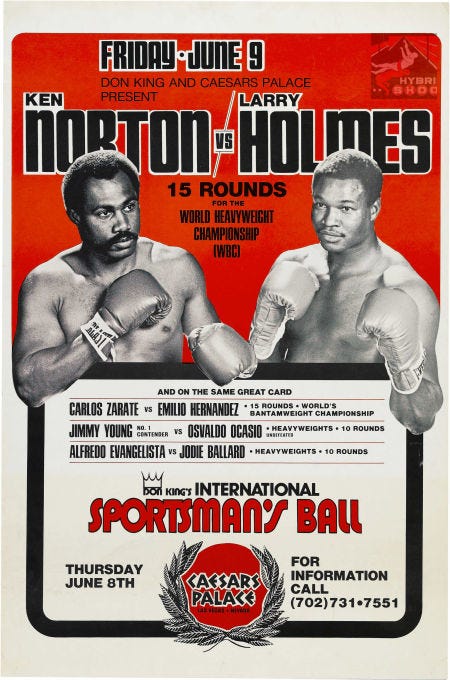

Michael Dokes, Tim Witherspoon, Tony Tubbs and the quirky Michael Spinks have all been boosted somewhat by recent historical revisionism. The twin pillars of Holmes and Tyson bookend the era, neither man requiring an introduction, both generally considered candidates for any top 20 list. Holmes himself was a product of the 70s, even dispatching some of the lesser legends of the time, beating Earnie Shavers in two memorable fights and winning a version of the heavyweight title against Ken Norton at Caesar’s Palace, taking just a fraction of the purse for a chance to prove himself against a leading light.

“I was happy just to get a chance to fight for the title,” Holmes said. “That’s all that mattered. At that time I was thinking about the title and proving I was the best. Not the dollars, nothing else. It was all about the title.”

Unfortunately for Holmes, his time as heavyweight’s top dog wasn’t remembered for fights like the one against Norton, arguably the best heavyweight bout of the modern era. Instead, he began his run bludgeoning the beloved Ali (“No one hated that more than me,” Holmes said), then was showcased in an ugly, racially-tinged fight with white hope Gerry Cooney that felt like an anachronism 45 years after Joe Louis had captured a nation’s heart.

“That fight brought a lot of unattractive people out of the woodwork,” HBO commentator Larry Merchant said. “There was an undeniable racial element that the promoters and the media played up. It was the first time in recent memory that a white fighter posed a serious challenge to the heavyweight title. Black Americans had dominated the sport for twenty years and promoters saw an opportunity.

“Boxing has always been tribal and perhaps this fight brought out a kind of tribalism that had by then become most unspoken. It also brought out the best in Larry. He was highly motivated. Cooney was a good fighter who could really punch. There are fighters from that era he could have beaten. But not Larry. Larry was just too good for him.”

Perhaps because he often made it look so easy, the contenders he dispatched over the years were widely dismissed. There was also the not inconsiderable matter of aesthetics. Foreman and Norton had been musclebound, almost super-human. Ali was physical perfection. Even Joe Frazier exuded danger, his eyes like blinking red lights promising a bad end for anyone foolish enough to tangle with him. Holmes? One writer called him “pear-shaped and spindly legged”, a crushing if apt description of a champion who didn’t quite look the part.

At the time these things bothered him deeply. He’d seen how people fawned over Ali and wanted to taste that kind of love and adoration. Over the years, he’s had time to reckon with it all, realizing a lot of things were out of his control.

“Let’s face it,” he said, “I followed one of the great fighters of all time.”

Despite it all, Holmes thrived. He bought a Rolls Royce, then five. While he didn’t immediately capture the imagination, his dogged workman-like precision at least commanded respect. Then, just as he was on the verge of immortality, challenging Rocky Marciano’s undefeated streak of 49-0, Holmes was beaten in controversial fashion by light heavyweight kingpin Spinks. He could have potentially galvanized fans behind him in the moment, a champion unfairly cast aside—instead, angry and frustrated, he was baited into insulting the Italian saint, claiming the dearly departed icon “couldn’t carry my jockstrap.”

