Los Angeles. A city of angels with dirty faces. A sun-bleached postcard hiding a million grubby secrets. It’s a town that sells you the dream, takes you to a scenic overlook, then picks your pocket while you’re looking at the stars. It’s a beautiful lie, told over and over until it feels like the truth.

In that way, it was the perfect place for UFC 60.

They called it "human cock-fighting," a "wild barroom brawl" for the cheap seats. For years, the sport was an outlaw mudshow, chased from the mainstream by politicians who saw a dirty business. It was banned, pushed underground, too brutal for the bright lights of a place like California.

Then the promoters got wise. They put on a suit and tie, got in a room with the regulators, and came out with a clean story: the "Unified Rules of Mixed Martial Arts Combat." It was just enough lipstick on the pig.

The California State Athletic Commission, smelling money, bought the grift. They lifted the ban. The commission boss, Armando Garcia, promised to make it "acceptable," knowing that "the way California goes... is the way the sport is going to go." The door to the big time, to Los Angeles and beyond, was finally unlocked.

The bloodsport was ready for its close-up.

The night of May 27, 2006, the fight game came to the Staples Center for the first time, UFC bringing the bread and the circus to a city of vampires always looking to renew itself with the blood of the young. It was a spectacle, a happening. The beautiful people were there, their teeth as white as their consciences were gray. The Rock. Cindy Crawford. Paris Hilton. Even Ari from Entourage was spotted. It was a happening.

Access Hollywood, Entertainment Tonight, Extra—the whole damn town was there to see a fight. They were there for the legend, for the story. The pretty one. The one they put on the posters and billboards.

But this is L.A. And in L.A., every story has an underbelly. A grimy, greasy, ugly truth that you don’t see until you get up close and the light hits it just right. This fight, these fighters, the men who owned the cage they bled in—they were all pure Los Angeles. A shiny facade, and right beneath it, something else. Something dirty.

A specter lingered over the UFC, haunting every champion who tried to follow his warrior’s path. He’d disappeared when the politicians came, the law cracked down, the novelty checks got smaller.

The ghost had a name: Royce Gracie. This new version of the fight game all started with him and he lingered more than a decade after he’d last entered the cage.

His is a family story. A patriarch name Hélio. A founding father. The story he sold you was a good one. A frail, 140-pound kid who couldn’t climb a flight of stairs without fainting, who watched his brothers train in the Japanese art of judo and saw a flaw. He saw a system built for the strong. So he tinkered. He played with the physics of it, the cold mechanics of leverage. He built a new art from the bones of the old one, a system for the weak to conquer the strong. He called it Gracie Jiu-Jitsu, and it shook the world.

A beautiful story.

A lie.

The underbelly was uglier. Gracie Jiu-Jitsu wasn’t an invention. It was a rebranding. A marketing gimmick. It was judo, plain and simple, a martial art that had been around for decades. Hélio didn’t invent it. He didn’t even start it. His older brother, Carlos, was the real beginning. Carlos was the one who learned from the Japanese master, the one who opened the first academy. Another brother, George, was the real fighter, the family champion who stepped into the ring time and again while Hélio was still building his own legend. But Carlos was the visionary, the one who made it more cult than sport.

And Hélio… well, Hélio was just better at marketing. He was the face of the brand. He and Carlos built a dynasty, a quasi-religion with its own diet and its own dogma, all designed to sell one thing: the supremacy of their name. They were brilliant. They were pioneers. They were supposedly undefeated, though the old and withering newspapers said otherwise.

They were selling a product built on a big lie.