It was a line that had gotten a chuckle when Joe Frazier delivered it to Jimmy Young during a sparring session, Young returning from the locker room with a jock in hand to prove him wrong. Holmes had seen this play out as a young fighter and it stuck with him.

In a different context, it didn’t play nearly so well. For many white fans, already sore about the Cooney demolition, it was an unforgivable sin. Despite Holmes’ attempts to immediately walk it back, it’s too late to close the barn door after the horse has bolted. As Holmes recalls it, by the time he returned home after the bout and the attack on Marciano, the billboard proclaiming Easton the “Home of Larry Holmes” had already been removed.

“I had no issue with Rocky,” Holmes said. “I had his picture on the wall of my gym for years. We are part of an exclusive club. How do you compare fighters from different eras? He was five foot nine and 185 pounds. That’s not even a heavyweight today. Is it even a fair fight?”

Holmes had been everything society claimed it wanted from a champion. He was responsible, faithful to his family, free from scandal and controversy—traits people supposedly want to see from athletes while secretly hoping for a train wreck.

“Larry Holmes is the heavyweight champion who lives next door,” Leigh Montville wrote in the Boston Globe. “He might have all the qualities all the polls say people want from their heroes…but he still lives next door. There is little romance to be found next door.”

Holmes was also crabby, proud and occasionally outspoken about the nature of boxing and the nation. He was a capitalist, always crystal clear that he was fighting for money above all else. “Bidness” as he called it, something that didn’t always resonate with fans who wanted to romanticize the sweet science. Sports Illustrated’s Richard Hoffer called him “petulant” in a profile that was denied the cover by a hockey player of all things, an opinion that appeared fairly unanimous among contemporaries. Reporters liked the private Holmes, the one who’d talk openly with them about behind-the-scenes wrangling at his gym or hotel suite. His public persona was less lovable, something the media occasionally had to point out—and Holmes didn’t enjoy critical articles from people he’d taken into his confidence.

After years in the spotlight, he and the press both appeared exhausted of one another. So too his relationships with promoter Don King and various television executives. No one, it seemed, was especially glum to see Holmes fade into obscurity. His last words to the public in 1986 after a second loss to Spinks were to the point, crude and hilarious despite the sadness in his eyes. Cornered by Merchant in his dressing room after bailing out on a post-fight interview, Holmes told the world exactly what was on his mind.

“I can say to the judges, the referees, the promoters to kiss where the the sun don’t shine,” he said. “And, since we’re on HBO, that’s my big, black behind.”

As much as many were ready to move on, including Holmes in the moment, boxing wasn’t quite through with Larry. The wrestler Ric Flair, champion in his own right throughout the Holmes’ era, used to say “To be the man, you’ve got to beat the man.” Tyson, for all his fame and fortune, hadn’t; because of the controversial nature of the Spinks losses, Holmes still lingered. Even as “Iron Mike” began his ascent to stardom, mostly creaming guys Larry had already beaten, there was the feeling of unfinished business.

But the result in 1988 was fairly definitive—with his knockout win, Tyson had seemingly closed the door on the 70’s once and for all. He’d crushed Holmes, then annihilated his conqueror Spinks in just 91 seconds. Tyson was the avatar of a new generation, capturing the energy and enthusiasm of the burgeoning hip hop culture and distilling it into crouching, snarling, visceral violence.

As the country would later learn, however, Baby Boomers were hard to keep down. George Foreman had opened the door back up with his own comeback, smiling that dead-eyed smile, cooking burgers and bums in equal number as he knocked off fighter after forgettable fighter. Holmes, who kept one eye on his former profession, remembers telling a friend on a fishing trip the new crop of heavyweights “can’t fight worth a damn” and proceeded to go about proving it.

Heading into the Mercer tilt, Holmes was five fights deep into his own return, one Hoffer believed didn’t reek of selling out quite like the Tyson cash grab had:

This second comeback seems different. Neither money nor the boredom of retirement explains it entirely. There is pride. Those two losses to Spinks haunted him in retirement more than anybody thought.

…By all accounts, the idea of regaining the heavyweight title was just not there at first. But with Spinks unavailable and Tyson in prison, Holmes became ambitious. After all, look what George Foreman, several tons past his glory years, had done in his comeback. Why not a title fight?

(Promoter Bob) Arum proclaimed the whole idea a "joke." Then he noticed the ratings Holmes was getting on cable's USA Network. Holmes was laboring through decisions against stiffs, and still the people tuned in.

Holmes, forever a mercenary, was suddenly serious about regaining past glory. Arum, smelling money, was happy to play along, booking the Mercer fight for a potential shot at Evander Holyfield’s title. The media and fans were skeptical at first. In the Daily News Hall-of-Fame cartoonist Bill Gallo dubbed him “Old Folk Holmes” and most of the boxing press met the fight firmly locked in their default setting—cynical.

“It’s always been that way,” Holmes told the Philadelphia Daily News. “I’ve never gotten my just due. Or my respect.”

But Foreman’s sustained success, even against Holyfield, made the endeavor seem possible if not probable. After losing a $100 million fight with Mike Tyson, the establishment needed to make money wherever it was to be found with Holyfield. Even if Holmes wasn’t a real contender, he was a recognizable name. That put him, in the mind of decision-makers, ahead of relative unknowns like Lennox Lewis and Riddick Bowe.

No one knew he’d walked into his training center in Jacksonville, Florida and asked trainer Cliff Ransom to turn the lights on. They were shining bright. The old man, already facing an up-hill battle, had a detached retina. A doctor told him to call the fight off. Instead, he swore his tight circle to secrecy, afraid there was no time for a second chance if he was forced to pull out of the bout.

Although nothing quite on the level of a secret injury, Mercer had stuffed a career’s worth of drama into his 18 fights as well. He went to war with Bert Cooper, pushing himself to depths he was open about never wanting to reach down for again, then secured victory in the face of certain defeat, coming back to bust Francisco Damiani’s hopes (and his nose) in a fight Mercer was behind in on the scorecards.

“Every fighter dreams of having that one punch knockout that he pretty desperately needed,” Mercer said. “I got mine.”

It was a clever bit of promotion, turning life-and-death struggles with journeymen into personal victories instead of concerning displays of weakness. Of course, Mercer, like all undefeated sluggers, sold himself with the dynamite in his fists, assets that overcame many perceived issues. It took a team effort to sell Holmes at this point though. Even his opponents got in on the act, with Mercer expressing his admiration for the long-time champ and everyone involved careful to never hint that the fight might be anything less than competitive.

“Larry may still have his great jab and his knowledge makes him more of a threat than anything, but I doubt if he will be able to put that experience to use,” Mercer’s trainer Hank Johnson told the press.

Johnson had been with the rising star since his Army days, completing a 20-year career as a combat medic in the service before transitioning to the professional ranks where he continued as a mentor to Mercer. He didn’t buy into the press’ critiques of the fight being little more than a joke or the idea that Holmes would be overmatched. But he was convinced youth would overpower experience, the young lion conquering the faded star.

“I think he still has that gleam in his eye, that determination to win, but that’s not enough. We all have to accept the fact that when Father Time gets on your back, he doesn’t get off,” Johnson continued. “It’s not everyday you get to fight a legend; it’s not every day you get to put one out to pasture.”

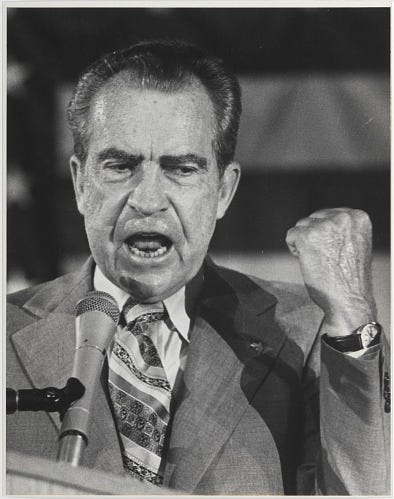

Mercer was just entering his prime. Holmes? He’d started his professional career in the Nixon administration. Despite the long odds, Mike Dessart of HBO’s pay-per-view arm TVKO was hopeful the event would draw over 300,000 pay-per-view buys, topping Mercer’s performance against Morrison. It ended up close, scoring a reported 250,000 paying customers for a 1.3 percent buy rate. But the real reward for the winner was not mere cash—it was opportunity. Holyfield loomed for the victor, the title shot still serving as heavyweight boxing’s ultimate spoil.