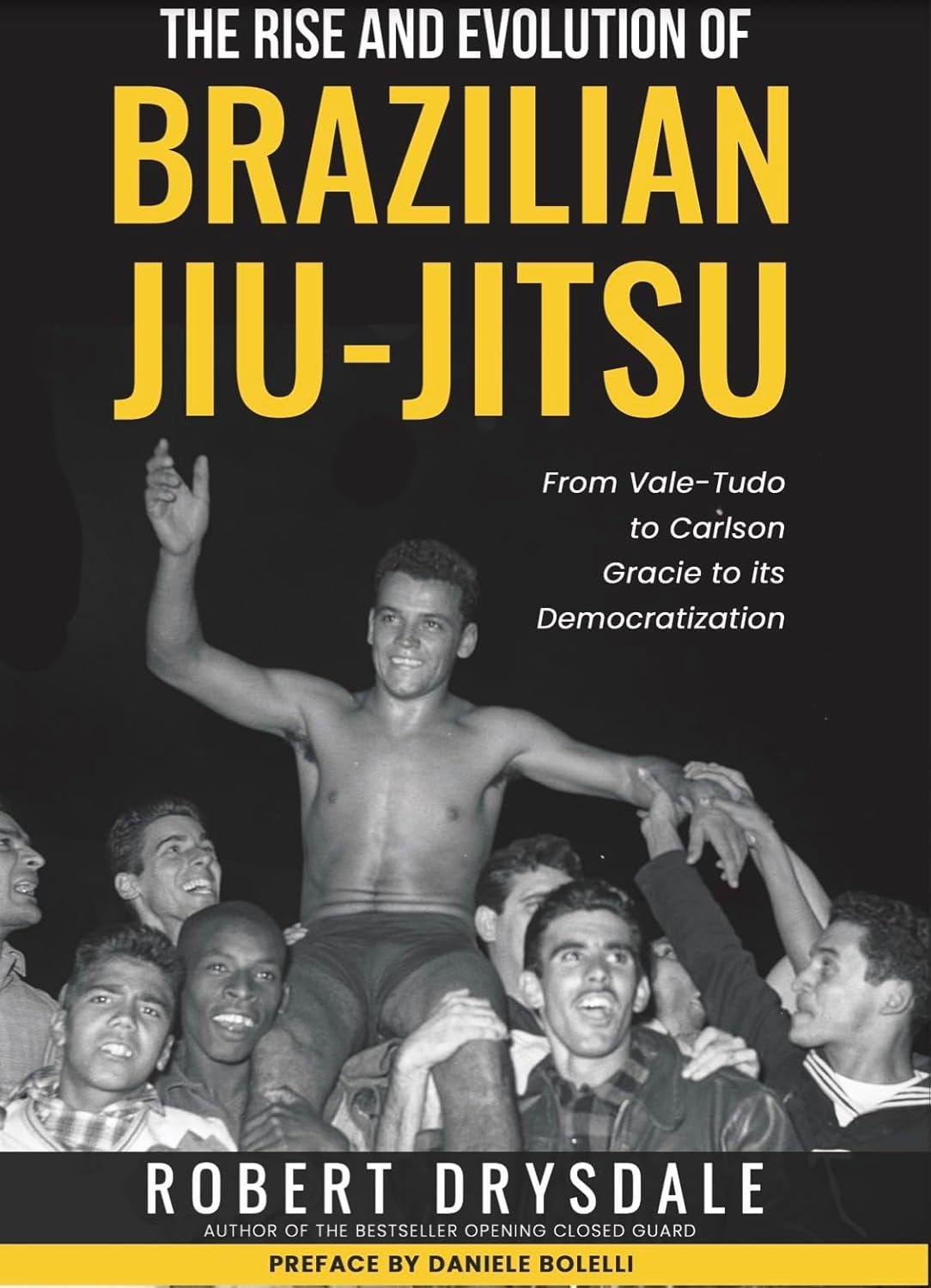

“It is obvious,” historian Robert Drysdale writes, “that the Gracie brothers didn’t invent anything.”

Royce was the sequel. The living proof. Rorion, Hélio’s eldest, cooked up the Ultimate Fighting Championship as the ultimate sales pitch, the Gracie Challenge on a global stage. He didn’t pick the family’s best fighter, his brother Rickson, a man who was all muscle and menace. No, he picked Royce. Skinny, unassuming Royce. Because if a guy who looked like he could barely win a thumb war could choke out a gallery of monsters, then the art itself must be magic.

And it worked. Royce became a legend. They sold him as the unconquerable champion, the underdog who tamed the giants. They plastered his record everywhere, even ahead of this fight, his triumphant return: undefeated. But there was always an asterisk, one you couldn’t see unless you looked close. “Inside the octagon.” It was a con man’s phrase, a way to erase the inconvenient truths. The losses he took outside that cage didn’t count. The loss in Japan to Kazushi Sakuraba—a 90-minute beating that ended when his own family threw in the towel—that was just a bad dream. They even bent the rules for him in that fight, and he still lost.

And was he ever really an underdog? When you really stop to think about it? In those early UFCs, he was the only man in the building who knew the game. He was a shark in a wading pool.

“Originally you have guys that understand what is going on against guys with one boxing glove who had no clue as to what was going on,” announcer and podcaster Joe Rogan said. “That’s what we had with Royce Gracie in the early UFC’s.”

It’s easy to look like a genius when you’re the only one who’s read the book or even understands the language. Once the world caught up, once the other fighters learned how to swim, the shark looked a lot more like a goldfish. The magic was gone. All that was left was the myth.

And a myth is just a lie that people want to believe.

The other corner had the machine. Matt Hughes. On the surface, he was everything early UFC bad boys like Tank Abbott weren’t. He was the new American dream. A farm boy from Hillsboro, Illinois. Corn-fed, clean-cut, a two-time All-American wrestler with a college education. He was the perfect poster boy for the new UFC, a promotion desperate to wash the grime of its early days off its hands and look respectable.

He was humble. He was hardworking. He smiled for the cameras.

Another beautiful lie.

You peel back the layers on Matt Hughes, and you find something else. Something hard and mean. Violence brewed in that kid. He grew up fighting his twin brother, Mark, two bulls in the same pen. He got into fights at school. He got into fights at parties. He was a bully, a trait that followed him right into the gym and the cage. He’d taunt opponents. He’d haze the new guys on The Ultimate Fighter, the reality show that was supposed to make him a star. He once met a fighter he’d beaten, Joe Riggs, and his wife, and his idea of a friendly hello was a sneer and a joke about the beating he’d given her husband.