“The winner of this fight stands to make $10 million to $20 million this year,” Mercer’s manager Jack Dell said at the time. “The consequences are spectacularly serious.”

Holmes was greeted by the crowd with a combination of indifference and boos. Early on, the negative nellies in the press looked prescient for once. Mercer wobbled Holmes with a hard jab and looked intent on ending the night early. After initially preparing for a 12-round battle, his team had shifted to a new strategy in the final month of training. He wanted to end it and end it early. He gave it his best shot. When that didn’t happen, he was lost.

Holmes never looked particularly fazed after those early, questionable moments, and the old warhorse settled into a routine that differed significantly from his modus operandi during his peak. He’d back into the ropes, resting those skinny legs, all but begging Mercer to come forward. Once he did, that famous Holmes hammer would bang off the younger man’s dome, Mercer’s furious response mostly dodged or deflected. Then the return fire would come, blows scoring with a frightening accuracy. At one point Holmes had landed over seventy percent of his punches, the fight that had seemed to be his to lose suddenly right there to win.

By the middle of the fight, Holmes was comfortable enough to have some fun in the ring. He was shaking his booty at times and reaching out his big left hand and placing it on his foe’s forehead to hold Mercer back like he was his big brother. “Having the time of his life,” Mercer said, making it clear it wasn’t a good thing to be on the wrong side of that kind of fight.

“It was kind of weird,” Mercer told The Ring in 2022, able to see the funny side of things with some distance. “I was trying to beat him with everything I had. I got psyched out; he was holding the ropes, trying to throw a jab and talking to his wife in the audience. If it hadn’t been for his wife, I’d have beaten him.”

In the sixth round, as Mercer ineffectually wailed away on the ropes, Holmes looked directly at the camera and the world, delivering concise, cutting commentary of his own.

“I’m not,” he said incredulously, “Tommy Morrison.”

By the ninth round the impossible was happening—the fans had embraced the prickly former champion, holding him in their arms, all forgiven. Time, as they say, heals all wounds. Finally, as Michael Katz wrote in the Daily News, he was getting his flowers:

The waves of “Lar-ry, Lar-ry” finally arrived yesterday morning on the Boardwalk and Larry Holmes, one of the most underappreciated heavyweight champions in history, could finally bathe in glory.

Holmes seemed grateful in the moment but had also been around the block more than a couple of times. He knew the love of the masses was fleeting. Holmes being Holmes said as much in the post-fight interview after winning a decision (117–112, 117–111 and 115–113).

“I love this,” he admitted to announcer Joel Goossen. “But now there’s going to be somebody who says ‘Ray Mercer wasn’t nothin.’ Because they don’t want to give me the credit I truly deserve.”

He wasn’t wrong. In the months leading up to his eventual bout with Holyfield, the critics were out in force, repeating the same old stuff that preceded the Mercer fight. Nothing, however, could take away from this moment—a final, glorious win for one of the greatest to ever strap on a pair of gloves.

After keeping things close for a time against Holyfield, Holmes ultimately lost a wide decision, throwing up in his corner immediately following the final bell. The fight was widely panned, with Sports Illustrated proclaiming “somewhere Jack Dempsey, Joe Louis and Rocky Marciano were screaming.” Only later would we come to appreciate all Evander had done—something that no doubt felt familiar to Holmes. All said and done, Larry could still smile. What would he do differently against Holyfield?

“I would’ve fought him in 1980.”

Jonathan Snowden is a long-time combat sports journalist. His books include Total MMA, Shooters and Shamrock: The World’s Most Dangerous Man. His work has appeared in USA Today, Bleacher Report, Fox Sports and The Ringer. Subscribe to this newsletter to keep up with his latest work.

Excellent stuff. Late-career Holmes deserves respect on his name, and Mercer was no slouch. That was one of the first fights I remember caring about, even if the narrative was always “the division is dead” (when aren’t divisions of heavies dead, in any sport aside from sumo?)

Foreman’s ’dead-eyed smile’ is exactly right.