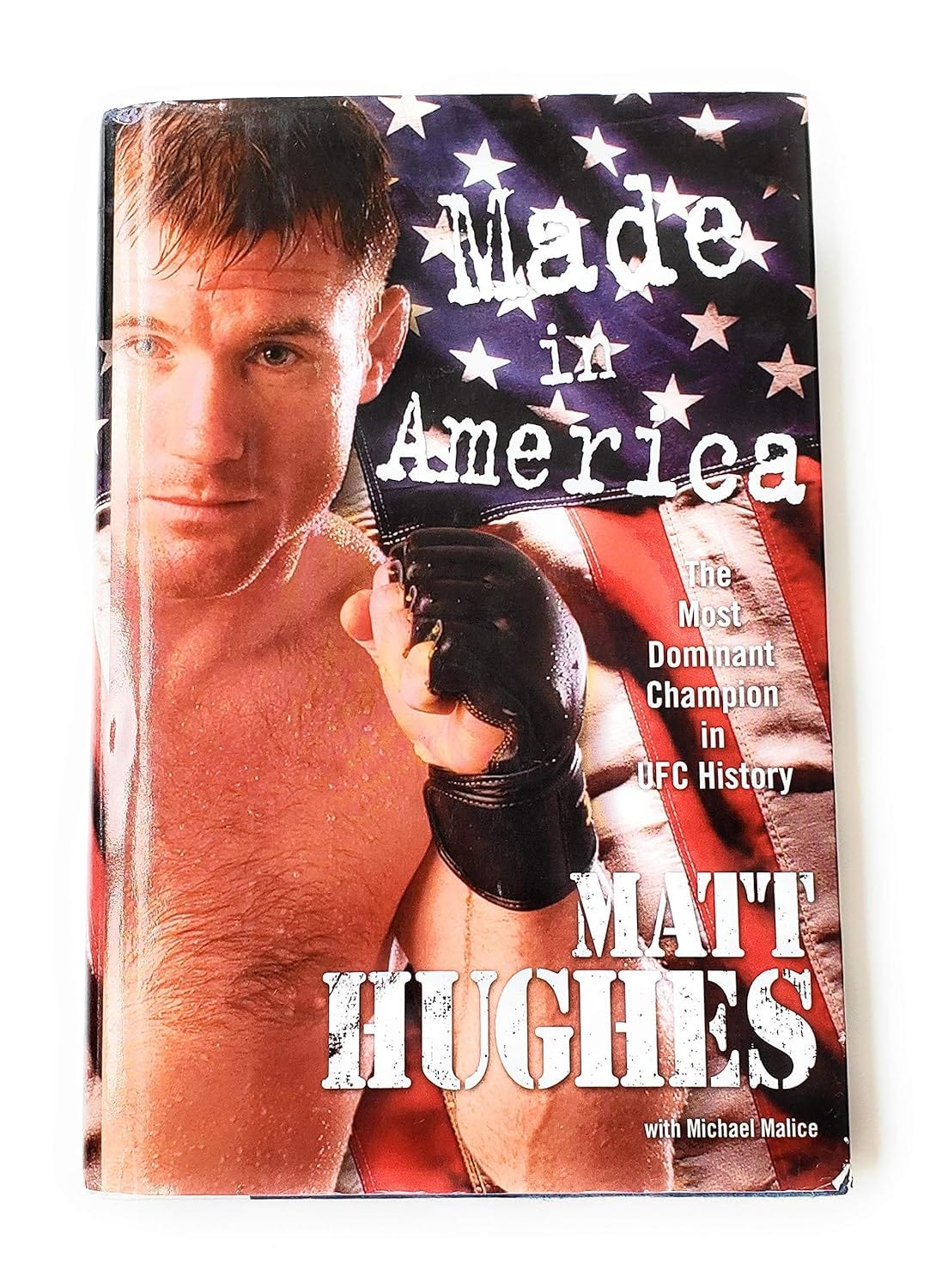

The Hughes lie was exposed by the man himself, right there in the pages of his absolutely insane autobiography. Every page is a new indictment, told with a straight face and a clear conscience. It’s almost shocking, even for people in the fight game.

“I just bought a copy of Matt Hughes book, and am in 3 chapters already. It is borderline unbelievable,” fellow UFC fighter Sean McCorkle wrote in his seminal running review of this literary gem. “..As astounding as some of this sounds, everything I post is actually in the book.”

It’s a masterpiece of accidental self-incrimination, a portrait of a man with a chip on his shoulder so big it casts a shadow over everything he touches. He sets out to write his own legend and ends up penning the perfect character study of a heel. He’s the villain in his own story, the last guy in the room to get the joke.

The all-American smile was a mask. Underneath it was a snarl. He wasn’t a hero. He was just a different kind of animal, one that Zuffa, the new owners of the UFC, could package and sell to the masses.

The Miletich Fighting Systems gym wasn’t a health spa, though they did sometimes train on a racquet ball court; it was a factory in the grimy heart of Bettendorf, Iowa, a place where freight trains rattled the windows and the Mississippi swallowed the rust from the factories. Pat Miletich, a man who learned about life from bullies and bar fights, was the foreman, and the sign on his door promised beatings around the clock. It wasn’t a joke. It was a cauldron of sweat, spit, and bad intentions, a place where men came to get broken and remade in Miletich’s own image.

The rules were simple and mostly unwritten: you didn’t pay at the door, you paid in blood on the mat. You pushed your brother until he bled, and then you helped him up. And you never, ever, fought another man from the house. It was a tribe forged in a glorified warehouse they built with their own hands, a blue-collar brotherhood of killers in a world that didn’t want them.

Into this house of pain walked Hughes, the farm boy, eventually Miletich’s prize pig. He had the strength of the soil in his hands and a champion’s pedigree, and Miletich took him in, made him his protégé, and built him into a killer. But the loyalty was a one-way street. While the gym ran on a code of brotherhood, Hughes ran on ambition. Other fighters saw him as a cancer, a man who "treated people like shit" and had "no respect." The whispers turned to shouts when he finally walked, a year after this fight, taking another fighter with him and leaving a hole in the family Miletich had built. It was the ultimate betrayal, proving that the sharpest knife is sometimes wielded by the man you call brother.

That’s a story for another time.

In 2006, Matt Hughes wasn't a star, at least outside the sport’s hardcore fanbase. Not yet. He was a black hole where title aspirations went to die. He took the welterweight strap from Carlos Newton in a beautiful, ugly mess—a double knockout where he was the first man to regain consciousness, a perfect piece of cage noir. Then came the reign. Five straight defenses, a meat-grinder of a run that left a trail of broken men like Frank Trigg and Sean Sherk in its wake. He didn't win with flash; he won by making the other guy quit living for fifteen minutes.

A subset of fans didn't love him. They called him a bland wrestler online and his pay-per-view events didn’t sell. But he wasn't there to be loved. He was there to collect his paycheck and another man's pride.

Hughes was the perfect champion for in some ways, just waiting for his signature win: dominant and efficient, with a darkness they could market as intensity. He was the American heartland’s answer to the mystical Brazilian, a hammer built to shatter a myth.

And then there was the house. The men who owned the cage, the lights, the fighters, the whole damn show. The Zuffa-led UFC. The story they told was that they were the sport’s saviors. They were the shiny young executives who rode in on a white horse to rescue the sport from itself. They were the ones who cleaned it up, who ran toward regulation, who made it safe and palatable for the masses.

It was their greatest marketing pitch. Their biggest lie.

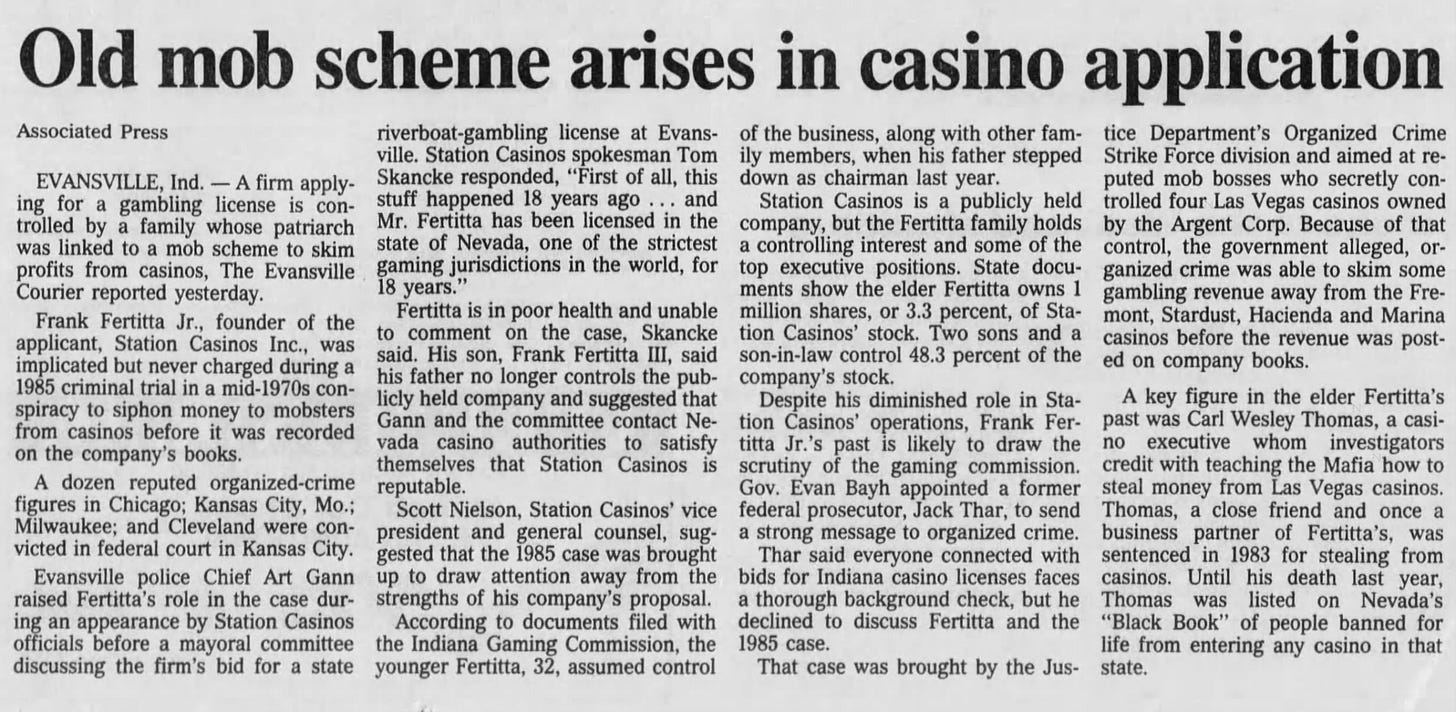

The truth was, the old owners, a company called SEG, were the ones who started to make changes. They were the ones desperate for regulation, desperate for legitimacy. They were bleeding money, getting chased out of states by politicians like John McCain, who called their product “human cockfighting.” They went to the Nevada State Athletic Commission in 1999, begging for a rulebook, for a stamp of approval that would save their company.

And who was sitting on that commission? A young, ambitious casino heir named Lorenzo Fertitta. He and the commission denied SEG. They kept them in the regulatory darkness. Then, in 2001, Lorenzo and his brother Frank III bought the UFC. They bought the whole broken-down circus for a song—just $2 million. It was a fire sale. A few months after the Fertittas took over, the Nevada commission, Lorenzo’s old stomping ground, miraculously reversed course and sanctioned mixed martial arts. It was a beautiful piece of business. Cynical. Brutal. Pure Las Vegas.

The Fertitta brothers were the picture of the new corporate guard. Young, handsome, college-educated. They looked clean. But you don’t get that rich in Vegas without getting your hands dirty. Their family tree had some interesting branches, ones that led back to the Galveston crime syndicate, the Maceo organization. Their father, Frank Jr., had been investigated for skimming operations at the Fremont casino in the 70s, a classic mob racket. He was cleared, of course. They always are. But the smell lingers. The money gets washed, but you can never get the stain all the way out. The Fertittas weren’t just casino guys. They were a generation removed from the real thing.

They understood how the world really worked.

They sold you a story about two Vegas knights in shining armor, the Fertitta brothers, who rode in to save the fight game from the gutter. They were the heroes, the saviors, the smart money that legitimized a bloodsport with a pitbull named Dana White running point. It was a beautiful story, the kind they tell in boardrooms and business schools.

The truth was a grimy back-alley shiv.

Lorenzo watched the old owners, SEG, bleed out, denying them the sanctioning they needed to survive. When the company was a corpse, they picked its pockets and built an empire on the blood and broken bones of fighters they starved, keeping the talent on short leashes and paying them a pittance of the revenue, a tactic so brutal it sparked a massive class-action lawsuit alleging they ran an illegal monopoly to suppress wages. They squeezed every dime out of the men in the cage, then sold the operation for $4 billion, walking away with pockets full of cash while the fighters who made them rich were left to count their scars. It was the greatest grift in sports, all done with a smile and a press release about how they saved the very thing they’d bled dry.

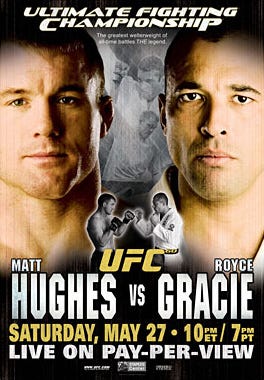

Which brings us back to the cage at the Staples Center. The fight itself was the biggest lie of all. The posters sold it as a superfight, a clash of titans. The original superstar, Royce Gracie, undefeated in the octagon, against the most dominant champion of the new era, Matt Hughes. A pick’em fight. A battle for the ages.

In reality, it was a human sacrifice.

It was a public execution disguised as a sporting event. Royce Gracie was 39 years old, a man living off the fumes of a legend his promoters had carefully manufactured. He hadn’t evolved. The game had passed him by. Matt Hughes was a 32-year-old champion at the absolute peak of his powers, a wrestling machine who had spent years in a gym with killers, deconstructing the very art the Gracies claimed was perfect.

Royce had no chance. It was bloodsport at its most cynical. This wasn’t a contest; it was a coronation. Zuffa needed to kill the ghost of the old UFC to legitimize the new one. They needed their machine to dismantle the myth, piece by piece, in front of 600,000 paying customers on pay-per-view.

The fight game is a con, and for UFC 60, the con was beautiful. They told you Royce Gracie was the "original conqueror," undefeated, a perfect 11-0 inside their Octagon. It was a convenient fiction that wiped the slate clean—the 90-minute beating he took from Sakuraba in Japan, the draw with Shamrock, the other times the magic trick didn't work—all of it vanished into the promotional ether. They weren't selling a fight; they were selling a myth, inflating a legend just so their new machine, Hughes, could be the one to kill it.

“I’m not just a part of the history,” Gracie said before the fight. “I am the history. This is my House. I built it…I’m going to choke him out. Apply a submission hold. Make him quit, help him up; send him home.”

And the people believed. Money flowed into casinos for Gracie, whether because of ignorance or nostalgia is anyone’s guess. The smart money knew the score, but the hype was so thick you could cut it with a knife, and the betting lines were nearly even.

“It was definitely the subject of the greatest TV commercials and hype in the history of the company. It stirred the emotions,” reporter Dave Meltzer wrote. “Those who really didn't understand how the game had changed were sure Gracie would win.”

Despite the hype job, it was never going to be an epic contest. It was a coronation, a one-sided beating dressed up for pay-per-view, and the house knew exactly how it was going to end before the first bell ever rang.

“The legend,” announcer Mike Goldberg exclaimed, “has returned.”

The fight, however, was a formality, a four-minute mugging under the bright lights. Gracie came out throwing lazy kicks. Hughes walked through them, grabbed him, and slammed him against the fence. In that first clinch, the whole story was written. Hughes said later he could feel it instantly: the ghost was weak. He was just an old man in a young man’s game.

Hughes took him to the ground, to the place they called the Gracie ocean. He waited for the magic trick, the secret submission that was supposed to end the fight. It never came. There was no magic left. Hughes moved to an armbar. He felt the arm strain, ready to pop. But Royce, ever the proud warrior, wouldn’t tap. He would have let Hughes snap his arm in two before he’d give in.

But Hughes was a machine, and machines are efficient. He wasn’t there for drama. He was there to do a job. He let the arm go, took Gracie’s back, and started raining down punches. Hard, thudding, unsentimental shots. One, two, three. The ghost didn’t even try to defend himself. He just lay there and took it, laid there until Big John McCarthy stopped the fight.

It was over. The myth was dead. American wrestling, as Hughes put it, had beaten Brazilian jiu-jitsu.

The crowd roared. The celebrities smiled. Backstage, the champagne corks popped. The new king was crowned. The house had won.

This is Los Angeles. The sun shines, the money flows, and the beautiful people clap for the beautiful lies. But when the lights go down and the crowd goes home, all that’s left is the blood on the canvas and the grime underneath. The story is never what it seems. Not in this town. Not in this sport.

Here’s the rub, the punchline to the whole dirty joke. The machine dismantled the ghost, sure, a clean kill under the klieg lights. But he didn’t do it with just farm-boy strength and wrestling. He did it with their own black magic. He took Gracie to the ground, into the family’s private ocean, and went for a straight armbar—a classic piece of their own handiwork, then the rear mount, a move straight from their playbook. He was playing their game, using their deck, and dealing from the top. The Gracie name lost that night, no doubt. The myth of the unbeatable man in the pajamas went up in smoke. But the art? The art won. It had escaped the family vault. It was no longer a secret whispered in a private dojo; it was the lingua franca of the cage, a necessary weapon in every fighter’s arsenal.

The family lost their monopoly, but their system had conquered the world.

Jonathan Snowden is a long-time combat sports journalist. His books include Total MMA, Shooters and Shamrock: The World’s Most Dangerous Man. His work has appeared in USA Today, Bleacher Report, Fox Sports and The Ringer. Subscribe to this newsletter to keep up with his latest work.

Great read! I remember the build up to this fight and knowing good and well it was a setup to put over Hughes (who I couldn't stand), but I held a shred of nonsensical hope that Royce had one last magic trick up his sleeve. I knew it was nonsense, but I bought the PPV just the same and felt that rush of adrenaline as the bell rang. I miss those days.

This was great. I still remember watching the commercials and promos and even the "this is my house! I built it!" only for him to immediately (immediately!!) get ragdolled and crushed as everyone knew he would.